Published January 26, 2023

Carlos Rosales-Silva on Constraints & Community

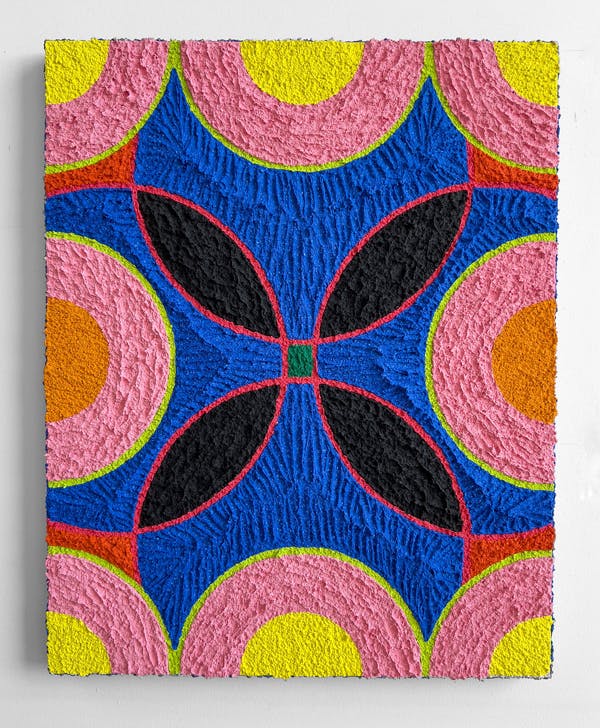

Carlos Rosales-Silva is an artist and educator who lives between New York and Texas. He makes bold sculptures, paintings and installations that reflect on the vernacular culture of the American Southwest, where he grew up. Rosales-Silva’s work mines his rich cultural heritage as a Mexican and Indigenous artist, as well as calling attention to the freedom and insidious influences of colonialism and contemporary capitalism.

Carlos and I talked about the deep and lasting impact of his El Paso upbringing on his practice, the joys and challenges of making a living as an artist in NYC, and the relationship between his commissioned projects and studio practice. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What are you working on right now?

CRS: Right now I'm in the studio making work for my solo show at Sargent’s Daughters in Los Angeles. They already have a gallery here in NYC – downtown, on East Broadway – and in February they're opening a new space in LA. They'll open with a big group show, and then I'll have my solo show at the end of March, early April.

So for the last couple of months I’ve been trying to get to the point where I’m making ‘good’ work! I'm full-time in the studio right now, which is so nice; I've had a few corporate commissions this year, which have enabled me to do that. For me, the dream in the studio is to feel free enough to make bad work, while having the deadlines to make the tried and tested pieces that will keep the studio afloat. It's been fun; luckily I've had the time and the resources to just push the work in some fun directions. I feel like the crucial thing is being able to give yourself room to flop!

Just to take a few steps back and introduce your practice for those who don’t know it, can you say a bit more about how it's influenced by the American Southwest – visually and conceptually?

CRS: Sure. I think in the most basic way it's influenced directly by the people I grew up around. In retrospect, I realize I was lucky enough to grow up around super creative people; all of my aunts and uncles were either fabricators, craftspeople or musicians.

I grew up in a house with this huge, newly immigrated family to the United States in a city called El Paso, which is on the border of the US and Mexico and is also indigenous tribal land. So there was this confluence of all of these cultures. We were embedded into the culture as well and very resourceful and crafty. We had to be to survive. Now I see that growing up in that environment was such a blessing because everything around me was handmade, or painted by hand. I was surrounded by ingenious solutions to everyday problems; my grandfather was this master welder who made so many of the objects and furniture in my grandmother's house, which is where I grew up for a large portion of my life.

Similarly, my uncles were either builders or contractors working on construction sites, building homes. I also lived in a neighborhood that was covered in murals that were painted by local people; this extended not only to commercial murals and business signs but also spilled over into murals that were telling the story of the neighborhood.

I was also heavily exposed to what’s usually referred to as Chicano arts, which is art, culture and tradition produced by newly immigrated Mexican Americans.

My family, hypervisual environment, and neighborhood, which served as a locus point for so many cultural influences, soaked into my very being and now underpins everything I create.

