Published August 12, 2022

Creation, Collaboration, & Resilience: Interview with Yo-Yo Lin

Yo-Yo Lin is a Taiwanese-American, interdisciplinary artist working with animation, dance, and performance. Her works often incorporate all three mediums to explore the bodily experiences of living with chronic illness and to establish possibilities for self-knowledge through a collaborative practice.

In July, Lin held a multisensory performance, channels, as a 2020 Open Call recipient at The Shed, the new—and large—cultural institution and venue in Hudson Yards. She taught at NYU Tisch ITP/IMA as the 2021 Red Burns Fellow and was recently awarded a 2022 Disability Futures Fellowship. Her work has been featured in NOWNESS, Art in America, and Surface magazine. Born and raised in Los Angeles, she now lives in Sunset Park in Brooklyn.

I met Yo-Yo in Taipei two years ago. We bonded over our shared love for Rilakkuma and gushed about Ratatouille the Musical, among many other things. In 2021, I contributed as a translator to Yo-Yo’s bilingual performance film, Re:collections, a project she made during her four-month visit to Taiwan. We caught up in July to talk about her recent commission and her evolving practice.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Congratulations on channels! Was it your biggest commission yet? What was it like working with a major institution to develop a project at that scale?

Lin: Yes, thank you! This was the biggest commission I had ever received, which made it a daunting process.

