Published February 14, 2024

What Lives in the Empty: An Interview with Trevor King

This interview is the first in our new DIALOGUES series, which connects Testudo artists to explore their respective practices. In each conversation, a new Testudo artist will take on the role of interviewer, bringing an exclusive look into the studios and creative practices of our artists. With over 45 partner artists located in 12 states, DIALOGUES supports a rich, cross-regional exchange among our artist community and beyond. Follow along here for new conversations and artist pairings, only on Testudo.

Space is Not Enough is a solo exhibition by artist Trevor King, now on view through March 1 at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Growing up in Butler, PA, King mines his childhood environment and personal family relationships to show us that empty, abandoned spaces still have a sound and that his cousin Randy's room is so much cooler than our own. Pittsburgh-based artist Sidney Mullis met with Trevor for a walk-through of the exhibition earlier this month. After the visit, the pair sat down for a conversation on object making, drawing from historical and personal archives, and mentorship.

Upon entering the exhibition space, I noticed that a lot of these objects have a voice. There is a humming vessel, a cautionary painting, and a clay neon prayer. There are so many low echos, hums, and whispers coming from objects that are generally regarded as inanimate. For you, what makes something alive? Do you think about these objects as alive?

TK: Thanks for pointing that out!

I think that a lot of the time I'm not only interested in the subject that I’m working with directly, but what sort of residue or echo it carries along with it. Sound, for me, is a way of animating something that is inanimate, and ultimately a way of blurring the edges of where it begins and ends. Sound is a great sculptural material because it can feel so vast and immersive, and this is a feeling that I’m trying to instigate in all of my exhibitions. I want viewers to feel like they’re within the work, so seeing the show becomes an experiential activity, rather than looking at something that is outside of you and not interacting with your world.

One of the first artworks that I ever thought “worked,” or achieved the things I wanted it to achieve, is a video titled Thanatopsis Clocks, which uses audio tapes that my grandfather recorded while traveling in Florida in the early 90s. He’d record tapes as letters and send them home to us to listen to. There was something about using his voice, and reflections on daily life, and the preservation of the past that gave me something to work with. Because it was non-fiction, it felt like the artwork contained something real and consequential.

