Published December 27, 2022

She Has Her Mother’s Eyes: An Interview With Kim Garcia

Kim Garcia (b. 1989. San Diego, CA) is an artist working in sculpture, drawing, and painting. Her practice explores social dynamics and residual trauma from interpersonal relationships, community structures, and memory. Kim comes from a background in creating collaborative community projects that often employ alternative spaces to explore studio art practices, site-specific collaboration, and museum and exhibition research. She is the founder of The Cold Read, an online critique group and artist collective that engages gestures of care and support through writing. And is one of the co-founders of after hours gallery, an art gallery in Los Angeles that hosts seasonal two-person exhibitions. She has most recently shown her work at Phase Gallery, Peripheral Space, DXIX Projects, Human Resources, DAC Gallery, Torrance Art Museum, CICA Museum (Korea), and Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Kim is based in Los Angeles and received her BA from UC San Diego and her MFA from UC Irvine.

How did you first come into art making? What are some of your first memories of art?

KG: I feel like it's always around in the beginning with most artists, right? I went to an elementary school with a fine arts focus, which opened my world to everything being viewed through art. I didn't know what I wanted to do. I knew that I wanted to go into some type of creative field and even thought, at one point, I would be a hairdresser. I just started taking community college classes. Many of the professors came from the University of California San Diego, which had a big emphasis on Allan Kaprow. My beginning experiences with contemporary art came from these artists who studied under Kaprow and were focused on performance, community-oriented works, and a lot of collaboration.

The first piece I made where I was like, "Yeah, I'm gonna be an artist," was probably in 2010, and my work back then looked like portable architecture. I also went through this museum studies program, so I was really interested in display and curation. Marcel Duchamp's surrealist exhibitions greatly influenced my practice, where I was making these collaborative and strange mobile artist residencies and galleries.

When I think about my practice now, it's really about understanding these relationships between communities and any relational structure connected to me. The type of work that informed my practice in the past exists as its own endeavor running alongside my studio practice.

You’ve written about the collaborative component of your work both in your individual practice and then working with other people and trying to locate the “tether” between those two. How do you view collaboration in your work now?

KG: I think maybe it's shifting towards different communities now. But it's always been about creating these generative areas and then being inspired by the group and the relationships of support. In some ways, I am just really investigating levels of intimacy. And now, in my practice, I'm shifting into thinking about my family. There's a natural progression into thinking about chosen family and then returning to the roots of the family. In my practice, it feels important to confront my roots and understand the types of chosen families I interact with.

What are some of the questions you are considering as you're making work?

KG: I think the overarching aim or goal is to focus on things that are not visible but leave behind a record in the body. Often, these types of histories are not recorded in written language or have a definitive account. And I'm not trying to speak for or sum up these unrecorded stories; more so, I am interested in dealing with their complicated layers and reimagining different ways to inscribe a history. I'm trying to give a little bit of power to that – especially in the case of erased histories.

Once I've narrowed down the topic for work, I view the series as a kind of choreography of sculptures and drawings retelling tangential stories woven into a larger narrative. I view my process as a kind of dance, and I attempt to record the stories in my sculptures as a series of physical poses or prompts: How can I manipulate a material to feel stressed, uncertain, or precarious? What does strength look like, and how can all these conflicting feelings combine?

The she haunts series explores your personal folklore through stories passed down from your mother and aims to investigate how narrative has the capacity to transform trauma into power. How did the series come to be and where are you with it now?

KG: I've been working on this series since 2019, but I'm hoping to finally realize the project in my upcoming show in April 2023 at Phase Gallery in Los Angeles, where I can see the works interact in a gallery space.

In my overarching practice, I think about sculpture as a kind of fiction; its potential rooted in a lived experience, one that pulls from reality but gets misconstrued with some imaginary elements. These fictions end up being something like a dream; exaggerated moments of processed lived experiences. And so naturally, I created these fictional prompts to catalyze each series. I had always wanted to make a work about my family dynamic but didn't know where to start. But then I remembered a family folklore my mother told me as a child, and I've been trying to figure out the best way of making work about my relationship to my family without being too literal.

My brother and I used to be teased for having ears that stuck out, and my mother used to tell us this folklore that we have these ears because we're descendants of fairies. I was interested in that narrative being linked to empowerment and this thing that's inherited. But the more I researched into it and asked her to recall the stories, little details would change each time it was recited. It was challenging to get all the stories straight. This struggle has shifted the series into a more complicated narrative. It's almost like she was performing that story in real time based on whatever lingering feeling she had that was attached to the past. I saw her stories as almost like an origin tale of her relationship with her family. At the same time, it felt like a vehicle for processing trauma within multiple levels: our mother-daughter relationship, her relationship with her family, and the history of the Philippines.

