Published August 23, 2022

Surrealist Claude Cahun's Radical Legacy

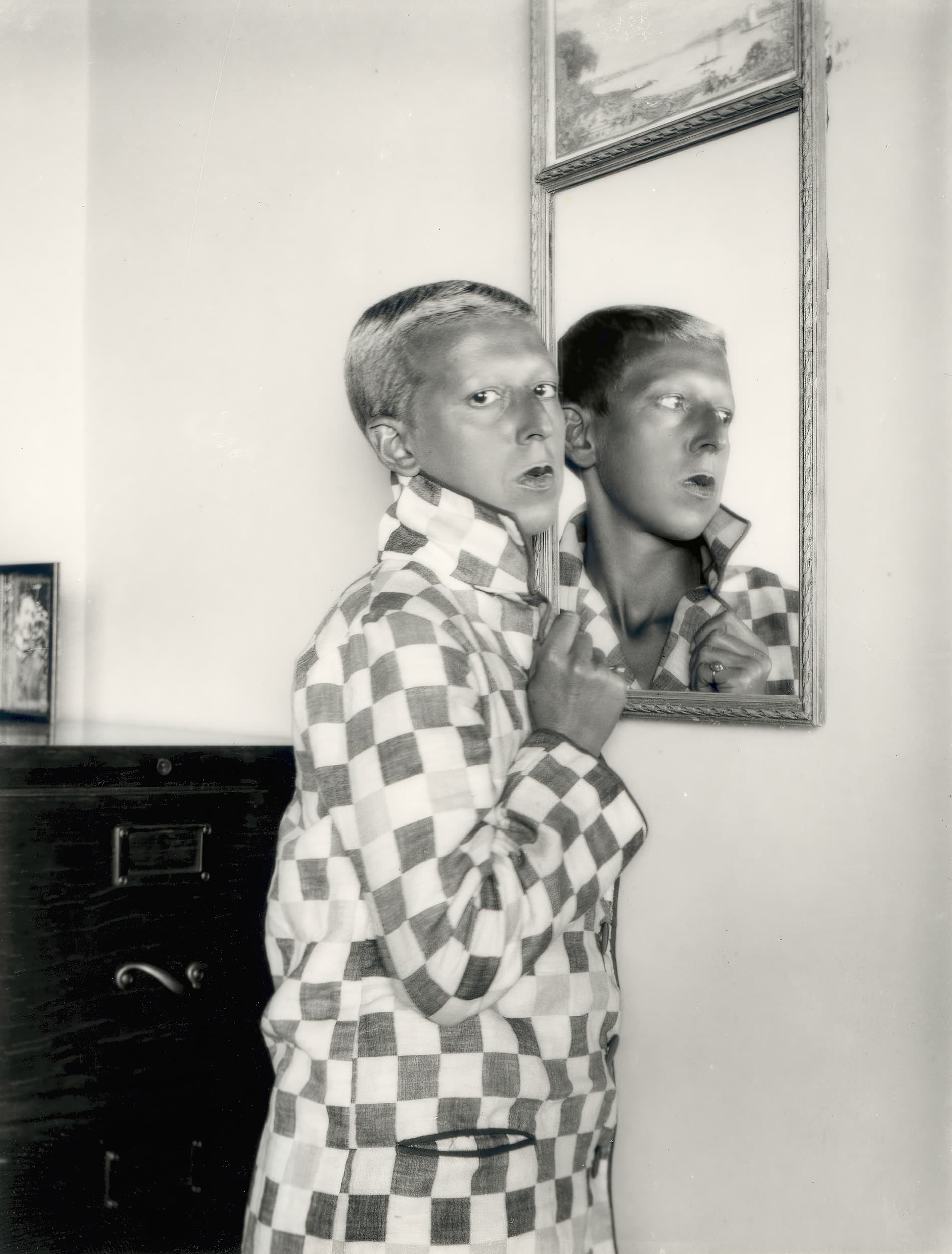

Genderqueer, Jewish, lesbian, poet, performer, Surrealist—Claude Cahun (1894-1954) balanced several different identities but refused to be confined by any. Regarded today as a significantly influential force among feminist art historians and the LGBTQ+ community, she was relatively unknown during her lifetime. While she was alive, there was never an exhibition of her photographic self-portraits, which mined Surrealism’s signature concerns of identity, desire, and individual liberation—despite her close involvement with the Parisian avant-garde.

Born as Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, she decided to adopt the androgynous pseudonym Claude Cahun as a teenager, a gesture to the multiplicity of identity that far predated contemporary discussions of transgender and queer theory and the rise of “they/them” pronoun usage.