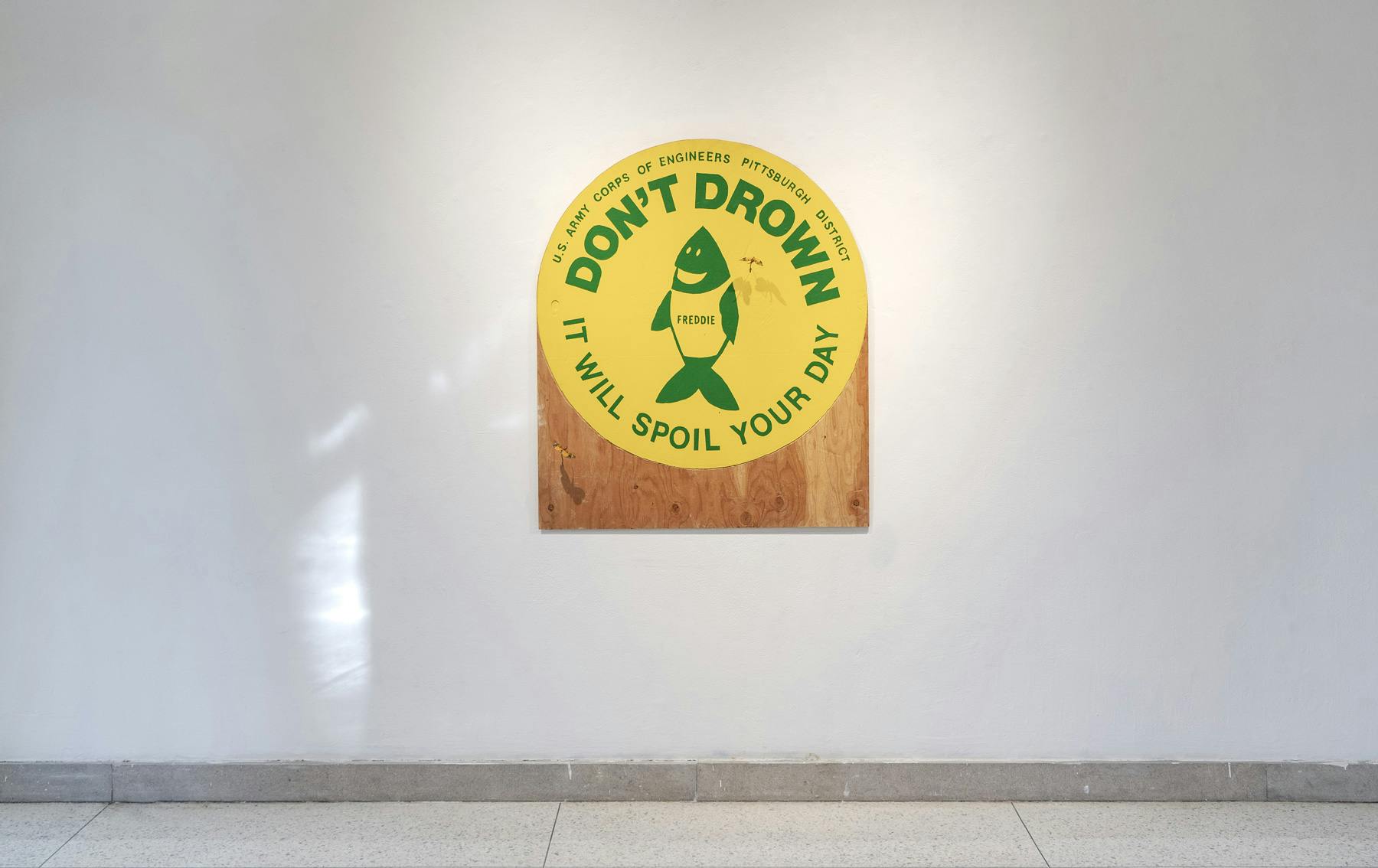

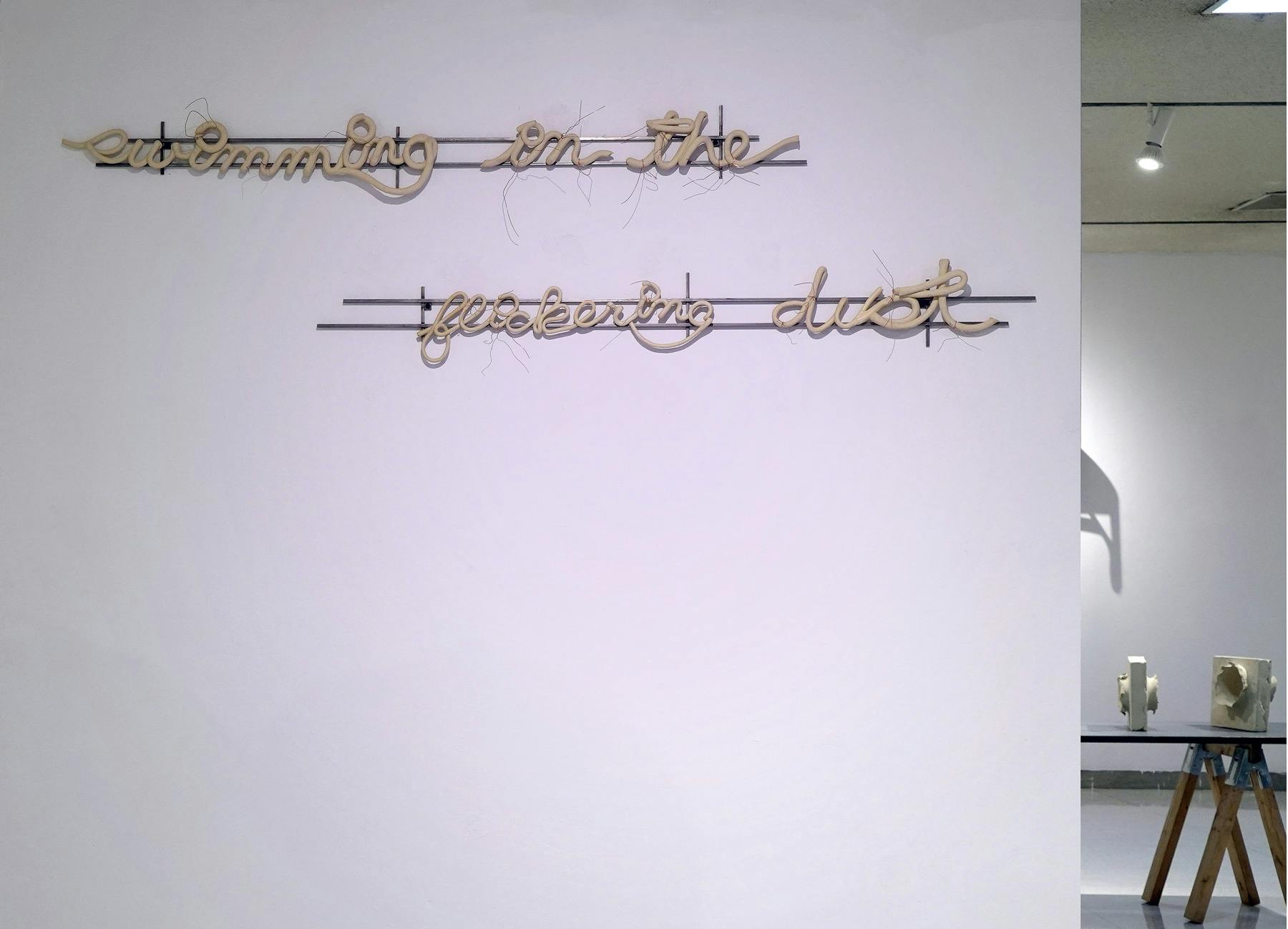

I like using text and dialogue because it lends itself to interpretation; it's obvious that there is always more to read into it, and probably more that is unsaid. In Space Is Not Enough, I have at least three allusions to swimming: the Bathers video which shows cliff jumpers in a distorted projection, the Clay Neons/LED that read, “swimming in the flickering dust, floating in the fog that lifts you,” and the Don’t Drown painting. All of these pieces refer to the feeling of saturation and suspension that I like my work to have, while simultaneously referring to real histories. The Don’t Drown painting is an exact enlargement of a pin that I got as a kid at Shenango Campground, which is about 35 miles from Allegheny College. I’m interested in this piece as a way of studying and preserving history, and studying the visual sensibilities of the world I grew up in. Why is the fish’s gill used to create a strange smile, why does it have a tank top, and a name?

So getting back to the core of your question, I think that I’m using these devices to talk about the residues that exist on objects and in spaces, so that the viewer can almost look through the pieces and observe the intensity of the momentary or the persistence of the passage of time.

Your question also makes me think about my making process and the ways that I like to present artwork. I’ve always been kind of a shy person. I’d prefer to be on the periphery than the center of attention, and when I was young, I was always told that I was a mumbler. I’m sure that I like to make art quietly, almost in secret, and then present something that can speak for itself, and hopefully in a stirring and piercing way. When I make a piece and present it in a manner that I’m satisfied with, I feel a great sense of relief–like I’ve been able to say exactly what I mean to say, and that I’ve been able to point something out even though it might be nuanced and quiet, and sometimes difficult to see.

