Published August 15, 2023

Between a Storefront and a Mini-Mall, Two Visions of Asian American Art

This summer, Asian diasporic art is seemingly everywhere. In New York alone, major institutions are presenting solo shows of Sarah Sze, Josh Kline, Oscar yi Hou, and Mire Lee. The “vaguely Asian” fashion collective CFGNY has taken over the basement of SculptureCenter, while a gathering of 45 “Asianish” artists is on view at two galleries in Brooklyn. As these qualifiers suggest, it is hard to be confident in the category of Asian American art, to vouch for its aesthetic or political coherence. All the same, the collective nature of these projects suggests that “Asian American” must be more than a consumer category or an individualistic marker of identity. Since the term’s inception amid the activist tumult of the 1960s, Asian Americans have continually queried its capacity to actively forge (rather than merely describe) a community – a project destined to oscillate perpetually between hope and disappointment.

Two of the season’s most concise and provocative explorations of Asian American community take place in nontraditional spaces. The first is “Home-o-Stasis,” an exhibition inconspicuously installed in the hallway of a mini-mall in Flushing. The show reflects on the neighborhood’s history of displacement while honoring the home it’s been – however temporary or provisional – to the Asian immigrants who live and work there.

On the mall’s external window on Kissena Blvd, a sentimental message is posted among advertisements for short-term rooms and subdivided apartments. In shaky Chinese characters, it’s written: 最爱你的人是我. The person who loves you most is me. A documentation image is posted next to it: a hand (presumably that of the artist, Xueli Wang) putting up the notice. Another photograph looks over the shoulder of an onlooker, documenting the project’s reception. Is he wondering about the misplaced love note, or simply looking for a place to stay? When I was standing in his place, a woman approached me and asked me in Mandarin whether I was looking for housing. I said I was looking at art, and she moved on.

While there are those (like me) who visited the mall for the first time to view the show, I imagine that most of its audience is made up of mall regulars: people on their way to the butcher or the barber, workers on the job, or new arrivals looking for a place to live. Herb Tam and Lu Zhang, who organized the show and contributed their own artwork, frame it as “offerings to those seeking housing.” They draw a connection between formal (and institutionally sanctified) artmaking and daily practices of decoration and homemaking among immigrants. Zhang’s ceramic cellphone, for instance, is flanked by artificial flowers from a nearby 99 cent shop. And in auspicious shades of red, two works hang above the bustle of daily commerce: a paper-cut by Xiyadie renders a neighborhood clock tower within the shape of a butterfly, while Anne Wu shows a Chinese calendar with the days and months excised, a delicate tribute to the passage of time in a place that may or may not be home.

While it is attentive to the precarious lives of many of the neighborhood’s residents, Home-o-Stasis has a nostalgic slant: a posted sheet of paper invites viewers to share memories of bygone restaurants and life’s great lessons.

A second exhibition on view this summer offers a different vision of Asian American community: similarly personal, but inextricably entwined with histories of organizing and agitation. The show, titled Just Between Us, is drawn from the archive of the painter Arlan Huang. It takes place in the back gallery of Pearl River Mart, the longtime Asian business in Soho.

Just Between Us includes little of Huang’s own artwork. Instead, a portrait of the individual emerges through his relationships with others. These are bonds of friendship and solidarity rather than commerce: much of the material on view entered Huang’s collection through swaps with other artists. Some, like Sol LeWitt, were people who Huang met through his longtime framing business, Squid Frames. Others were fellow organizers in two important Asian American art and activist collectives, Basement Workshop and Godzilla. One can imagine a shadow archive of Huang’s own work: all the works he traded for the ones on view in the show.