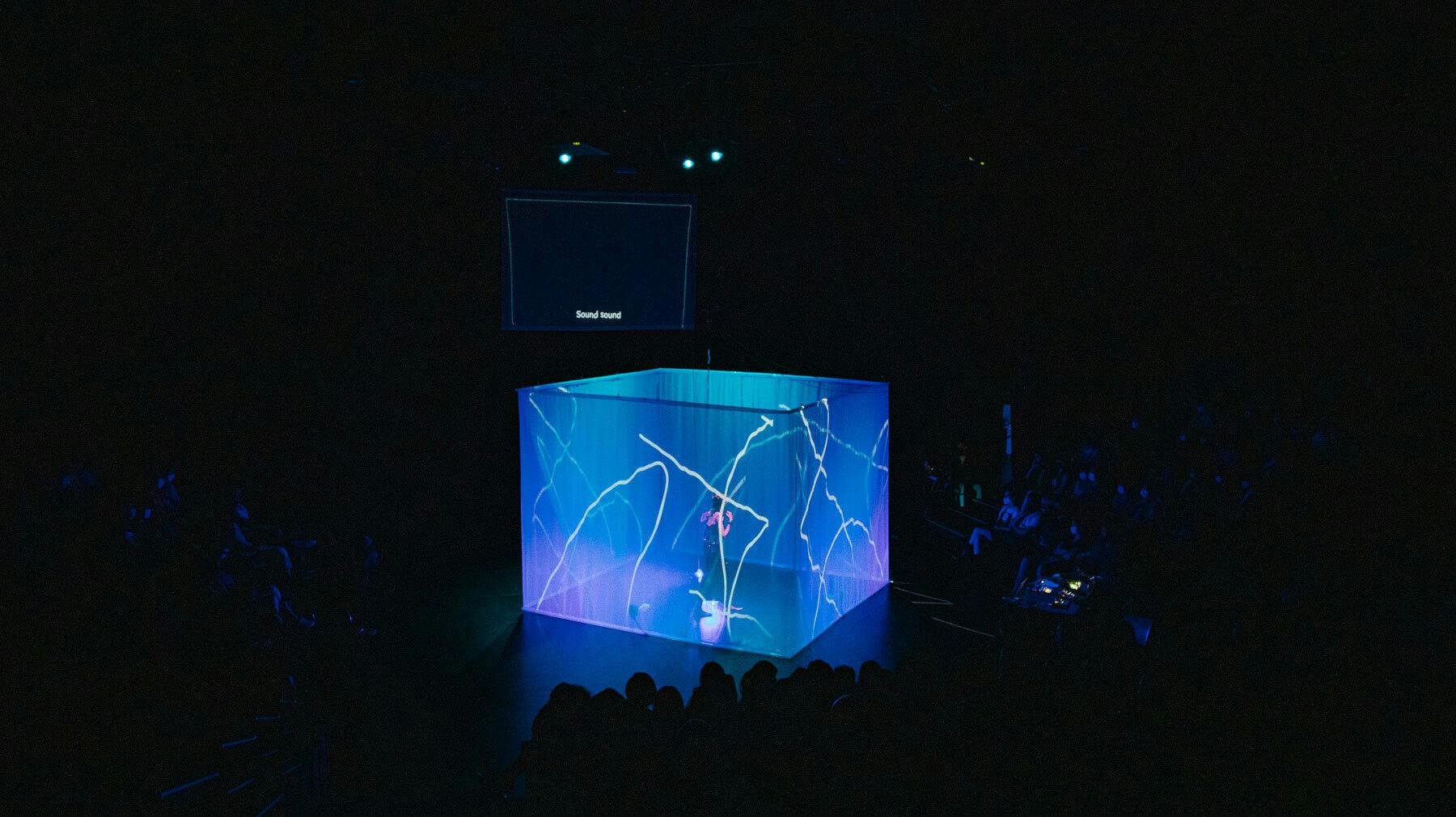

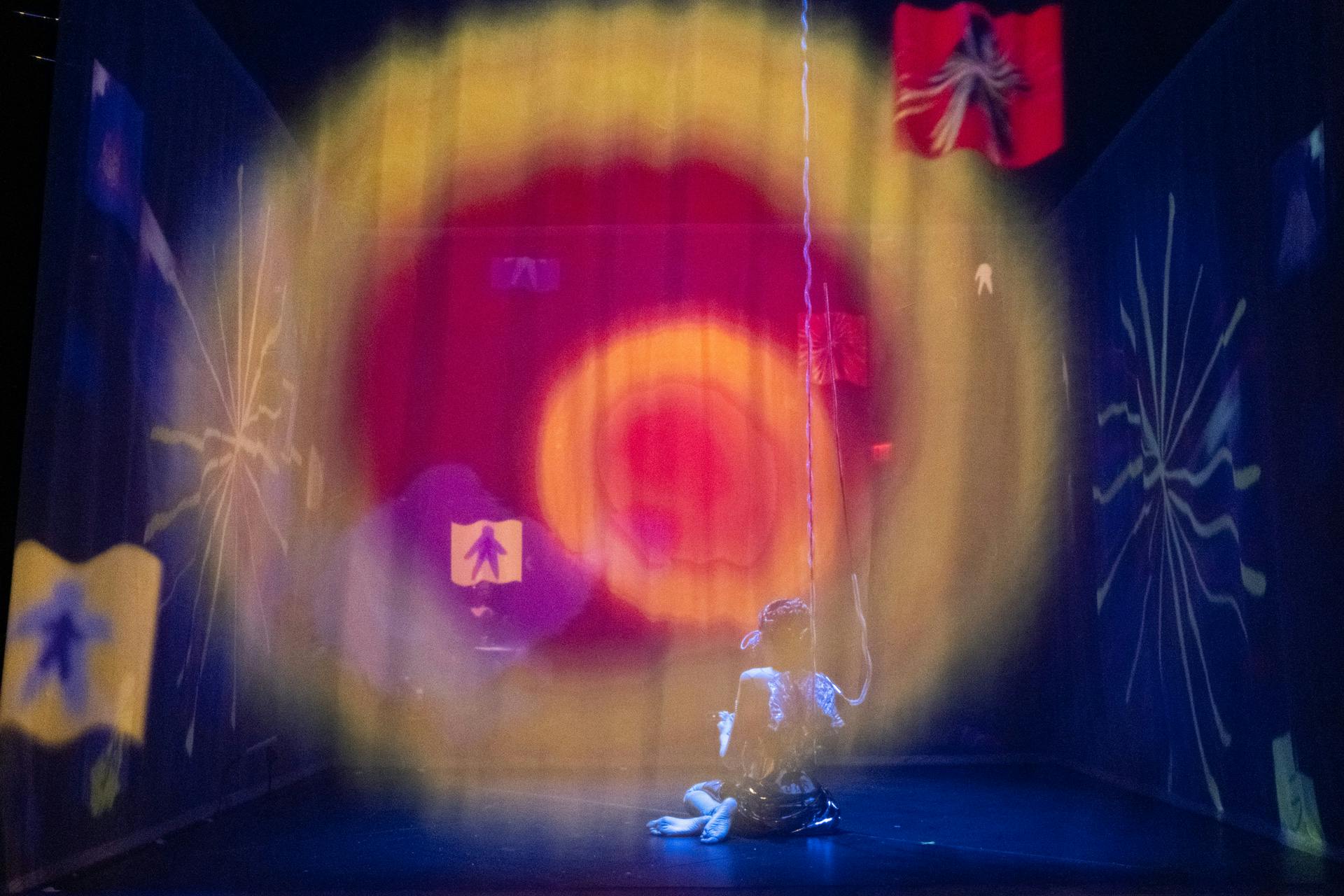

When I make installations and performances, they’re made to fit into the space they’re shown in. Showing inside the 500-seat Griffin Theater meant that I had to enlarge my work in every way. The projections expanded from 2 to 4 screens, and the music expanded into surround sound. Things were still coming together the day of… literally right before the first performance!

It was important for me to design the show for people to feel closer to each other, and create a space that centered access. We had pillows, wheelchair seating, and our U-shaped seating created a more intimate relationship with me as the performer. The Shed was helpful in figuring this out with us.

But the production process was very intense. It was hard on the body. I’m still recovering.

What I hope to do is create spaces for people to experience a part of themselves that they’ve forgotten or have yet to discover. That’s always been a key part of my work: to create stories for a deeper self-knowledge.

I can imagine! How did you prepare for such a demanding project?

Lin: That’s a good question, and a hard one, because this performance of the body—my body—is the work. And unfortunately, my chronically ill body is not reliable. There is always the chance my body would refuse to perform. That was a reality we, as a team, had to acknowledge and adjust for.