In your work, I think a lot about the blurring between absence and presence. In the video projection Bathers, we see cliff jumpers come in and out of focus as we wait (tensely) for their heads to pop back up out of the water. In your exhibition statement, you share that your show title came to you while waking up, a process of coming back to presence from absence. It seems that you are not only interested in heightening absence/presence in your work, but also your process is about observing what exists in the empty. Can you talk about how this occurs in the artwork and in your working process?

TK: This question makes me think about that absolutely heartbreaking song by Jason Isbell, “If We Were Vampires,” which is sung from the perspective of someone who is deeply in love, considering the terrifying probability that one member of the couple will pass away before the other, leaving one of the two to live on in grief. My grandmother is going through this right now, and since my grandfather passed in 2018, she's developed dementia and gets confused, thinking that he is just out running an errand or something. It’s heartbreaking.

I think this ties in with your first question, and there is a lot of overlap between the two. With the Bathers piece, I’m trying to make my response to the art historical precedent and ubiquity of Impressionistic Bathing scenes, and when I think about that world I think about cliff jumping. The piece is about looking at the extremes of the human condition, the great lengths people will go to feel alive.

This also makes me think of a moment from the video piece, The Enormous Room, which was filmed in my apartment during the first weeks of the Covid lock down. I remember during those first couple weeks thinking a lot about breath and air as this precious thing. I was even afraid to open the window. There's a moment in that video where the sunlight is casting a beam of light into the apartment. I’m walking around getting some light on my feet and my wife Clara is moving her toes around creating dust. She’d call it the “dust show” and it's this visually beautiful thing, while at the same time it feels like this message–like “there we are turning to dust in real time, transferring into something that's boundless.” This video and that moment in particular really encapsulated the complicated feelings of that moment for me and broadly that’s what I’m trying to do with my work: to study the states and conditions of the moments we’re in and to make a functional and poetic record of it.

