Published January 17, 2023

Poyen Wang on Filmmaking, World-Building, and Endearing Insanity

Poyen Wang is a New York City-based artist and filmmaker, born and raised in Taiwan. Working primarily with 3D computer graphics, his work hybridizes different cinema genres and utilizes analytical aspects of filmmaking to explore personal and collective emotions, with a focus on the queer and immigrant experience. Wang’s recent practice explores issues of identity, sexuality, and masculinity through a psychological lens.

He has held solo exhibitions at the Taipei Digital Art Center, Taiwan; 18th Street Arts Center, Los Angeles; Flux Factory, New York; and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts. Wang’s work was recently exhibited in Bronx Calling: The Fifth AIM Biennial at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in 2021, and will be included in “VIDEONALE.19—Festival for Video and Time-Based Art” at Kunstmuseum Bonn in Germany.

Poyen and I first met in Providence in 2017 and reconnected three years later in Taiwan. We gallery hopped across Taipei, worked together at an artist book fair, and supported each other through our US-visa journeys.

Ahead of his latest solo show, Endearing Insanity, at Essex Flowers, New York, Poyen and I caught up to talk about his semi-autobiographical practice, his influences, and his newest video work, Endearing Insanity, which is in the current show at Essex Flowers and will also showcase at Gallery 456 from February 24–March 17, 2023.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What was your upbringing like in Fengyuan, Taichung, and how did you first come to animation?

PW: Fengyuan is a small district in Taichung, so I didn’t grow up with much exposure to art. I would say that my upbringing was typical. In an environment where most Taiwanese parents want their children to be lawyers or doctors, I was raised with similar expectations of studying hard to get into a good school. However, I always had an interest in making and working with my hands, so I ended up going for a commercial design degree at the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology in Taipei.

A professor in my third year introduced 3D animation into our multimedia design courses, and that was where I first came across the medium. My first film was a short 3D animation made for my thesis project.

University was my first time out of Taichung. I had a lot of time to myself and soon developed a real passion for film. I would get student tickets to see films at arthouse cinemas in Taipei and film festivals such as the Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival. This new interest in cinema informed my 3D animation studies. I wanted to create film-like experiences, and that was possible with animation, where I didn’t need a whole team.

You’ve described your practice as “semi-autobiographical,” and the main protagonist in The Black Sun (2020) and Endearing Insanity (2021-2022) as a “surrogate,” an extension of yourself. How does that play into the world-building in your work? And does your upbringing have any influence on that?

PW: “World-building” is definitely a keyword I think about. Growing up in Taiwan, I was exposed to a lot of Japanese anime and video games. I particularly loved playing RPGs (role-playing video games) that had maps of fictional worlds to navigate through. In choosing the character that you play as, the character becomes a surrogate for you to experience the world of that game. I find that quite fascinating and see a parallel between RPGs and the I-novel genre in Japanese literature that I also enjoy.

The literature of Japanese writer Motojiro Kajii is an example of this confessional style, where the author and narrator is often blurred. I was inspired by this method of the semi-autobiographical for my body of work, The Black Sun series (2020), as I also resonated with the themes Kajii used to contemplate death, human existence, and motivations for creative production in his work.

My subsequent projects about self-exploration are grounded by a similar approach to examine identity, where the protagonist is somewhat between autobiographical and fictional.

Poyen Wang, A Recital (Excerpt), 2019-2020. 3D computer animation, HD video, sound 3:58

What are some challenges of working in this medium with the advancement of technology and digital tools?

PW: 3D animation is incredibly time-consuming, especially if you want to create natural, smooth movements. Unlike stop-motion or hand-drawn animations, the medium seeks to—and can—create very realistic resemblances. On the other hand, because of that, there’s also a real risk of it falling into the “uncanny valley”, where the human figure is stuck in this very awkward, not-quite-human, artificial appearance.

