Published February 26, 2024

Documenting the Experience of Black Cowboys: A Conversation with Charles Lee

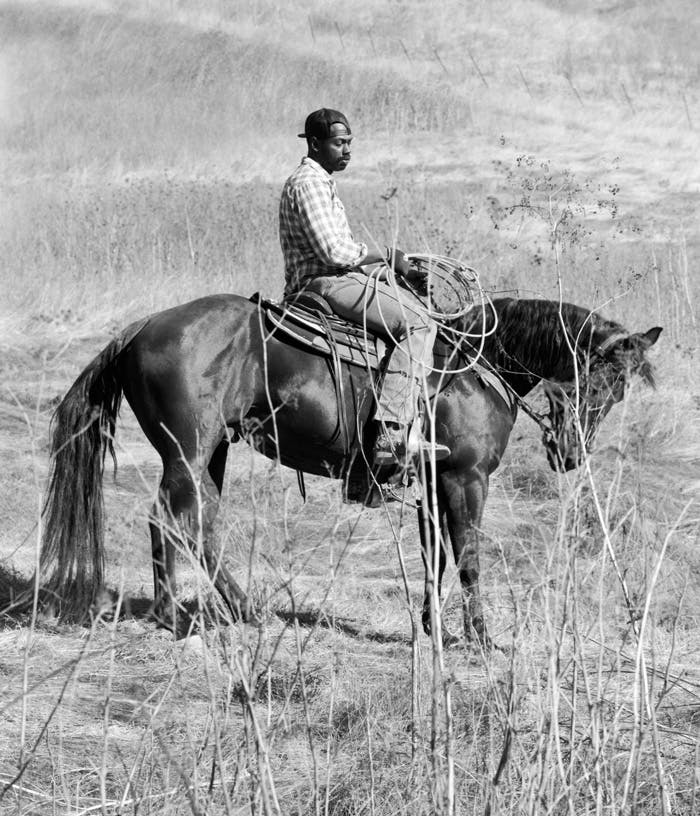

Photographer Charles Lee has his first solo show at SF Camerawork, sweat+dirt. It includes an installation with hay bales, a rocking chair, and a saddle as well as black and white photos of Black cowboys, cowhands, and ranchers in Louisiana, California’s Central Valley, and the Bay Area.

Lee grew up in California, and his family members were among the 300,000 people who came out to the Bay Area as part of the Great Migration (1910-1970) from the south. He recently graduated from California College of the Arts and now teaches there. After a successful, but unhappy career in sales, Lee became a professional artist.

Lee has an unwavering commitment to document the Black experience in the American West, which has a cultural history that long predates the archetype of the Marlboro man. His fascination with the subject began not long after his cousin, a Zydeco musician, introduced him to the Black Cowboy Parade in West Oakland.

We talked at the show at SF Camerawork.

How did you get interested in photography?

CL: When I was a kid, I was the person who always had a disposable camera at every event, and I was snapping away. Even in high school, in class. I still have prints and negatives from those times. But I didn't really take it seriously until 2015. I was working at a sales job, making pretty good money, but I hated it. I had always been an artistic person. I started out playing music. My cousin taught me bass when I was young. He was a superstar musician and a prodigy, and I would play in his band. I always had one foot in the corporate world and one foot in the artistic world.

In 2015, I was 31, and I decided to just quit my job and make it as an artist. With my last check there, I purchased a 35mm camera, a Pentax K1000, and a consumer-level Canon T6. I started making photos, and a friend tapped me on the shoulder. She was the vice president of a real estate company, and she liked the photos I took of her child's birthday party. She asked, “Hey, do you want a job taking real estate photos?” That's how it started: photos for work with the digital camera and street photography with the 35mm.

Did you get interested in horses as a kid? Or did that come later?

CL: I've always kind of been around it in a way. I have family members who have land. I had a great aunt who had a farm in Hayward [California]. She was originally from Louisiana, like my mother. My mom is from Louisiana, and my dad is from Houston, Texas. I have country cousins, [laughs], who we would visit. My uncle actually had a horse in a stable in North Richmond [California].

A lot of my family came during the Great Migration to the Bay Area, and the culture traveled with them. I feel like the culture of horses is not too foreign here in the Bay Area, particularly for Black folks whose ancestry is from the South. I would say I'm a first generation in California, and because my family is all from the South, it's not something that's foreign to me.

Did you grow up in the Bay Area? You were born in Hawaii, right?

CL: I was. My dad was a criminal investigator for the Navy NCIS, so we got stationed as if he were an enlisted person, but he was a government agent who worked for the Navy. I was born in Hawaii, and we moved to Berkeley [California]. My parents grew up in the Bay Area after they left the South. My mom grew up in Richmond, and my dad grew up in San Francisco.

Shortly after we returned to Berkeley, my dad got stationed near Washington, DC, so I lived in Maryland between the ages of four and seven. After that, we lived in Japan for four years. Following my parents divorce, I came back with my mom to Richmond as my mom's side of the family was there.

When did you start getting interested in photographing Black cowboys?

CL: My cousin is a Zydeco musician, which is Louisiana Creole Music that is often associated with country stuff — line dancing, that kind of thing. So, even though he grew up here, he was always back and forth between the Bay Area and Louisiana. Zydeco music draws a specific type of crowd, folks who are from Louisiana, and there are a ton here in the Bay Area. We would go with him to the dances, and people would be wearing cowboy hats and boots. When he was booked to play the Black Cowboy Parade in Oakland, we would often go to support him there for numerous years. That lifestyle was kind of romantic to me. I’ve always been kind of exposed to it. My grandfather would always watch Little House on the Prairie. My grandfather just loves westerns, so the culture surrounding cowboys was something that was probably in my subconscious for a long time.