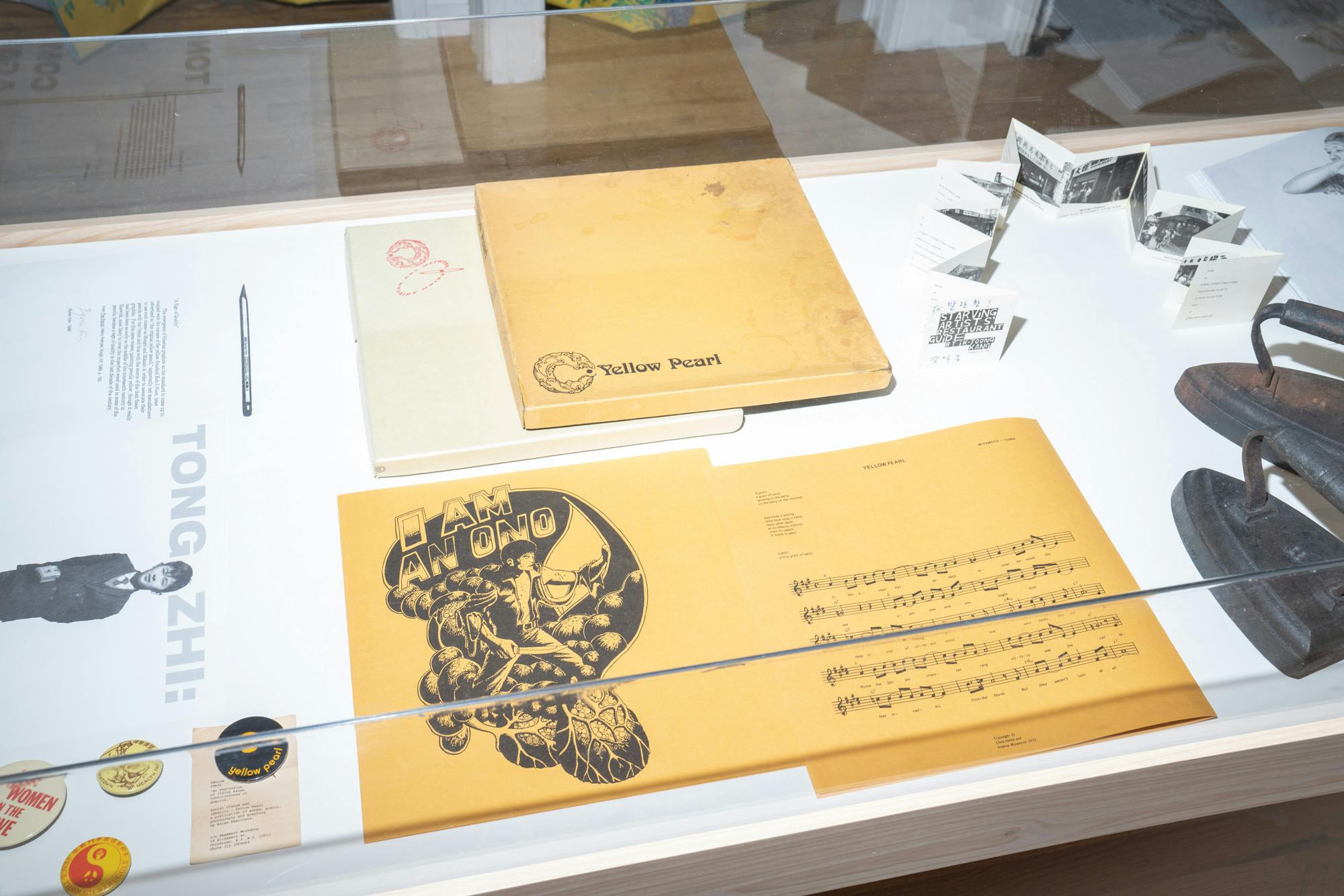

Echoing its title, the work in Just Between Us is hung close together in the gallery. Much of it is small in format and extends from the category of art into ephemera, publications, and memorabilia. There are archival images from Basement Workshop and other records of the Third World internationalist spirit of the 1970s: a photograph of a march; gorgeous posters for African Liberation Day and a street fair in Chinatown. Anyone familiar with Godzilla – the coalition that pushed for greater inclusion of Asian American artists in the 1990s – will also recognize pieces by members of the group, including Tomie Arai, Byron Kim, and Ken Chu. Some of the show’s highlights sit in a vitrine, including Yellow Pearl, a 1972 boxed collection of songs and other printed materials by Basement Workshop, and a 1996 accordion zine by Yik-Joong Kang called Starving Artists’ Restaurant Guide.

But many of the works in the show address the formal histories of Asian American art more obliquely, if at all. In one corner, for instance, a starry lithograph by Tomomi Ono beautifully complements a watercolor by Kazuko Miyamoto, whose concentric circles recall the rings of a tree trunk. Histories of affiliation and organization blend into the more informal registers of friendship, gossip, and complaint. Huang’s collection – like all collections – reflects idiosyncrasies of taste and chance as well as lasting relationships and commitments. The story behind each work is not spelled out: rather than a legible map of allegiances, it offers a cumulative window into decades of life, work, and activism. In a catalog interview with Howie Chen, one of the show’s curators, Huang speaks about the uncertainty of reconciling his painting practice and his radical politics. “Decolonizing my formal art training is a hard thing to do. In this unpacking process there are moments of brilliant clarity, and I see through Asian American eyes,” he says. “Sometimes the pieces fit, sometimes not.”

Just Between Us does not offer an answer to this puzzle, nor a unified vision of Asian American aesthetics, but it does offer a multiplicity of pieces. When considered alongside Home-o-Stasis, it’s hard not to think back to a recent dispute about the responsibilities of Asian American artists and institutions. In 2021, Huang was one of nineteen Godzilla members to withdraw from Tam’s retrospective of the collective at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA), which responded by canceling the exhibition. The museum was implicated in the city’s plan to construct a new jail in Chinatown, a plan opposed by prison abolitionist and anti-gentrification organizers. Huang was an early voice of questioning and dissent, and as curator Danielle Wu recounts in her catalog essay, Just Between Us was “conceptualized almost as a retaliation” to MOCA. There are lessons to be learned from this confrontation – and from the contrasting approaches of the two projects that follow in its wake.

The similarities are not lost on me. Together, Just Between Us and Home-o-Stasis beautifully stage art’s dissolution into daily routines of living, working, and communing. Both are moving tributes to the aesthetic practices of Asian diasporic people, which often take place in a minor key: that is, at small scales, with modest resources, and within domestic spaces. Neither project is a commercial venture and both are clearly labors of love. But the siting of both exhibitions within Asian businesses signals unresolved questions about the status of “Asian American” as a consumer category and “Asian American art” as a consumable aesthetic. As the example of MOCA demonstrates, there is nothing inherently good or innocent about “Asian” spaces: they can be sites of exploitation and silencing, just as they can be places to gather and remember.

For all of its poignancy, Home-o-Stasis risks indulging this myth of innocence. Arlan Huang’s archive, in contrast, reminds us that Asian American art has always been entwined with Third World and anticapitalist consciousness. If there is to be any hope for “Asian American art,” it should honor his example and remain alert for moments when friendship must deepen into solidarity. An art that fights against jails, in short, also fights for life.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!