I agree with your use of the word “tool” and believe that as long as you have a good handle on the basics, it’s not necessary to learn every single new program or to have its latest, most updated version—I don’t want to be “controlled” by the medium that I use. Also, not every new technology will be appropriate for the work that I make. For example, I’m not interested in making VR work at the moment, since VR negates the editing ability in filmmaking.

During your time at SVA, you focused on creating installation art and experimented with a range of materials (e.g. A Fabricated Personal Archive, 2017). How has that experience influenced or changed your animation and image-based practice?

PW: My MFA studies at SVA was my second Masters, the first one was at the Taipei National University of the Arts in New Media Art, where I expanded my knowledge in contemporary art and focused on developing a video art practice. Since I have been making 3D animations, I think my time at SVA Computer Arts did not have that much influence on my practice, but it granted me an opportunity to explore different materials. The program was intense and very technical, so the work I made during my time there was related to my school time. For example, Construction of Intimacy (2016) was made for a digital fabrication class, and in Route of Obsession (2016) I explored performance art and conceptual art.

I’d say that the main influence my two years studying in New York City had on me was the opportunity to see a lot of exhibitions in museums, because it expanded my understanding of what an art practice could look like and be about. And my time at SVA computer arts strengthened my skills in making 3D animation and videos. I think the work I made at SVA provided a foundation for my latest image-making practice and aligned with my interests in exploring desire, the self, alienation, solitude, and passage of time. These are all topics I continue to think about.

You often explore the intersectionality of your queer identity, along with dualities between the public and private; the self and other. What does it mean for you to unpack these themes through a realistic, photographic style of animation?

I think a lot of what I’m exploring has to do with the experiences of everyday reality and the psychology of dreams—I want to hone in on examining mindscapes and psychological worlds, so it seems appropriate to use a more realistic style. What I think about more is the idea of Magical Realism, where magical moments are woven into reality. The Japanese cultural critic Hiroki Azuma, who proposed ideas about Anime Realism, influences my understanding of creating a stylized aesthetic and environment rooted in reality. The settings in the anime by artist Makoto Niitsu are often actual places around Tokyo that you can visit.