To give context, Spain published Catálogo alfabético de apellidos in 1849, which helped establish a governing system that lists last names you could pick from. And the native Filipinos just went through, A through Z, and chose a surname. I looked through the document, and there was no Fumar, which is my mother’s maiden name. I'm sure it was just a name that deviated slightly from its origin, but it's strange because the translation is "to smoke."

The operation of smoke and the surname mirrors the narrative of my mother's story, frequently changing shape. The name in itself is kind of like the whole story; how it's changed, adopted, and reconfigured for a sense of strength, yet still having a bit of trauma in it. That's where the series is now—investigating what is inherited and then this contradiction of power and wounds. With the show I'm building, I'm making these sculptures and wall pieces that will be like an apparition of a guardian or ancestor telling a layered story of my family's past relationships.

I love the act of creation in parallel here. How does your mother see herself within the work? Does she see herself as a collaborator? And what is her response to the series?

KG: I don’t necessarily think my mother views herself as an active collaborator in the work. Moreso, I think she views the work as my version of the inherited tale that processes our collective family histories. In some ways, it has been an excuse to hang out with her, archive her memoir, and understand and deepen our relationship through visuals and materials.

Can you walk me through your making process? You're documenting these oral histories with your mother…are you recording her speaking? How does that conversation then become an object that you make in the studio?

KG: So we tried a few things; we tried writing, which was okay. But there's a lot of editing that happens when she's writing. So we did audio recordings, and I tried to retain as much information as possible by actively listening. Typically, I would make a series of drawings inspired by what I remembered from our interaction. Then I would relisten to the audio recordings, make another set of drawings, and see how they may have changed.

That's where I would notice specific punctuation points that are part of the narrative, where there is some object or character with magical properties that would get repeated in the drawings and change in her stories. These punctuation points help drive the work, and it's a moment in the whole narrative that points back to my mother and myself as both tellers and inheritors of the folklore. They are the main elements that get translated into sculptures and drawings.

One of the stories is about her cousin, who was bewitched and pulled into a tree. This image was striking to me, a gesture of a tree having some limbs, pulling and elongating a body. In my work, two cuts lie (2019), it was really an exploration of these tree limbs grasping at an invisible body.

As a kid hearing your mother’s stories, did you believe them to be real? When did you come to recognize them as being fictional?

KG: I don't think I ever literally believed in them, but I did think there was some truth hidden within the fiction. Sometimes current popular culture is woven into the story whenever she's telling it. There's a performance to the act of telling the story, and I often have to parse through what's the real story and what is live editing.

I can't help but see the parallels between her story and the Filipino identity. In Philippine history, a tactic to preserve culture while being colonized was to merge folklore with religion. In some ways, that's how I view her stories; they're real accounts but merged with fantasy to preserve the narrative.

Can you tell me more about how fiction plays into your work?

KG: In some ways, fiction is a kind of prompt that pulls from a lived experience. The retelling of a real past gets warped, reimagined, and reinterpreted– similar to that of a dream. I think it’s essential that my work exists as fiction because it leaves room for processing levels of trauma and multiple perspectives within a social dynamic. In terms of collaboration, fiction also opens up a generative site to allow for more ways of engaging different viewpoints. It becomes a really exciting conversation that is outside of just my singular voice. It’s a kind of distraction that tricks you into dealing with real obstacles or social tensions in a roundabout way.

My last project was a collaboration with Amy MacKay, my studio mate. We were exploring this American fiction called the Hidebehind, a story about a monster with an unknown shape or form, always hiding behind something in the forest. This folklore served as a vehicle for Amy and me to investigate how to share space and communicate presence to another person with a different material vocabulary. The Hidebehind became a metaphor for ‘the other’, paranoia, misunderstanding, and the sincerity of wanting to connect.

Do you intend for the viewer to know the full details of the story behind each piece?

KG: I like to operate with a bit of opacity. I like having layers in the work that are private, some that are recognized by a specific community, and other layers that can be shared with a larger audience. I think of my work as having multiple stories and perspectives woven together; this includes the viewer's interpretation. Although most of my work operates in abstraction, there's still something that the viewer can see and recognize.

As an example in the latest work, I've used an assortment of green bottles: sake, Squirt, Sprite, and 7-up. I am interested in them as this cultural remedy for stomach aches. I'm specifically choosing these green bottles because they are also the same color as a Filipino cure-all ointment that my mother used on me all the time. These items act as potions and remedies for their ability to treat a wound and are a visual cue for the audience to use for interpreting the work.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the idea of heirlooms and keepsakes. How do you see your sculptures interacting with each other in the space that you've created for them and then in their future life? How do you view them as objects?