Though entirely overlooked until fresh discourse on gender binaries emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, Cahun’s career has been subject to a swell of renewed interest. Over sixty works by the artist are currently on display in a landmark traveling retrospective at the Kunsthalle Rotterdam. Her photographs are also included in the 2022 Venice Biennale as well as in major surveys of the 20th century avant-garde, including Surrealism Beyond Borders (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Tate Modern, London) and Radical Landscapes (Tate Liverpool). Despite their execution nearly a century ago, her works advocate a revolt against conformity that feels strikingly contemporary.

Born in Nantes in 1894 , Cahun inherited an impressive sum of both financial and intellectual wealth. Her father, Maurice Schwob, was the publisher of literary journals and Le Phare de la Loire, a leading French newspaper; her uncle, Marcel Schwob, was a renowned Symbolist writer who rubbed shoulders with the likes of Oscar Wilde, Marcel Proust, Édouard Manet, and Auguste Rodin.

Despite her social and economic privilege, Cahun’s youth was marred by ostracism and hardship. Her mother’s declining mental health led to permanent institutionalization, and Cahun was largely raised by her grandmother. Bullied by her classmates for her Jewish heritage, she was later sent to school in England for two years to escape the anti-Semitism that was rampant in France at the time.

When Cahun met classmate Suzanne Malherbe (who would adopt the pseudonym Marcel Moore) upon returning to France for her final year of school in 1909, their families—both prominently positioned within the region’s cultural elite—were already well-acquainted. Notwithstanding their parents’ ardent disapproval, their fast friendship soon turned into more; it blossomed into a passionate, romantic, and artistic partnership that would last the rest of their lives.

Cahun began making her first self-portraits as a teenager, which was the beginning of a decades-long exploration of gender expression and collaboration with Moore. While it’s generally believed that Cahun directed each shot by herself, Moore was the one to press the shutter button. Using her body and shaved head as a canvas, these photographs explore a fluidity that rebelled against all norms. She represented herself sometimes as a man, other times as a woman, but—most often of all—as a bit of both.

She changed her name in 1914 in an effort to obfuscate her gender; after trying out other masculine monikers, such as Daniel Douglas, she settled on Claude Cahun due to its neutrality in French. “Masculine? Feminine?” Cahun asked herself. “It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” (i)

