Published August 3, 2022

Ways of Viewing Art

There is no right or wrong way to view an artwork. While the artist will have specific intentions that they wish to express, the viewer's own experience and interpretation brings a perspective equally as important. This perspective exists outside of both the art object and the artist. Due to this open-endedness, which generally differs from the more common narrative structure of a novel or movie, the experience of interpreting a work of art can seem intimidating. This feeling is exacerbated for a viewer who is experiencing an artist’s work for the first time or who isn’t as knowledgeable of the work’s context within art history.

A primary goal of art is to expand the definition of what art can be; the definition is never fixed. Therefore, work tends to respond not only to the time in which it was made but also to the work that came before. For the casual viewer, the amount of prior history necessary for a more nuanced understanding can feel daunting. However, there are many other ways to approach viewing a work of art.

One way to begin viewing an artwork is to understand that the work has both form and content. Although these two categories can be separated for simplified definition, both parts are integral to the reading of the work. Observations on form relate to the work's physical characteristics and ask questions such as whether the work exists as an image, an object, a text, or a medium that unfolds over time. These styles generally comprise our understanding of the development of Modernism in art. During this period, artists focused on medium specificity and pushed the language of their chosen materials to a place they considered their own.

Content relates to the artist’s intentions and personal significance in making the work. Content also incorporates the potential implications of the work for the viewer and how it makes them feel. This aspect of the work will change over time depending on the viewer's own individual feelings, the viewer’s relationship with the period in which it was made, and the contemporary climate when the work is viewed.

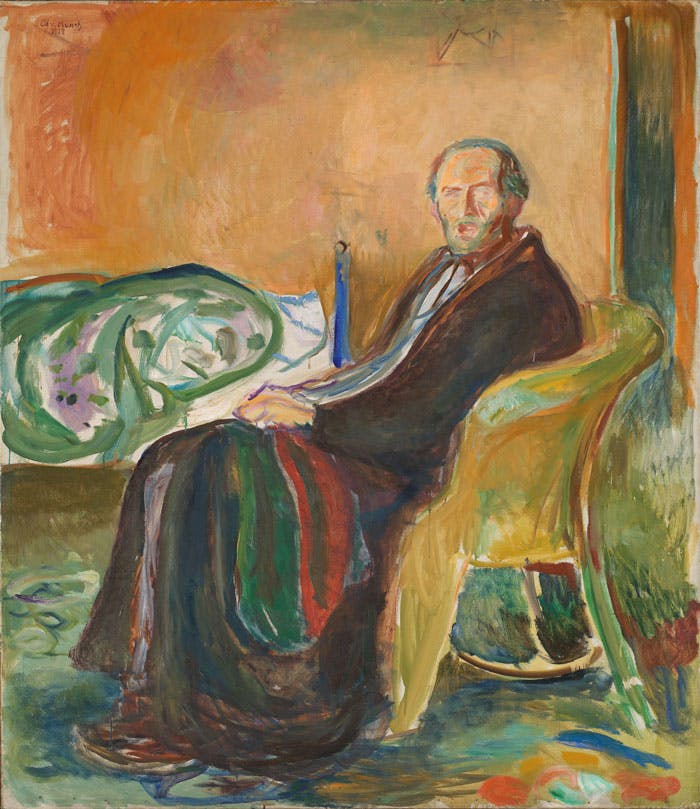

For example, during the 1918 influenza pandemic artists were forced to deal not only with the fear of contracting the virus but also the potential of death. This sense of despair and uncertainty during a pandemic can be seen again in much of the art made during the lockdown due to COVID-19. As history repeats itself, we can use art as a tool to comprehend and connect with the past as it relates to the present.

Because seeing comes before language, there is a tendency to respond to the visual arts in a way that undervalues the text that accompanies and supports a work. Reliance on passively viewing with our eyes can promote a reading that can feel very surface level. For the viewer who desires a deeper understanding of a work of art, the accompanying text offers additional insight into the artist’s intentions.

When thinking about language in relation to an artwork, the title of the piece is generally the best place to start. Depending on the style, the title may be the only part of the artwork that exists literally. For an abstract work of art, the title can help the viewer understand if the work is meant to be read as poetic, process-based, or conceptual. Consider the different associations that occur between these three titles: Grey Fireworks vs Untitled vs Who is Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue. Titles provide a starting point for one potential way to view the piece.

Outside of the title, the listed materials are also an excellent resource for understanding an artist's point of view. For most artists, the medium is also the message, and these two aspects can’t truly be separated. There is generally an instinctual or conceptual reason that artists choose to work with a specific medium.

For artworks that came during and after the rise of Postmodernism, the materials that make up an artwork are only limited by the choice of the artist. Artists are freed from their reliance on limited materiality (oil paint, ceramic, stone, wood). Now, artists can access the seemingly infinite number of materials that form our world: organic materials that change over time, recontextualized cultural artifacts, digital algorithms, etc. With that freedom, artists are able to better articulate their own specific intentions and experience.

As an example, one of the artists we feature on our platform is Susan Stainman. Her practice deconstructs many of the preconceived notions about the role of an artwork and opens the potential for new ways of thinking about and experiencing art. Excluding the decorative arts and architecture, most of the history of fine art is built around the concept of a singular creator making an image or object with the sole intention for it to be experienced visually.

Portable Bench for Lingering Conversations challenges this limitation by creating a space for the viewers to engage the work. The viewers activate the work by sitting on it and connecting with both the object physically and the other viewer. Therefore, viewers play an essential role in this artwork as they engage both physically and emotionally through the use of the piece. Additionally, by allowing viewers to carry the piece on their back, the artwork can be activated anywhere including a public setting. This challenges the idea that artwork can only be appreciated within an exhibition space.

In our age of globalization, art exists to question the singular narratives that many have accepted as “the truth.” However, our world is made up of countless voices, experiences, and perspectives. Art materializes these infinite experiences and erodes the concept that any one position could ever contain everyone's truth. As our culture continues to change at an unprecedented pace so must our art, the viewer learns from the artist as the artist learns from the viewer.

Additional Resources

Ad Reinhardt, How to Look, 1947

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation, 1966

Joseph Kosuth, Art After Philosophy, 1969

John Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972

Thomas McEvilly, Heads It’s Form, Tails It’s Not Content, 1982

Andrea Fraser, Why Does Fred Sandback’s Work Make Me Cry, 2005