Published August 19, 2022

Who Gets to Rest? In Conversation with Christy Chan

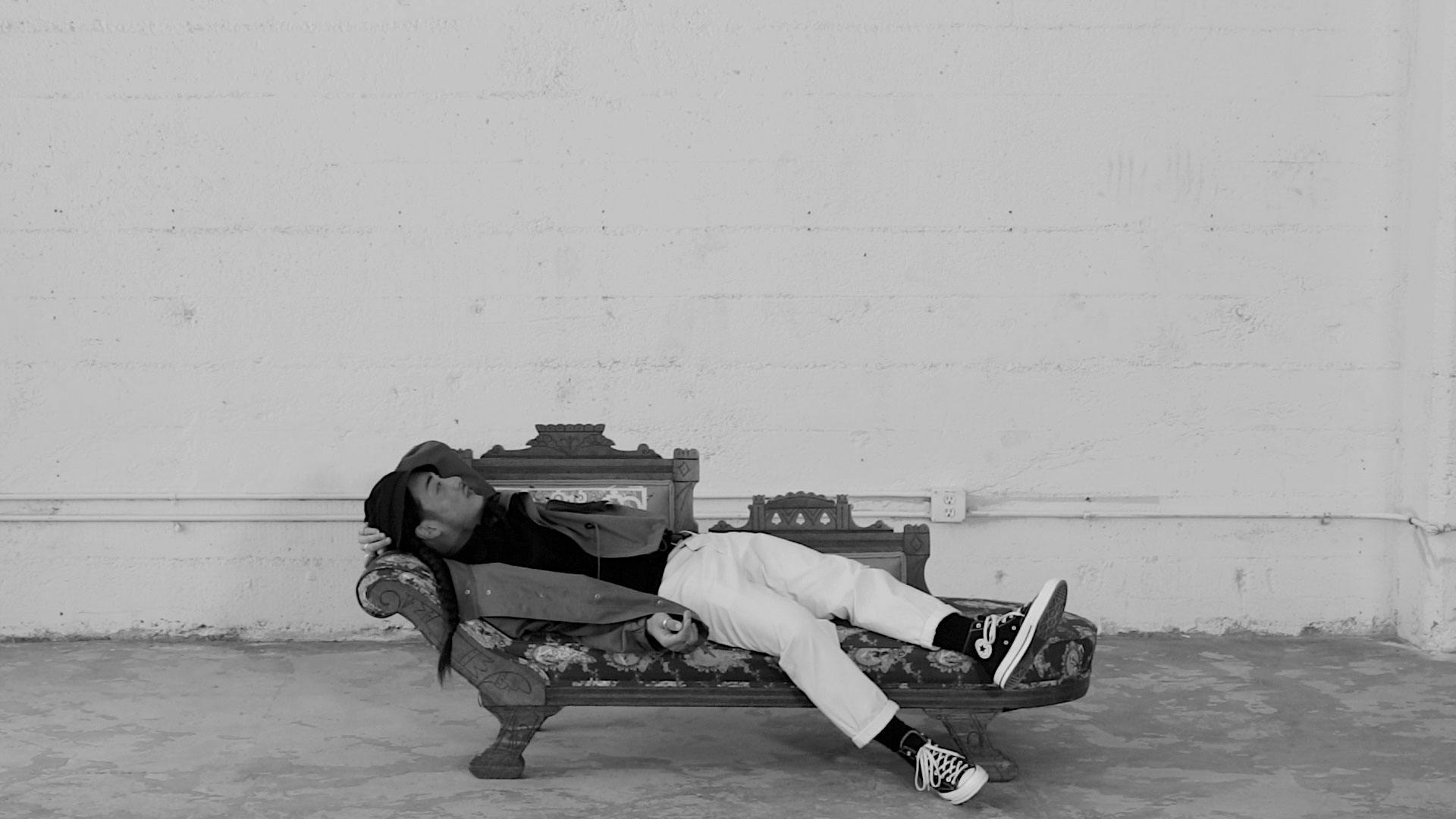

With her public art piece, Fainting Couch, Christy Chan, wanted to explore privilege, white supremacy and who gets to rest.