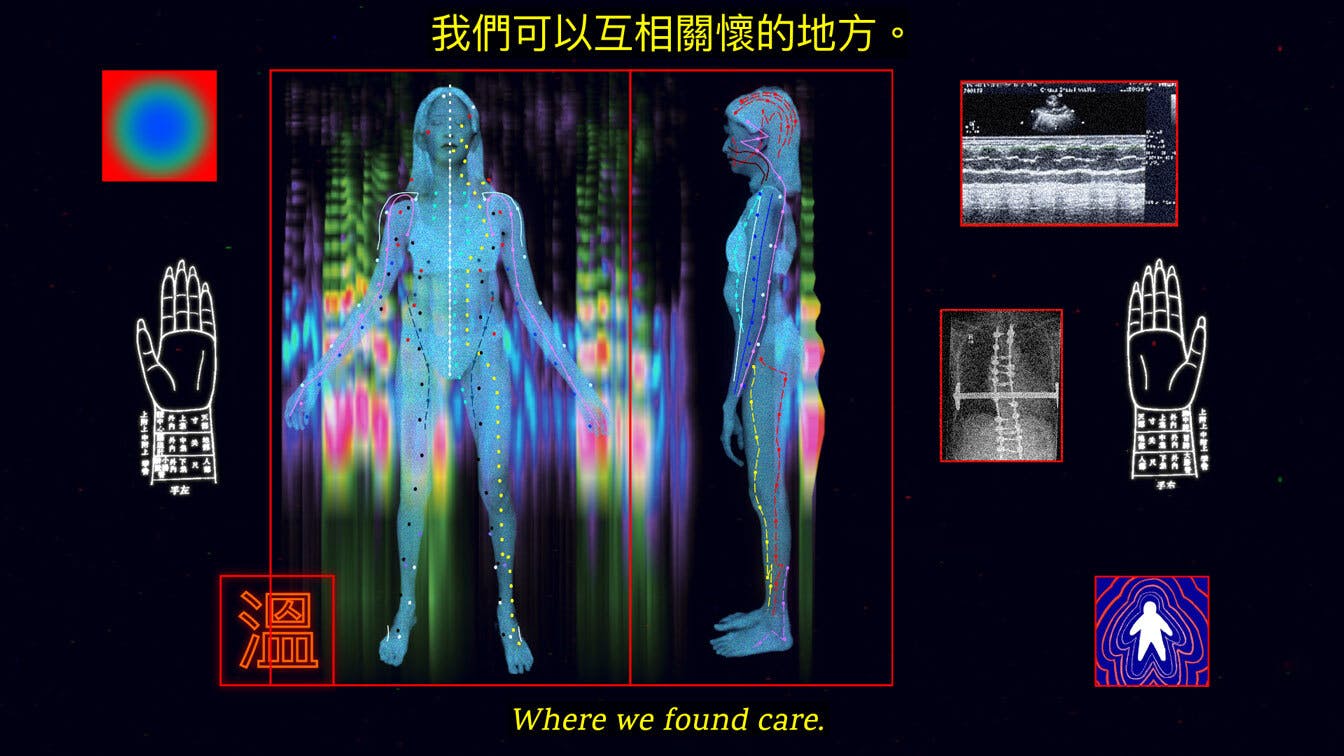

My long-term collaboration with musician Despina (Mica Matchen) is actually based on listening to the body, both literally and figuratively. We developed a process of attaching microphones to my body to capture the sounds of my bones and joints as I danced, and Mica would sample and synthesize the creaking and crackling sounds of my connective tissue disorder into a music score in real-time. The music would be different based on my bodily condition at the time. This created a generative framework where we could both explore and engage with the process at different capacities.

Back to your question, I think it’s about finding ways to meet each other where we were at, and building in the process of care in the way we create work.

That, and having our creative producer, David Lee Sierra taking care of us during production. I also did acupuncture weekly, and my partner helped a lot with chores and errands. There was a lot of involved labor that often goes unacknowledged.

Indeed, and I love how you always ensure to credit all your contributors publicly, because it really takes a village! Besides Mica, you also collaborated with artist Pelenakeke Brown and designer Weijing Xiao for channels. How did these collaborations come about?

Lin: I met Pelenekeke through the NYC disability arts community and we became friends and collaborators working with dance and technology. When the pandemic arrived, we became separated. Keke moved back to Aotearoa and we spent a lot of time communicating remotely. In 2020, we founded ROTATIONS, an online workshop space focusing on artistry, disability, and access. It was a way for disabled community to continue to be together and dance together over the web. We wanted to allude to that remote togetherness in channels, so Pelenakeke beamed-in live from her living room in New Zealand. Through the brilliance of our graphics artist Torin Blankensmith, Keke emerged as a projection silhouette, and we danced together through describing our movements (audio description). We also showed her live drawings on projection screens through an app by Avneesh Sarwate, which played with presence and expanded ideas of what dance performance can be.

I was introduced to Weijing Xiao through Torin, and reached out to them after seeing their work on Instagram. They make cool “post-human couture” with cyborgian inspirations. When I was more visibly disabled, I would tell people I was a cyborg. When we started attaching mics onto my body, it felt strangely familiar, being attached to tubes and wires. In some ways, the cyborg makes disability more palatable to the nondisabled public. Commissioning Weijing to make my garment was a way of reclaiming this cyborg figure for myself, situating the cyborg as not just a feminist, queer figure but also a disabled, crip figure.

I think it’s so important to acknowledge collaborative efforts and to be transparent about them! In what ways does collaboration ground and inform your practice?

Lin: Almost every project I do is a collaboration. I think that’s why my practice has shifted from painting to performance, film, and socially-engaged works, because the process is always tied to working with and witnessing and being with others. The work is the shared making of the work.

Maybe it’s also because I grew up in a large family, so I try to find ways for everyone to be involved!

I’ve been learning how to change how we present these works; I don’t attribute the work to one name but talk about it as work that belongs to many.

So how did you go from painting, a relatively less collaborative medium, to animation and video, and then to performance?

Lin: Painting is solitary work. I remember being so sad and lonely—I was yearning for a different kind of process! That’s when I started bringing projection and sound to my paintings and drawings, creating animated painting installations.

My work became more time-based. That involved setting up spaces to view it and inviting people to engage and experience the work in self-directed ways. I was drawn to creating shared experiences that also gave viewers space to engage in their own internal realm of thought. I started creating more non-linear film installations, incorporating immersive sound, and that led to working with live performers. My performance practice emerged once I started creating work about my experience with illness.