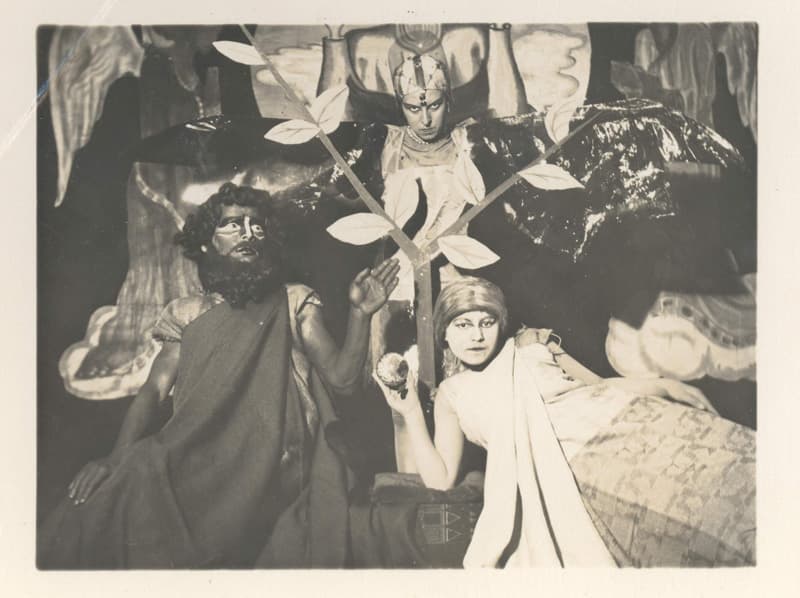

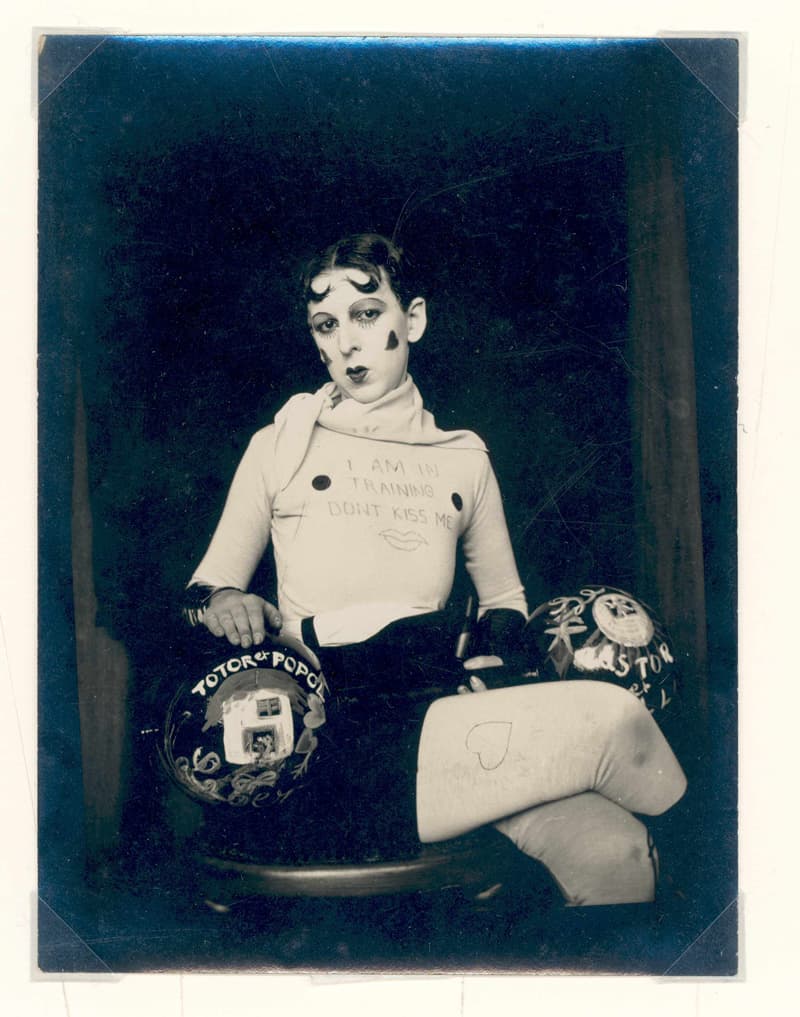

In the early 1920s, the pair relocated to Paris to immerse themselves in the city’s racy and stimulating post-World War I arts scene. As an actor with several experimental theater companies, Cahun began to incorporate elements from her stage personas into her self-portraits. Elaborate costumes and props began to crop up in her works as an amplification of gender performance; one of her most iconic images from the period, I am in training don’t kiss me (1927), depicts her as a coquettish bodybuilder toting a barbell, dolled up with cutesy heart-shaped cheeks, puckered lips, and kiss curls.

Cahun’s practice was also shaped by her close friendship with a circle of revolutionaries unleashing a wave of unadulterated expression in Paris in the ‘20s and ‘30s—the Surrealists. Her fearless approach fascinated Man Ray, Henri Michaux, and the movement’s leader, André Breton, who called her “one of the most curious spirits of our time.” (ii)