KG: My work's charms and medallions are markers to commemorate something from a past series or interaction that runs parallel to the current series. I was inspired by Zöe Crossland's essay, "I Make This Standing Stone To Be A Sign," where she talks about how these ancient stones are records of a past that speak to an unknown future and, through time, lose their original intention to adopt a new context and meaning. And in a way, my solo exhibition in 2019 at Best Practice in San Diego might have been the first version involving these kinds of past object remnants. How these object markers take form depends on the context of the series. In the she haunts series, these charms have shifted into heirlooms or keepsakes because of the subject matter, but I can imagine adopting these moments in future sculptures to build a growing vocabulary with sentimental power in my practice.

And what's your relationship to objects in your life? Are there any objects that have been passed down in your family that have stuck with you?

KG: Objects have always carried charged meaning for me as something that contains memory, history, and power. I have two pendant necklaces from my mother. One has the initial G, which represents my mother's nickname, "Girlie," and the other is a jade circle and is supposed to bring protection.

I always thought of these keepsakes or heirlooms as a way of feeling like you're not alone while carrying some energy from the gifter. This sentiment has trickled into the work through necklace chains, charms, and talismans.

Can you speak about the physical and sensory component of your work? What are you thinking about in terms of a person experiencing each piece?

KG: When I'm making sculptures in the studio, I make them through my body. It's like a dance, where my body directly converses with the material's weight and gravity, and we're trying to tell a story together through overlapping forms. I'm thinking about negative space, how to carve that space where the viewer moves through the work, and how active I want the viewer to be within the installation.