When I went to college in a bigger city in Texas, I gained some important critical distance, and I revisited the American Southwest of my upbringing with the intent to research it. The El Paso region is one of several sites in North America where a very specific version of Spanish colonialism happened. There are architectural echoes of Spanish colonial buildings that exist and are really unique to that area – West Texas, Arizona, New Mexico – that have this vernacular that is so fascinating.The architectural style has been so influential, not only to the region but on modernism as a whole.

For example, very square buildings which would then be echoed by square modernist buildings are actually omnipresent throughout the history of that region. In turn, those structures themselves echoed the mud brick buildings of the indigenous people, which were then covered in sand and lime. This is all information I wasn’t aware of until I started diving into the history of the area. It provides the bedrock for the work in a lot of ways. My research extends across historical, visual and cultural interests and results in this abstract stew.

I feel as if what you’re describing is a deep-rooted connection to your influences and references that’s crucial to your work’s success. If an artist who didn’t have your background tried to come in, quote the local vernacular of the Southwest and visually reference the cultural influences you’re talking about, their work simply wouldn’t ring true in the same way yours does. There’s an unfakeable authenticity there, for me…

CRS: It’s an authenticity that results in what I’d almost describe as an obsession –that's how it feels to me; a fascination with the elements of something and how it's made, and then the history of how that thing came to be. I think that’s the work of an artist: all of us are researchers who are obsessed not just with the work but also with what goes into the work.

What really comes through is your lively, rigorous interest in material culture. On a related note, your considered use of texture is something that immediately jumps out at the viewer on a purely visual level. However, given your personal history and research into the history of southwestern architecture, it’s clarified for me even more….

CRS: Totally, I think that was instinctual; it’s something that I was drawn to before I even knew the source for it. It wasn't until I gained some distance and went back and that I realized, “Oh, every wall here is textured. The ground is textured with sand and stone, and I grew up around mountains.” The same is true of my use of color: some traditional Mexican painted buildings are incredibly bright and saturated with color, and I was drawn to that out of instinct.

Constraints are crucial. Every artist is constrained by the possibilities of their materials – we know we can push them and experiment with them, but ultimately there’s a constraint to each process. Within those constraints, you’re liberated.

Do you think of your work as political?

CRS: I think that for me, I can't expect my paintings to be inherently political. That seems a lot of labor to expect for a painting to do on its own!

But I will say that I do a lot of political work surrounding my practice. Also, sometimes simply positioning these works as paintings feels somewhat political. Within the history of painting, my work inevitably occupies a political position. It was not one that I chose, but one that just emerged. To me, being a political artist manifests in so many different ways other than paintings.

Well, you've got a lot of strings to your bow, haven't you? You've curated as well….

CRS: Sure. I would use that term loosely only because I highly respect the work of curators…

Maybe ‘organizing shows’ is a better way to put it?

CRS: I’d say my work is more about sharing access to whatever spaces I have, really more of a resource sharing practice.

That brings me to my next question about Beverly’s – the artist-run space/bar/community hub in which you’re involved. Can you say more about that?

CRS: Beverly’s is so interesting because it started off as a bar and exhibition space downtown that was around for almost a decade. It was forced to close because of the pandemic, but after lockdown it became a curatorial project that was run by and large by an artist named Leah Dixon, who was one of the original partners and founders. Now it’s morphed into a project and installation-driven space and service establishment that’s run by a collective of artists, with Leah at its helm – she’s just an incredible curator and artist herself. I feel really lucky to be a part of something collective, something communal outside my practice.

One of the hugely challenging things about living in New York, which I'm sure you know, is that it can be a rather isolating experience. As an artist, it can feel as if you're toiling away in your studio on your own. This is especially true if you didn’t go to grad school here, which I eventually did, or grow up in the city. That is why Beverly’s is so important in cultivating an arts community.

The artist Azikiwe Mohammed also runs a food bank out of Beverly’s temporary Eldridge Street space every two weeks that all of us volunteer at periodically, and it's also an occasional nightlife venue and community space. Beverly’s expanded its mission and is really driven by the people who were attracted to the project and brought into the fold by Leah. Fingers crossed, it seems like there is going to be a more permanent home for Beverly's on Grand Street, and it will again open as a bar/multi-use space, which is pretty exciting.