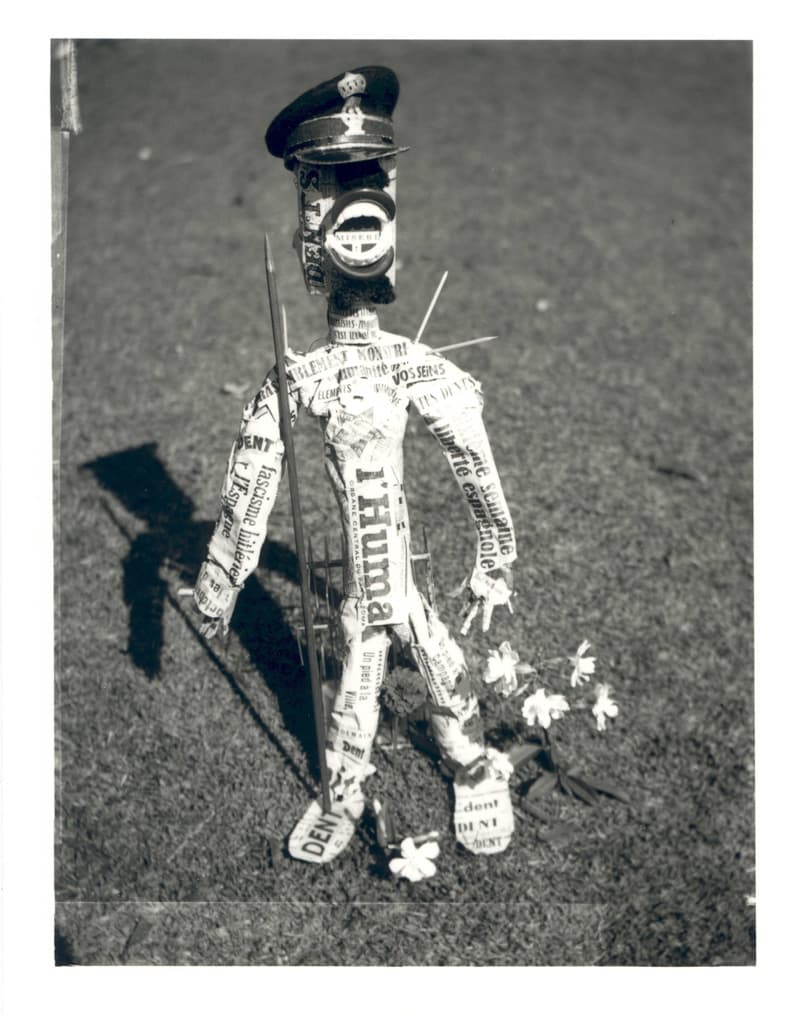

While misogyny kept Cahun from being embraced as a core member, her work embodied both the aesthetic and leftist political investments of Surrealism. Her Disavowals was a sort of equivocal “anti-memoir” that juxtaposed enigmatic photo-collages with imagined conversations, aphorisms, and Freudian dream accounts. “Until I see everything clearly,” it reads, “I want to hunt myself down, struggle with myself.” (iii) Other works from the 1930s, when she was a member of the Association des Écrivains et Artists Révolutionnaires, showcase an explicit resistance to rising anti-Semitism and nationalism in Europe. Her sculpture-photograph Poupée (1936), a small military figure composed of Communist newspaper snippets, echoed Surrealism’s leftist opposition to Stalinism.

Most of her enigmatic images were captured on the Isle of Jersey, where Cahun and Moore fled in 1937 when fascism was tightening its grip on France. The two claimed to live together as stepsisters to deflect legal punishment for their relationship. This characterization was misleading but not false considering Cahun’s mother had since died and her father had re-married Moore’s mother. As she became acquainted with her new home, Cahun executed evocative images that integrated her ever-shifting identity into the natural landscape. Her body became one with the mystical rock formations and seaweed-covered shores.

Following the Nazi invasion of Jersey in 1940, the couple stayed put to launch an incredulous two-person resistance campaign. They posted flyers around the island that impersonated an anonymous soldier inciting internal dissent. “Fighting the German occupation of Jersey was the culmination of lifelong patterns of resistance, which had always borne a political edge in the cause of freedom as they carved out their own rebellious way of living in the world together,” the historian Jeffrey H. Jackson elucidated in Paper Bullets, his chronicle of Cahun and Moore’s heroic acts of wartime sabotage. “For them, the political was always deeply personal.” (iv)

In 1944, Cahun and Moore were tried and sentenced to death for undermining Nazi forces. Their property—including most of their artworks—was confiscated while they awaited execution in prison. However, their lives were spared by Jersey’s liberation in May 1945. Upon their release, Cahun continued to make work in Jersey until her premature death in 1954, caused by health complications she developed from harsh conditions while she was incarcerated.

Keeping her photographs relatively private, Cahun was content to make her work for herself as documentation of an incredibly intimate journey with gender, individualism, and expression. It was not until decades after her death that art historian François Leperlier came across her self-portraits and introduced them to Surrealist art history. This landmark revelation challenged perceptions of French Surrealism as a largely heterosexual male endeavor and served as a touchstone for postmodern interrogations of non-binary identity and sexuality.

Calling into question the existence of an “authentic” self not rooted in social constructions, Cahun’s practice had an indelible impact on feminist and queer theory. Her portrayal of gender as a performed—rather than innate—role was a major source of inspiration for Cindy Sherman’s inscrutable images that take the malleability of her own persona as subject matter. Cahun’s images also prefigured the deeply personal portraiture of Nan Goldin and Gillian Wearing. The latter’s 2017 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London placed her photographs side-by-side with those of her French predecessor.

Reaching beyond the visual arts, Cahun’s influence has taken root in the wider cultural realm: Dior’s creative director, Grazia Chiuri, took her as her muse for an androgynous collection in 2018. Unsurprising given his predilection for adopting different personas, David Bowie found a kindred spirit in Cahun and paid homage to her with a public multimedia installation in New York in 2007.

Her wide-ranging influence is not just due to the evocative power of her images—it is the resilience and resistance to conformity behind them that resonate today. Cahun and Moore were “in the mode of investigation, who you could be, how you could be, projecting yourself into another skin, another universe,” art historian Tirza True Latimer articulated. “The photographs, the acting out, were a way of being free. It wasn’t really about producing an art object." (v)

(i) Claude Cahun, Disavowals: or Cancelled Confessions (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), p. 151.

(ii) François Leperlier, “Afterword,” Claude Cahun, Disavowals, trans. Susan de Muth (Tate: London, 2007), p. 213.

(iii) Cahun, Disavowals: or Cancelled Confessions (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), p. 1.

(iv) Jeffrey Jackson, Papre Bullets: Two Artists Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis (New York: Algonquin Books), pp. 267-268.

(v) Joseph B. Treaster, Overlooked No More: Claude Cahun, Whose Photographs Explored Gender and Sexuality, The New York Times, June 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/19/obituaries/claude-cahun-overlooked.html.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!