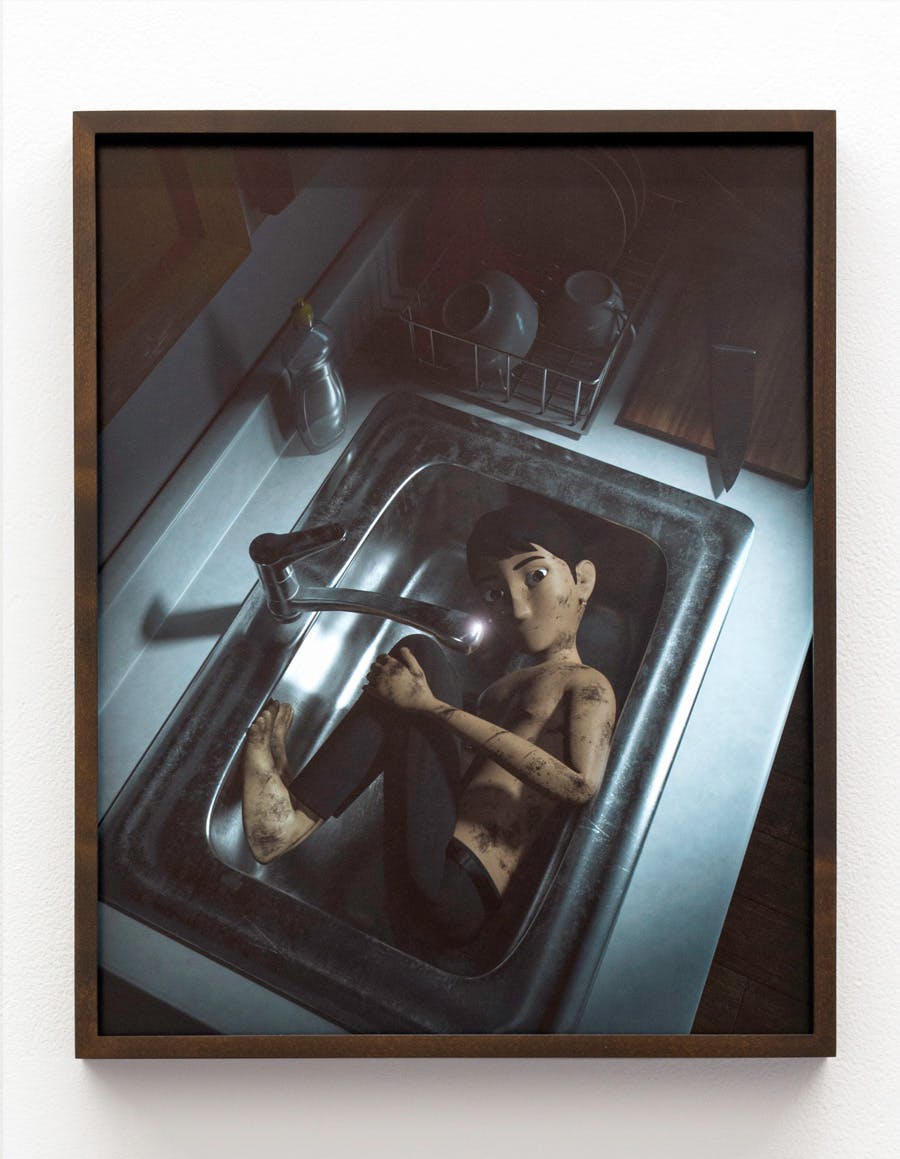

In my own animation, you can see this in Endearing Insanity (2021-2022), where the kitchen scene actually references an old apartment of mine in Brooklyn.

Yes, the entirety of Endearing Insanity takes place in that very specific domestic space. As the first work of yours that was edited to audio, what role does sound generally play in your animation?

Sound only recently became an important part of my work. My earlier animations were presented as video installations where sound was non-existent, or only added in as ambient noise.

Endearing Insanity is informed by Julia Kristeva's theory on abjection. In thinking about the primary abject of the infant’s separation from a mother’s womb, I wanted to have obscure, liquid sound effects that disrupted the space and guided the animation. The disruption is heightened in the occurring monologue that is narrated with a muffled voice. I think for this piece, sound played an important role in creating suspense and horror.

Both The Black Sun and Endearing Insanity have strong literary references. What are you currently reading? What are you excited about exploring next?

PW: I’ve been reading Ocean Vuong and revisiting a collection of short stories by Taiwanese writer Yan Shu-xia. Again, I’m interested in the semi-autobiographical, and enjoy the poetic language from both these writers. While some of the writing can be very dark, I find them incredibly vivid.

Yan’s essays deal with familial traumas in a similar way to Vuong. Having been in New York City for a while now, I find myself missing reading in Chinese. So, I resonate with Yan’s words a lot. They’re quite visual for me, I’d even say they’re magical realism, as her stories exist between reality and her own memory. This is something I’m interested in for my work too. For the new animation I’m developing, I’ll also have monologues, and want to explore using found text in my narratives more.

You’ve previously mentioned that you hope to create more artist films in the future. What is the storytelling distinction between film and video art for you?

PW: I think the main difference is narrative. For me, artists like Bill Viola and Vito Acconci create video art that is more about the installation without much narrative. You could come into the work at any time. However, I’d say film requires one to watch from the beginning to the end. Even for directors like Tsai Ming-liang, whose films don’t always have much dialogue, there’s still a progression in its story, with careful composition between the image and sound. Although I think this distinction is becoming blurrier in contemporary art, it’s something I still consider for the structure and display of my work. With my recent interests in non-fiction filmmaking, I’m looking forward to continuing exploring and making artist films.