There are a number of works about rooms—The Enormous Room, Several Empty Rooms, Several Rooms of Flashing Lights (Randy)—and yet the title of the show admits that Space is Not Enough. Which one came first? Can you share more about the title of the show and how it relates to these artworks?

TK: Hah! Again, thank you for discovering this and pointing this out. The titles of the individual pieces came first. When I planned this show, I wanted to bring together a bunch of what I feel like are my strongest pieces from the last few years, and see how they inform each other.

When that title came to me, Space is Not Enough, it made me think about the spaces that are depicted in the exhibition, like Randy’s room, or how our apartment is explored in The Enormous Room. All of these places are extensions of people, and descriptions of who they are, and how they build worlds, so the depictions of the spaces are depictions of the humanism that made them. The title also made me recall spaces of incredible natural beauty, like Horseshoe Canyon in Utah or the Italian Dolomites. I go to nature to experience profound and overwhelming beauty, but I'm not sure that the beauty of nature would matter without people.

Mentorship seems really important to you and your practice. You acknowledge and celebrate your mentors in your artwork, such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Modest Mouse singer Isaac Brock, and James Turrell. Why is mentorship important to you and to put it into the artwork? Why are these masculine figures important to you? Do you consider them part of your (imagined) family tree?

TK: Absolutely. In fact, I've made pieces that are specifically about my mentors, like the video piece titled “Profe,” which portrays my first pottery professor, Richard Wukich, on his farm as he discusses pottery from a historical and philosophical point of view.

I’ve been extraordinarily lucky to have mentors who have become close friends and colleagues, particularly because I did not know many working artists when I started this journey. I met my friend Ian F. Thomas when I was a student at Slippery Rock University, where he was a professor. He’s been a pivotal voice through the development of my practice and made this show possible. My exhibition, Space is Not Enough, is presented in parallel to an exhibition of his work, which looks at childhood innocence and gun violence. I think that if you were to look at both of our shows you could see a lot of parallels in how we approach materials and object making as tools for storytelling.

I think that it's been easy for me to identify with masculine makers like Thomas Houseago, because there is a desire to make these large encounters, and to get into wrestling matches with the work. The figures that I’m making are particularly inspired by that impulse. I’m massively influenced by Raymond Carver and Isaac Brock because they both talk about class, personal demons, and the calamitous nature of life. The artwork in the show that uses Modest Mouse lyrics is a drawing, a blueprint for a future installation that would use Christmas lights to read, “it’s hard to be a human being,” which are lyrics from the song, Baby Blue Sedan. I think that those lyrics are powerful simply because they’re honest.

I love the sensitivity of Felix-Gonzales Torres, and that I can relate to the sense of loss in his work, even though we’re coming from very different life experiences. I made a version of one his pieces for this show, Untitled, After Felix Gonzalez-Torres which references his Untitled (America #1). My version of this piece is not nearly as clean as the original; you can see all of the wiring that has been spliced and connected by hand, and each of the lights are on plastic candles, like something you could buy at Kraynaks in Sharon, PA.