Chan, an interdisciplinary artist and 2022 Guggenheim awardee, grew up in Loudon Country, Virginia, where children were expected to pledge allegiance to the Confederate flag at school and saw fainting couches in the homes of her friends. Looking for ways to examine white fragility, Chan hit on the idea of getting an antique fainting couch, which she worked to transform and re-upholster. She also took videos of people “fainting” onto it and projected them onto a building at Mills College, where her show, Patterns, is on view.

Last year Chan did a project, Dear America, where she and other Asian American artists projected large-scale images of their work onto buildings, sometimes without permission. Along with the images, there was text in English as well as in Asian languages, with messages including “Dear America, Fix Your Racism,” and “White Supremacy is the Original Cancel Culture.”

Chan talked about why she wants to make her projects participatory and make public art for everyone. She also explains why she used peacocks on the textiles for the fainting couch and what receiving the Guggenheim meant.

How did you hear about fainting couches? When did you think about doing this project?

CC: I knew about fainting couches growing up because there traditionally were a lot of fainting couches in the South, and a lot of people I grew up with had them in their homes that had been passed down through generations of family members. So, I was always aware of what they were for, and I began thinking about them three years ago when I started actively doing research on projects that could examine white fragility and intergenerational privilege.

The idea of sourcing a fainting couch and transforming it into a touchable artpiece was one of the first ideas that came up. I wasn't sure at first how feasible it would be to even find a fainting couch. I wanted an authentic Victorian era fainting couch, and those are hard to come by. A lot of them are not in good shape, and the ones that are in good shape are sometimes in museums as artifacts.

The idea came up all at once, in a way. From the moment I thought of transforming a fainting couch, I thought it should be participatory. People should be invited to lie down on it because traditionally speaking, fainting couches were exclusionary objects. They were mostly in the homes of wealthy white families, and it was specifically for use by the lady of the house because in those days, women of the upper class were corseted and they regularly would lose consciousness, so there was a functional need for these fainting couches.

It became a socialized norm that women of privilege losing consciousness was not only normal but should be supported. That's why I wanted to explore it as a public art idea because I think in so many ways, it's a unique metaphor for intergenerational privilege, right?

I was actively looking on antique sites. I was looking on Craigslist and on Facebook marketplace. At times, I would find a fainting couch that seemed ideal, but it would be in Missouri or South Carolina, and I didn't want to ship it that far. So, it took about eight months.

The one I ended up finding was on Facebook marketplace. It belonged to a family near Sacramento and had been in their family for many generations. They just didn't want it anymore but kept it in good shape.

That's my long answer — the idea came up in the midst of a three-year research project that I was doing about white fragility.

The textile design on the fainting couch is green with delicate birds. How did you choose the fabric and design?

CC: I spent maybe six months just researching textile design. Textiles tell stories of the years they were made. They tell stories about who had access to them, who got to purchase them, and the materials. This was a digital collage, and it felt important that it nodded to some of the patterns from the Victorian age without being literal.

A lot of birds were used on textiles in that age, and I chose to use peacocks because they are considered some of the most beautiful birds, right? But they're too weighed down to fly, and what we perceive as their beauty is what makes them non-functional. And they can also be quite loud and violent. I also intentionally collaged peacocks that look somewhat corseted, their plumage is not released. The digital collage in my textile design is essentially birds collaged with human arms in a fainting position.

The colors I chose are mostly greens and blues. There's four or five different shades of green and two different shades of blue in there. I looked at a lot of archival Victorian textiles, and one of the things that came up during my research was that up until a certain time in history, everything was beige, or cream or brown in interior decor.

But then during the Victorian era, someone figured out, “hey, if we want to make the color green, all we have to do is put arsenic in the materials.” So green became this iconic color —it became a status color in a way. If you walked inside someone's home and they had green wallpaper, it meant they were probably wealthy because it wasn't something everyone could get.

Of course, a lot of people got sick from arsenic poisoning, but what I found interesting in my research was that after that became known, a lot of wealthy families took a long time to take their wallpaper down. Their reaction to this news was, "But how can something so beautiful be bad for us?" So, in many ways, green was the color of denial in Victorian times.

My intention with this work is to create an open, participatory platform that goes in the face of cultural patterns. Something that informs all my work is the notion that who gets to have a voice is the battleground of our culture.

People have called this work beautiful. What's your response to that?

CC: As someone who makes a lot of work critiquing white supremacy, it's not often people tell me that they find something I've made beautiful, but in this case, it was very intentional that I wanted to examine the fact that beauty is an illusion.