You had exhibitions that dealt with this topic before, right?

CL: Yeah, “been here” was the installation I did at CUBESpace in Berkeley, which was curated by Leila Weefur. It was an installation featuring two video pieces. Prior to that, my thesis exhibition at CCA was also entitled “been here.” The exhibition included that video piece alongside a 15-foot vinyl cowboy, and a 3D picket fence painted with the Pan African flag colors. I called it my Black Picket Fence.

The video is part of a long-term documentary project that I started in 2017. I started documenting the Black rodeos and the Black Cowboy Parade in West Oakland. Then I traveled to Louisiana with my family in 2019 for Mardi Gras and stayed with family friends who have their own ranch. It was kismet.

My cousin has a ranch where they house other people's horses. I was there with our family friends and my cousin, Julie. She actually inspired me to make this work and told everyone, “Hey, Chuck is a photographer, and he's covering rodeos.” This family friend said, “Oh, really? Well, we have one tomorrow. Do you want to go?” Some of these images came from that experience.

How do people react to you taking their picture?

CL: Honestly, every person that you see in my work is engaging with the camera. You can tell there's some sort of exchange there. Some of these are candid photos of folks who I don't know at all, but they don't mind after the photo has been made. There's no pushback. Some of the photographs are set up, and I've contacted the people for the photoshoot. The subject of the photo in the front of the show is Paul Kevin Jaques. He's originally from Monroe, Louisiana, but he moved to Castro Valley, California. I found him on Instagram, and I had photographed him in 2021 and again in 2023, for this exhibition. Over that time, we became friends. One of the other subjects is my cousin, and another one is my cousin's husband. These folks look comfortable because they are. There's some sort of relationship there usually.

Do you think they’re proud of the work they do?

CL: Oh, for sure. Like I said, my cousin, Julie, who's featured in one of these photos, said, “We need to get this story out there.” At the time, in 2017, there were some white photographers who were covering this, but they were making this culture seem like a sensational thing. Like, “I've never seen a Black cowboy before!” [laughs] Where we're from, that life is pretty normal, and before there was a mascot for cowboys, Black folks were doing it. Before there was this white, rugged, Clint Eastwood or whomever, there were Black people doing this job. Originally, the goal was to get the story out there without it being sensationalized, and I just wanted to show the kind of everyday, mundane, peaceful lifestyle.

What’s been people’s response to the show?

CL: I'm doing this for the culture of the Black diaspora here in the United States. It was important to me that we're seen in the way that we want to be seen. Agency is a huge part of my practice. The response from my audience has been a lot of thank yous, and that’s important to me and really touched me. I think it's great, because the photos are here in the Marina, and you don't see too many Black folks up here. At the opening, I felt like a marker of success was for there to be a lot of people of color in this space who you wouldn't normally see.

Where is this going next?

CL: I’ve been in contact with some folks in Nacimiento de los Negros, which is a community in Northern Mexico that translates to Birth of the Blacks. The village includes descendants of enslaved Black folks from the U.S. in Mexico. Of the original cowboys, 75 percent were something other than white – Native American, Mexican, and Black. These folks all live there, and they celebrate Juneteenth but call it Dia de Los Negros, or Day of the Black.

For my first trip to Nacimiento de los Negros, I want to immerse myself and not shove a camera in their face. I’m there to see how they want to be portrayed and learn what’s important to them. I found a photographer, Carolina Fuentes, who had been in Nacimiento de los Negros. I explained the project to her, and she said, “I love the photos and I love the ideas.” She reached out to liaison with them, and they said I’m welcome anytime. I hope to go later this year.

There are Black cowboys in Haiti too. I have a friend from Haiti and they told me that cowboys there are viewed as being hyper-masculine and heroic. Another friend grew up on a farm in Brazil, and she said there are cowboys there too. I guess it’s not surprising or shocking that Black cowboys are everywhere — not to me anyway.

What other projects are you working on?

CL: I’m a media fellow at Kala Art Institute, and I started a new body of work of self-portraits that are introspective, vulnerable, and redefine masculinity. That work will have a video element, but for now, it’s self-portraits with me and with my dad and brother. The work deals with mental health, facing your shadow, and addressing the core traumas brought on by your first relationship.

Then the Berkeley Art Center is doing a show about the family photo album from a nonwhite perspective. They gave me a platform, and I organized an exhibition. It’s all family archives, but there will be video, photos, painting, and sculpture. Trina Robinson who has been getting some attention lately, [she is part of the show, Bay Area Now 9 at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and a finalist for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s prestigious SECA award], is in it, and a few other artists who should have a bigger platform. There’s room for everybody.

On February 23, I have a video in another exhibition at Kemper Art Museum in St. Louis, Missouri, called Space Mapping, and it’s curated by Kahlil Robert Irving

I’m also really excited about the Bay Area Farmer Training program, which is currently connected to my life but will be connected to my art someday. I think about community service and providing fresh produce to food deserts like where I grew up in Richmond.This is a nine-month agroecology program that starts in March. There are remote classes once a week, and participants visit a farm every month. It’s a life-changing thing, that I would never have thought was a possibility. I’d like to have my own homestead someday and an artist residency, so that’s the plan eventually.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!