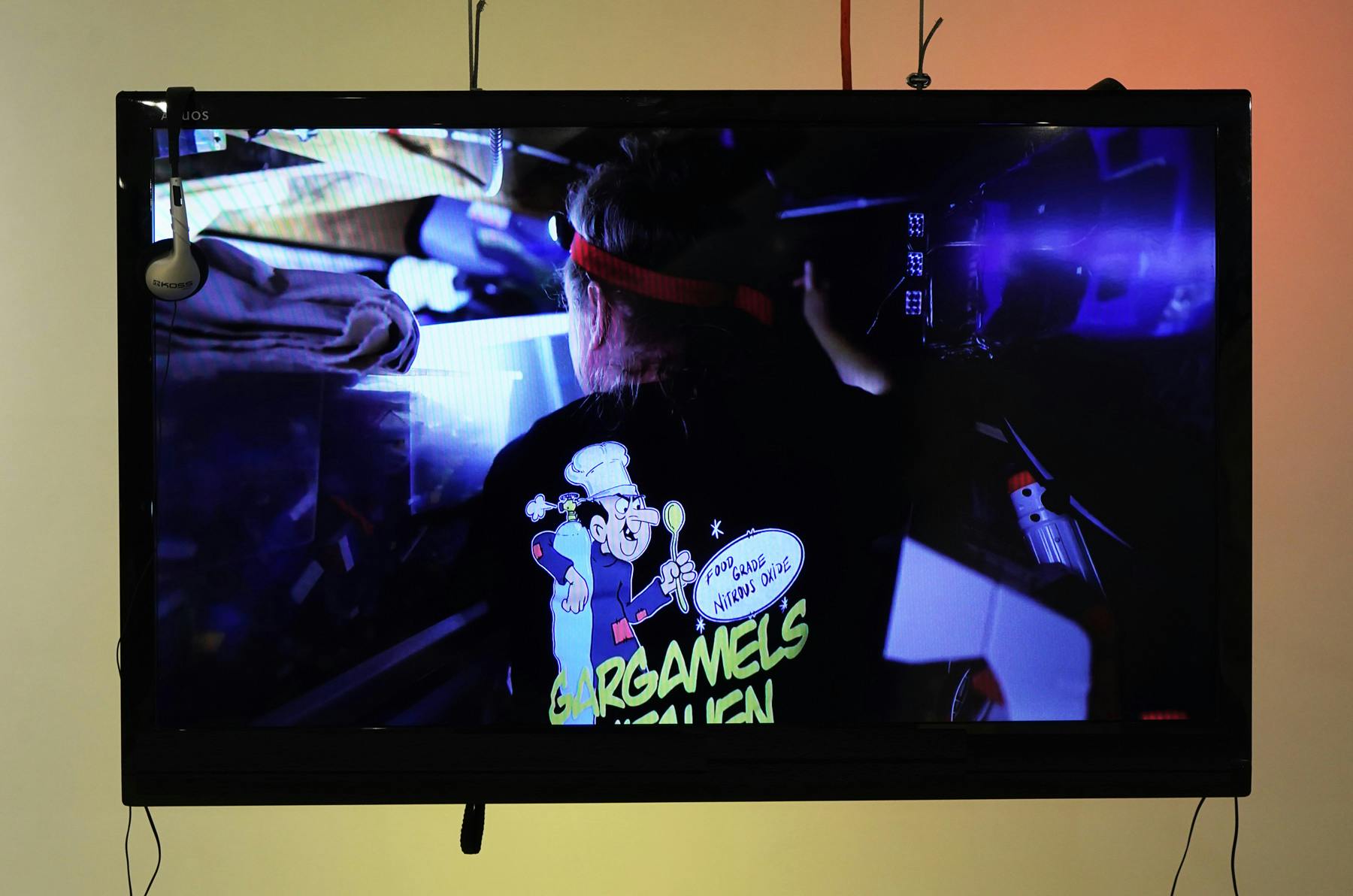

You also make artwork about your relationships with people in your family. In this show, Several Rooms of Flashing Lights (Randy), is a documentary about your cousin Randy, which highlights his amazing childhood bedroom/art installation and his later career as a lighting designer. The video is presented on two suspended TV screens that are back-to-back, making the viewer revolve around the objects to get the full content. How did this piece start? Where is it going? Will there be more chapters?

TK: I began filming this piece in December 2019, but the idea for the project probably began long before that. Randy is a fascinating, profoundly creative person, and his life deserves some sort of life story movie.

The video piece really began with the desire to somehow preserve the magic of his room, which still exists in its original setting in his parents’ house in Butler, PA. In the video, he guides the camera around the attic space, giving the viewer a tour of how everything developed, and what some of the objects mean to him. Every time I’m in that space, it’s like being transported to another world, and even right now I can recall the hypnotic clicking of the old fashioned carnival lights and the smell of rugs and wooden walls.

The other chapters of the video study equally dreamlike or hypnotic aspects of his life story, like the period of time when he was creating massive rave parties all around Pittsburgh and beyond, or his immense collection of home video footage, that becomes this sort of poetic multitude. I think that the whole thing is a portrait of Randy, a reflection on the nature of creativity, and a journal of life in the US from the 1980s to today.

I am hoping to grow this project – there is so much more to film and many other ways to show the various video components. With this presentation, it was important to me that the viewer couldn’t ever see the whole piece. You always know that there is something happening on the other side of the diptych, there are more facets to it than you can observe. Also, I like that this video portrait, which is a vast world in itself, is taking place within the center of the world of the exhibition. When you watch the video, you can see that I’m borrowing strategies from Randy’s Room in how I present the artwork in the show. There are a lot of things dangling from the ceiling and splotches of color throughout the show that use his old lighting gels from the rave days.