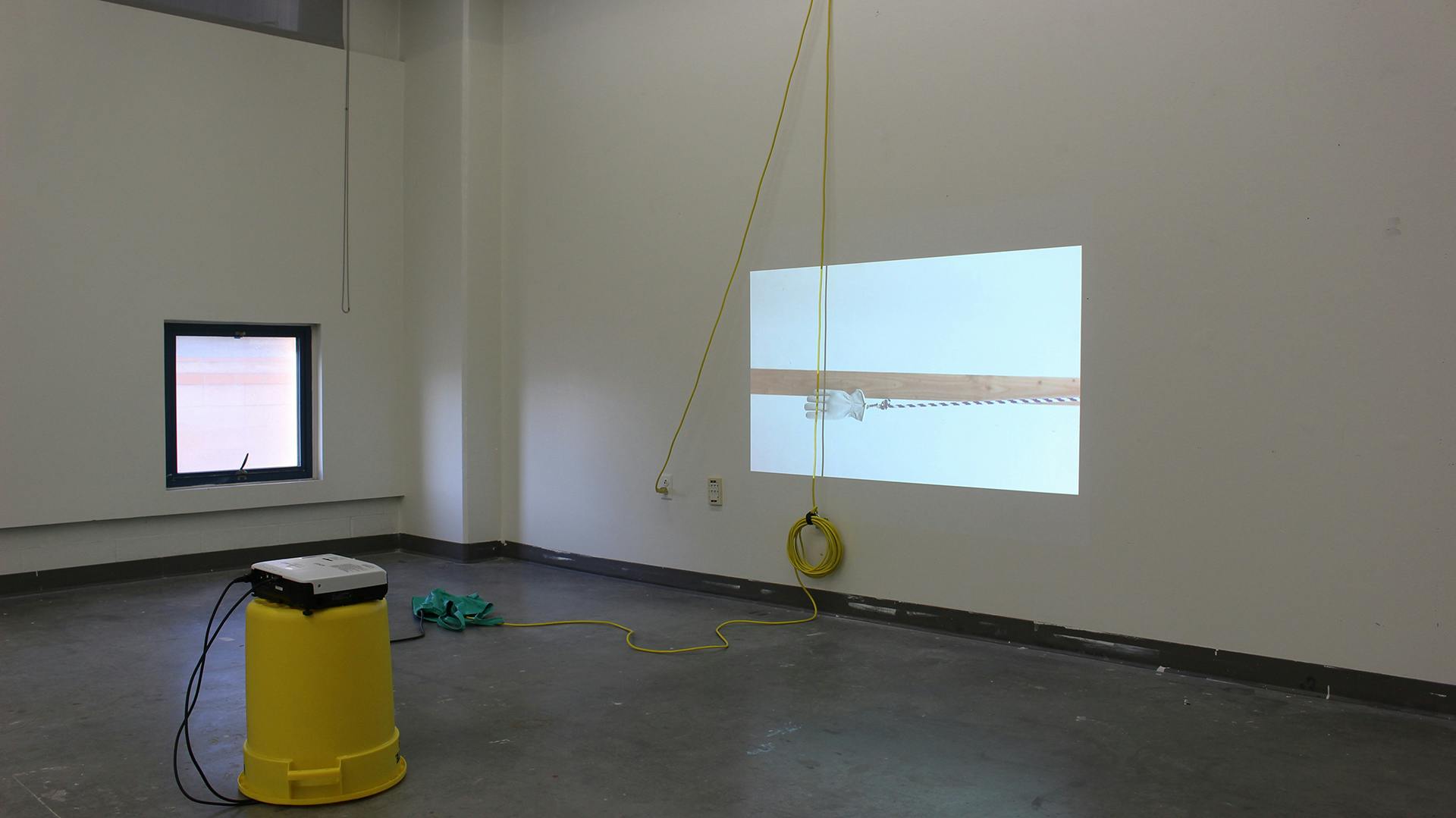

In a past show, is love a tender thing? every sculpture was made out of a multitude of objects precariously placed to balance in space. There was an element of playfulness where viewers had to be careful not to knock anything over. In that installation, stretched videos were projected in the background of the sculptures, setting a tempo or scene to help the viewers navigate the abstract forms. I wanted the videos to help illuminate a past event that may have occurred in the gallery, and I wanted the viewers to investigate the remnants of that abandoned stage.

In another show at Best Practice in San Diego, I was interested in making the viewer have an active role where they had to make deliberate decisions on how they viewed the work. I had these very low sculptures that acted like a pedestal for smaller works, and in conversation with them were these bright red drawings that were mounted at a higher height. The viewer had to choose between crouching down to view the sculptures or looking higher to see the drawings. I was interested in creating these delays in the viewing experience, where the viewer would be forced to direct their gaze on one object at a time rather than absorbing the work in one go.

A constant question I think of is, "how long can you sit with a work?" I think it takes a bit to unpack the pieces by looking at them longer. So when I have the opportunity to enact these installation strategies, I get really excited to build a world for the viewer to actively participate in.

You’re using striking, bold colors repeated in a lot of the works. Can you tell me more about your color palette?

KG: When determining what color fits a form, I always think about what kind of tone or attitude I want the piece to occupy. I lean towards specific palettes for their ability to feel alien, powerful, and at times, mischievous. I pull from colors that align with the content. At times they're from what I remember from the story or interaction, for example: a red lipstick with magical properties. Other times, it's an additional layer to the work that brings another access point for the viewer to engage with. Lately, I've been obsessed with this phoenix and peacock palette. I've been excited by the symbolism and cultural references between these birds and how one operates in mythology while the other exists in reality.

How would you say your practice has changed over time?

KG: It has changed a lot visually, but the overarching themes are still very similar. I like to think over the last decade, I exhausted as many configurations as possible to finally get to a material vocabulary that feels most exciting.

In my older work, I used a lot of ready-made objects and assembled them in a way that they performed in space, directly in conversation with video; it was more sparse and leaned very heavily on installation. The newer work is a more materially involved process using a hybrid of sculpture, drawing, and painting. This process helped me get more intimate with the materials and content, whereas the ready-made objects felt almost scientific and had a little distance. I also think sharing a space for the past seven years with a painter helped encourage a more prominent exploration of color. Secretly, I'm always trying to transform and merge all the different forms my practice has taken - who knows what it’ll look like in the future!

What do you do when you're not making art? How does your life outside of the studio influence what you're making?

KG: When I'm not in the studio, I have a jobby-job as a Studio Manager for a Designer. It's fun because it's not exactly in the same world but runs tangential to the art world. The business side of things at that job is really applicable and helpful for me as a working artist. It's also 5 minutes away from my studio, so it's a really easy commute after work. I also teach Sculpture (aka Spatial Studies) at the University of California Santa Barbara and run an online critique group called The Cold Read. The Cold Read is an email-based critique I started in 2018 to continue a conversation that seamlessly fits within an artist's hectic work/life schedule. Basically, one person presents their work, and the rest of the group takes a week to write letters in response to the work they're viewing. I set up this format to allow for an extended time for thinking about a work, rather than a standard critique setting where it's just the first impression within that first hour of experiencing a work. I also co-direct this project space called after hours which hosts 2-person summer exhibitions. I have many community projects ongoing simultaneously while working a jobby-job and maintaining a studio practice. But since my work relies on social dynamics within interpersonal relationships and community structures, my daily life activities directly influence and inspire the subject matter in my work.

We've talked a bit about your upcoming solo show–tell me about what's next for you once you mount the show?

KG: There are a few things that are percolating in my mind. I am still shooting to pick up on The Hidebehind collaboration with my studio mate. However, it all depends on the timing of our schedules. At the same time, I’ll start shifting my focus after the show towards a new project that explores my Dad and his near-death experience.

I feel this immediacy with having older parents, and I feel like I need to unpack, archive, and confront my relationship with them while I still have them here with me.

Learn more about Kim’s practice and works now available on Testudo here.