To me, Beverly’s encompasses all the stuff that’s crucial to exist and thrive as an artist in this city. There are so many kinds of art worlds that exist in NYC and so many of them are entangled with the marketplace unfortunately…

Absolutely. I find it much more brutally commercial here than London actually. The way you're describing Beverly’s – with its artist-run spirit and DIY ethos – makes me think slightly nostalgically about a lot of the artist-run spaces in London in the mid to late 00s…

CRS: I went to school in Austin, Texas, which doesn't have a market to speak of. Everything there was also artist driven. Everything was DIY – out of necessity more than anything.That same spirit attracted me to become involved with Beverly’s.

And yes, New York can be brutal because of the marketplace. I think it really leads to a lot of bad art and ruins a lot of people's practices. The marketplace can be very disillusioning, and can also encourage artists to make a lot of derivative art, which I can't imagine it's very fun to make either, to be honest.

What is more tragic to me is that it really destroys so many artists, because this myth of the market and the market star is rife. When it doesn't happen for an artist, (which is true for almost everyone), they will just stop making work.

I think the shame to me about New York is that it has this amazing history as a hotbed for artistic activity. In the seventies, eighties, nineties even, it was genuinely affordable and artists managed to stay afloat financially and make work. But now the amount of money you need to make in order to even live there is simply untenable for a lot of people, especially if you're trying to establish a practice.

CRS: Yeah. There have been so many times where I'll travel to another town for an exhibition and I'm just like, wow, you could really do a lot here.

You mean I don't have to find five grand a month just to tread water!?

CRS: Exactly.

You mentioned earlier you've undertaken some corporate commissions. How would you say your approach to those compares to your studio practice? What relationship do the two have, would you say?

CRS: I’ve worked on a lot more in the last year, and I’ve had projects that have run the gamut.

There have been projects where I'm commissioned to make six paintings, and they can be whatever I would like, which is wonderful. The works only need to be a certain scale. That's the constraint. There are also more collaborative projects with a specific prompt, and the content is decided by going back and forth. Lastly, there are some commissions in the middle. I propose certain things, and then we decide together the most promising approach for that particular project.

Constraints are key to these commissions: I might have either a physical constraint of size or space. I recently painted a mural for an elevator bank at the Empire State Building. It was obviously amazing to work there, but it also provided me with an amazing constraint: I had to work on two walls in a twenty foot corridor with twenty doors, ten on each side. It was unbelievable to have to deal with that much architecture! I was given an elevation drawing showing the available space that I could draw or paint within, and that’s very legible.

Constraints can be quite freeing, can't they?

CRS: Constraints are crucial. Every artist is constrained by the possibilities of their materials – we know we can push them and experiment with them, but ultimately there’s a constraint to each process. Within those constraints, you’re liberated, because you know exactly what’s possible if you’ve been thinking about and working with it for long enough.

The other thing about these commissions is that oftentimes, these are pieces that will exist in places that I will maybe only see once or twice after they’re finished. The people that commission a work are the ones who have to actually live with it, and I want them to be satisfied. I don’t want them to look at something that they absolutely hate every day, so obviously I take that into account and make something that’s often similar to a piece of mine they’ve already seen. They do not receive the intentional flops I make as part of my creative process in the studio, where I often try to make the opposite decision to get out of my comfort zone.

The only downside of these commissions is that they’re not going to bring about an exciting change in my practice. On the plus side, often the scale is bigger than I would get to make in a gallery, which can shift my perspective.

So some of these commissions do feed back into your work in the studio?

CRS: Yeah. Ultimately, I've been really happy with the commissions I’ve taken on. If we want to get into the nuts and bolts of the matter, the guaranteed income that comes from those projects is an important consideration.

Pragmatically speaking, I'm signing a contract which says I will get paid X amount of money by this day. That income allows me to work for three months on a solo show in Los Angeles and leaves me totally unencumbered with worrying about how I’m going to keep myself.

It’s actually very refreshing to speak to an artist who’s so open about the need for basic financial security! I wonder if more artists were open about the support they do or don’t receive – from family, partners, institutions – whether we could open up more important conversations about privilege in the art world more generally….

CRS: I agree! I try to be as open as possible with younger artists or peers about navigating the peaks and valleys of being a working artist. There is this pervasive myth of the genius that is starting to crumble a bit now which gives me some hope on that front. How many more “geniuses” would exist if everyone had access to economic security and nepotism?

I also think it is important for working artists to think of themselves as workers in an arts economy and align ourselves with labor and its push for more equitable conditions for all workers in our field. There is no arts economy without artists.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!