Yo-Yo Lin, Timelapse of the May Resilience Journal spread- a circle on the right page slowly filling up slice by slice with green hues. Music by David Britton, sampling the sounds of my body and processing the sounds with a synthesizer. Courtesy of the artist.

You co-founded the creative production company THE FAMILY in 2016 and then ROTATIONS, a very different, non-commercial, type of partnership a few years later. When did you decide to move away from the commercial realm and to create works that speak to your experience of living with chronic illness?

Lin: Yes, I worked at the production company as the art director. After 3 years, I realized I wasn’t particularly interested in commercial work. I started speaking more openly about my experience with illness around 2019 during my “Access” Artist Residency at EYEBEAM. The project I proposed was creating artistic methodologies and frameworks for reclaiming chronic health trauma.

It stemmed from a very personal, private place, where I realized we don’t put language to pain. I had no idea what I was doing because there was no roadmap. But I began to do tons of research, had many conversations with ill and disabled communities, and built datasets tracking the ways my chronic illness presents itself in daily life. This resulted in the Resilience Journal, a publication and collective tool to visualize and honor complex bodily experiences. We’ve sold about 500 copies since the first edition release in 2019!

Wow! What have been some challenges of working in this space? Or perhaps pressures of “representing” the disability community? You were awarded a 2022 Disability Futures Fellowship recently, and when you shared the exciting news on Instagram, you thanked the disability community for their trust.

Yea, trust is huge. I have been disabled my whole life, but I came into disability culture only a few years ago, around the time of creating the Resilience Journal. It’s important to make this distinction: not all who are disabled identify with the culture. It’s a complex community—an ecology that encompasses a multitude of experiences.

Being awarded with that funding is humbling, because I feel my work sits on the shoulders of so many disabled activists, scholars, and storytellers. It reaffirmed my work and engagement with the community in a way. I really look forward to using this funding for future collaborations.

Speaking of representation, as an Asian American, specifically Taiwanese-American, you also belong to this particular diasporic space. Your video piece Re:collections explores some of this in relation to intergenerational trauma. In what ways does your cultural identity influence your creative approach and process?

Lin: Yes, that took more of a forefront with Re:collections. Growing up in a Taoist-Buddhist family, it was imbued in me from a young age that this lifetime is among one of many. It’s an understanding of reincarnation and karmic response, where energy is neither created nor destroyed.

I think about that a lot when I make work: what am I putting out into the world? What are the energies that I like creating? What are the spaces I’m creating to bring people into?

So much of how we think film and animation should work doesn't really align with my aesthetic and temporal values. I love making experimental, immersive, multi-channel films that are nonlinear, cyclical, and without a set beginning or end: wherever you arrived is where you began.

What I hope to do is create spaces for people to experience a part of themselves that they’ve forgotten or have yet to discover. That’s always been a key part of my work: to create stories for a deeper self-knowledge. I think that’s a very Buddhist thing. My experience with cultural heritage is within this context of spiritual practice, and the diasporic aspect of it comes from only having some access to that in certain contexts.

There’s always a sense of trying to get closer to myself in all my works, and I think that’s what I try to do with my cultural heritage as well. Dance brings me closer to this spiritual space.

How do you see your practice evolving? What are some topics you’re excited about exploring next?

Lin: I’m excited to keep developing the Resilience Journal and to finish a piece called Blue Tears, which is about bioluminescence, the ocean, the climate, and technology.

There’s a chance that I’ll be doing more performance works that don’t involve the same physicality. As much as I love performance, it became apparent after channels that the intensive process becomes risky for me in the ways that I expend energy. It’s just not sustainable for me in this body, so I might look for digital means to create movement and dance works without the physical “transaction” that it requires. I’m excited about leaning into other mediums, that’s the joy of being an interdisciplinary artist!

I’ve also been trying to embrace “fun” recently, because so much of my practice moves through intense experiences. Can there be a sense of fun in the process of making these works? Can engagement with something intimate or traumatic also be expansive and pleasurable, transforming what that experience was?

Thinking about how to transform energies is interesting to me these days. How do I begin with this experience, observe it, play with it, then reveal it in a different space and context?

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!