It's easy for me to imagine projecting the Randy’s Room chapter on multiple walls, translating the feeling of that space into a video space. I’d love for the project to somehow preserve that room. Maybe we could take a crane and cut off the top of that house, Gordon Matta-Clark style, and move the entire room to the Carnegie Museum of Art or MoMA.

You mentioned ideas are very important to you and that you want to try them out in many, different materials. We see examples of this in the show with clay, video, LED signage, and more. Where does this impulse come from? Does it help artwork feel finished or does it help artwork never feel finished?

TK: I think that this comes from the fact that my works are trying to create impressions, and there is probably no singular way to do that. With the works in this show, I'm becoming more comfortable with the idea that these pursuits, the immersive research parts of my practice, don’t need to have a conclusion.

There are a lot of works in the show that take the form of a diptych, or exist in multiples. Hopefully within those choices, you can see the things, but also the immaterial ideas that lie between them.

Excerpt from "Several Rooms of Flashing Lights (Randy)", Trevor King.

Can you talk about your Notions series and its relationship to this solo show?

TK: Thanks for asking this, because it’s really important to me. I think that this relationship can be slightly difficult to see because the works don’t always look similar, but they’re motivated by the same creative practice.

Throughout this show, you see objects from the landscape that I grew up in, and meet different characters from my personal life. The Notions series, which is a series of ceramic sculptures based on drawings that my grandfather made for me, is a deep dive into the same type of exchange or collaboration that drives my work. The Notions project is not all that different from Several Rooms of Flashing Lights – they’re both open-ended pursuits that reflect on my relationships with family to create objects that tell stories about our shared world.

I deeply enjoy that even though some of the content emerges from personal stories or relationships, you seem to really want to include everyone in your viewership. For example, I have never met Randy, but I love him. I have never met your grandfather, but can feel his warmth and influence on you. How do you do this? How do you get us strangers to feel a closeness with the people in your family through your artwork?

TK: I’m not sure, but I am glad that you feel this way.

I think that when we see people in their truest nature, it’s easy to appreciate them. The drawings from my grandfather that the Notions pieces are based on are a good example of this. While his hand didn’t have much experience drawing, I believe he was very comfortable and unselfconscious in making them, and so there is a transference that takes place. The drawings relay some wonderful playful aspect of his spirit.

I don’t think that I could make these multichannel video pieces about Randy if we didn’t have our interpersonal bond. There is a lot of trust there, and that allows me to record him as he really is.

Also, I think that part of the mechanism of portraiture is that these people sort’ve remain as strangers. These works that I’m making are not full biographies, and they’re not attempting to be, though there is a vastness that I’m interested in, in all of these pieces. Mostly, I’m trying to look at the creations that these people have made, their sort’ve creative responses to the circumstances of life. I think that gives us a middle ground to think about, and a larger reflection on how art making and self expression is essential for the soul.

When reading your exhibition statement, I came across what I think is a typo that I find really beautiful. At the end of the statement, you mention your faith in art’s capacity for giving us a place to “face down our deepest our fears.” I imagine that the line is supposed to say a place to “face our deepest of fears.” The typo re-enlivens the phrase for me and makes me really confront myself, how I am connected to people, and that we all are both limited and set free by our mortality. This is a concept I see again and again in the work, and that is perhaps written subconsciously in this typo. How does mortality—the state of being subject to death—inform the work?

TK: You know, I think I’ve always had this low level existential dread permeating through who I am. Honestly, I remember being a kid and laying in bed tormented by the feeling that time was passing too quickly. The fear that was probably on my mind when I wrote the text for the show is probably the fear of being ineffective in communicating the profound beauty of daily life. I think that my art making is a way of looking at the things I care about and trying to create something that honors and appreciates them. The Enormous Room is a good example of that, where I was looking at this worrisome moment, but trying to find something serene and life affirming within it.

I keep thinking about that moment when we were touring the exhibition, and we looked at those small ceramic sculptures. At the time,I said they’re reminiscent of ancient amphitheaters or perhaps a dilapidated James Turrell Skyspace. It's haunting for me to think about that, but probably inevitable. Art is such a delicate and precious thing. I hope that the works that I’m making distill the magnitude of the present.

Space is Not Enough is on view at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania through March 1, 2024.