With the fainting couch, I wanted to make something that looks beautiful on the surface, but when you really get up close and look further, there's another narrative there. When someone looks closer, they can then see what the textile is really narrating and that it's essentially images of disembodied limbs, right? For me, it's a metaphor for showing that what we consider beautiful in our culture is actually full of violence. I wanted to play with the illusion of beauty and the illusion of innocence.

This project is going to travel around, including going to the South, where you're from. How do you feel about it being on display in the South?

CC: We are still very early in the process, and I am curious who will host it and how it will be contextualized. It's very different to show work about the South in California — or to show work inspired by the South. My intention with this work is to create an open, participatory platform that goes in the face of cultural patterns. Something that informs all my work is the notion that who gets to have a voice is the battleground of our culture.

So everywhere I take this couch, my intention will be to make it a touchable art piece and platform for storytelling for people who may not typically participate in the arts. It's not necessarily going to be comfortable for all audiences, but it's going to be very accessible to all audiences.

Again, in its heyday, a fainting couch could only be touched by the lady of the house who was in position of privilege to rest on it. This couch is loaded with exclusionary narratives.

By taking this couch around the country and making it available as a participatory platform for storytelling, I'm inviting people to decolonize the couch and take up space with their stories. Each place I'm invited to take the couch, I will encourage my hosts to really reach out to local communities beyond who might typically patronize or visit their space.

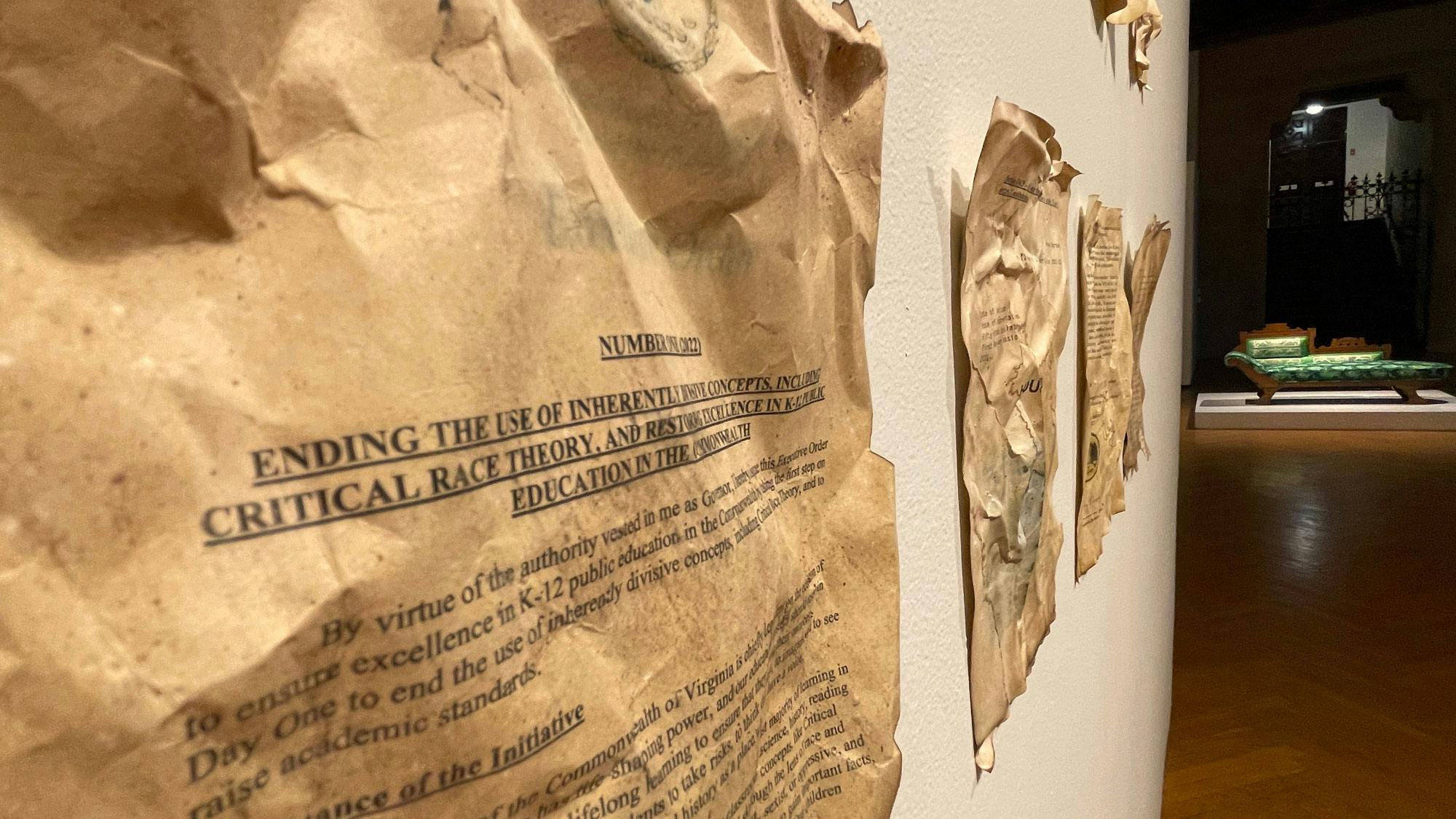

Part of my motivation for the whole show is that we're living in a time where there's disproportionate censorship of writers of color, and critical race theory is being banned in 14 states. So, now more than ever, I want to create projects that create space to tell the truth.

No matter what's happening politically, art can be a powerful way to create space for people to tell the truth. That's a component of the show as well. After people rested on the couch, they were invited to write their stories down, and a lot of those stories were turned into a video.

Christy Chan, Highlights of the Dear America projections project. June 1 through July 30th, 2021, Courtesy of the artist.

How does this project fit in with your other work like Dear America?

CC: My past projection projects have overlap with activism because on some of these projects, I didn't ask permission. The overlap between this project and some of those past projects is I want to disrupt the narrative of who gets to take up space with their voices. Perhaps another overlap is that my projects are meant to be participatory. In this one, 70 people participated just in the Bay Area. So part of my thinking, behind this work and the Fainting Couch traveling, is that the larger show, Patterns, was about patterns of intergenerational gaslighting. But just as gaslighting is intergenerational, so is authentic storytelling.

What's the significance of the timing of the show?

CC: The January 6 insurrection was a motivation for me to follow through with this project. While the idea came up in either 2019 or early 2020, As I mentioned, finding an authentic antique couch that had a history wasn't easy. There were times where I thought, "Okay, maybe I won't keep pursuing this." But as a citizen watching what's happening in our country with the banning of critical race theory, the insurrection, and as someone who grew up around Confederate culture, I was motivated to make the project happen.

In my elementary school, we were expected to pledge allegiance to the Confederate flag, so I grew up with patterns of gaslighting like a lot of people. When I watched the January 6 insurrection happening, and I watched the Confederate flag being carried into the Capitol, to me, that was just another reminder of the level to which people are gaslighted and continue to gaslight each other.

I should mention too that the town I grew up in, is actually the national hotbed of critical race theory. It was one of the first school counties that banned critical race theory. And things got so heated there that people, who didn't want the Civil War taught from multiple perspectives and who didn't want the Holocaust taught, were taking guns to school board meetings.

So having grown up in Virginia and now living in California, I’m doing work that is informed by my experience of being a transplant from the South. I felt this was a project I needed to do.

By coincidence, the week the show was installed week was also the week we heard about Roe vs. Wade. This show never felt like it was just about making art. So, this entire show, it never felt like it was just about making art.

What has getting the Guggenheim meant for you and your practice?

CC: The award has been such an incredible gift to my practice. Because a lot of my work has been about critiquing white supremacy, that has in some ways required me to encounter gaslighting within my work.

I'm an artist who makes work that critiques power systems, and that flies in the face of what the stereotype of Asian Americans are and what Asian American women are expected to be. In making the work that I most want to make, I frequently have to navigate patterns of whitewashing that are just built into our culture.

We have these limiting perceptions of who gets to narrate the story. There's a piece in the show of a sculpture of a flag made with 15 years of essays and letters I've written when I had to take corrective measures to make sure I and my work are being fairly represented. I guess the Guggenheim gives me hope; it gives me excitement, and it encourages me to keep making the work that I want to make from the heart. I see making artwork as a combination of heart and muscle. And I never want to stop making art that doesn't come from the heart.

Receiving the Guggenheim has given me a sense of freedom that I can, at least for the time being, keep pursuing the questions I really want to be pursuing. It’s an incredible gift.