Published October 2, 2022

Introduction to US Community Mural Movements

Introduction

Murals are everywhere. While commonplace today, public murals—especially ones created by and for local communities—weren’t always so prominent. How these painted walls became part of the country’s visual fabric is a long and intertwined story marked by historic events and world-renowned artists, but also community activists and everyday people.

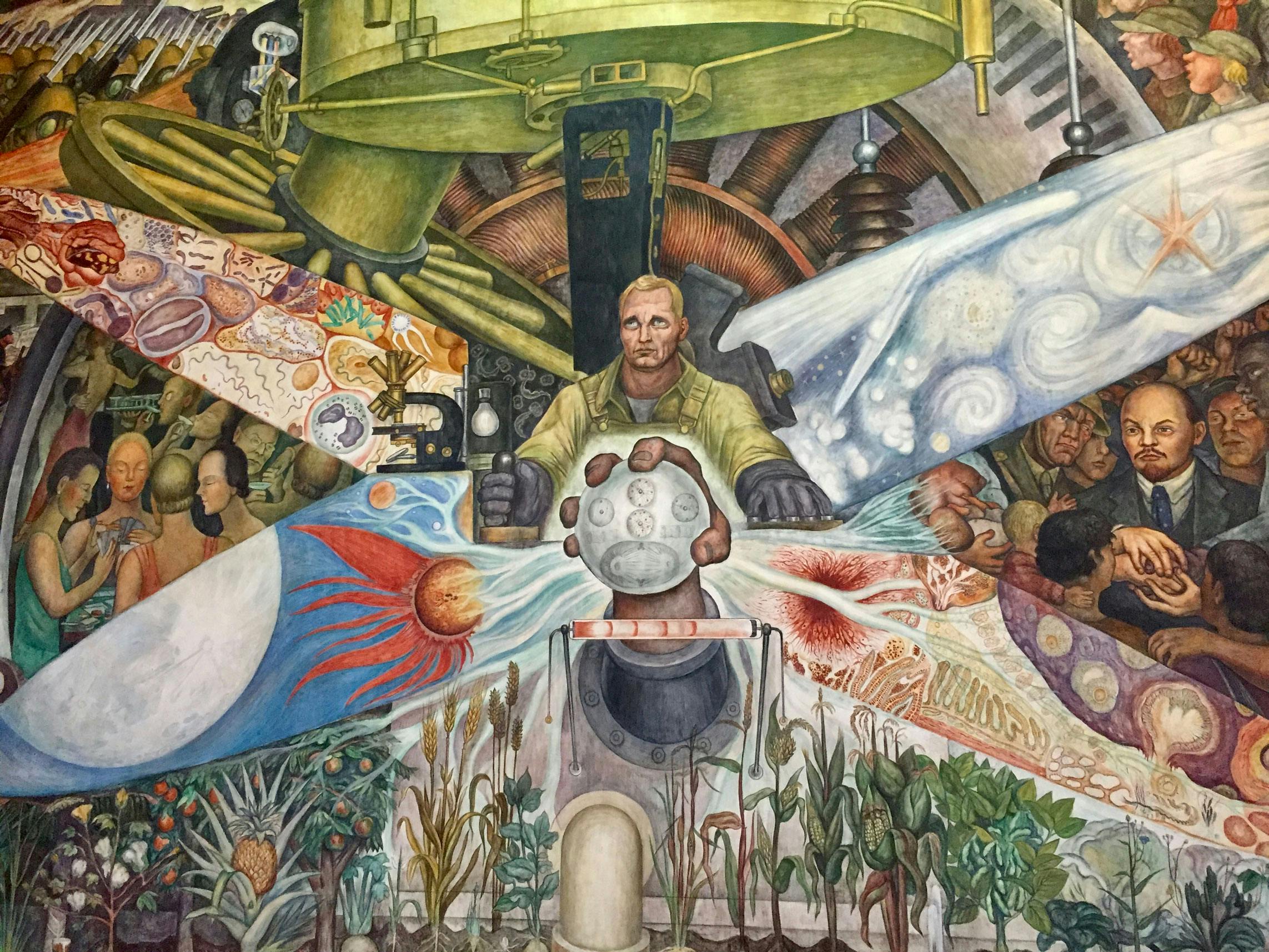

An abridged tale goes something like this: following the Mexican Revolution in 1920, artists in Mexico used mural painting as a way to promote national values, celebrate the country’s indigenous roots, and champion political interests. Their success and influence was enormous, inspiring artists worldwide to use public walls to tell stories and spark activism. This work was particularly impactful in the US, where artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros spent time painting and, importantly, teaching.

As the US crept out of the Great Depression and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was launched in 1935, artists were employed to paint public spaces and civic centers around the country. In post offices, schools, government buildings, and libraries, an official initiative of using art for public service alongside infrastructure projects was established—planting the seeds for the community mural movements to come.

So when did untrained artists—community leaders, local neighbors, and school children—start picking up the paintbrush? When did murals become a grassroots activity for civic engagement? Let’s look at three cities that gave rise to community mural movements in the US.

Chicago

In 1967, a group of African American artists, writers, and intellectuals in Chicago formed the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC). Mobilized by ongoing civil rights struggles and the emerging Black Power Movement, they decided to collectively paint a mural to celebrate African American heroes.

The Wall of Respect was born. Painted on the side of a building at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue on Chicago’s South Side, the mural featured more than fifty portraits of influential African Americans, including Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali, Aretha Franklin, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Miles Davis. Fourteen artists and photographers, including William Walker and Sylvia Abernathy, designed and painted the sections over the 20 by 60 foot wall, incorporating community input into the designs.

It also stirred another movement. Artists began painting public murals across Chicago, inspiring artists in other cities to launch similar projects integrating art with community engagement. Though the Wall of Respect was destroyed in 1971 after the building caught fire, its legacy lives on in the continued prevalence of mural projects in Chicago.

Los Angeles

If the Civil Rights Movement inspired community murals in Chicago, the Chicano Movement inspired them in the southwest and along the west coast. In the 1960s, murals became an important way for Chicana/o artists and activists to communicate values, affirm cultural identities, and advocate for change.

In Los Angeles, the legacy of Mexican Muralism had particular impact. David Alfaro Siqueiros was there in the 1930s, painting América Tropical in Downtown’s Olvera Street. Though the mural was whitewashed shortly after its creation, over time the powerful composition began to emerge from beneath the layers of white paint.

Artist Judy Baca cites this remerging as igniting LA’s community mural movement. In 1970, she began working for the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, while teaching art to at-risk youth in LA’s predominantly Mexican Eastside neighborhoods. Graffiti was already widespread—a visual method to mark space and express identity.

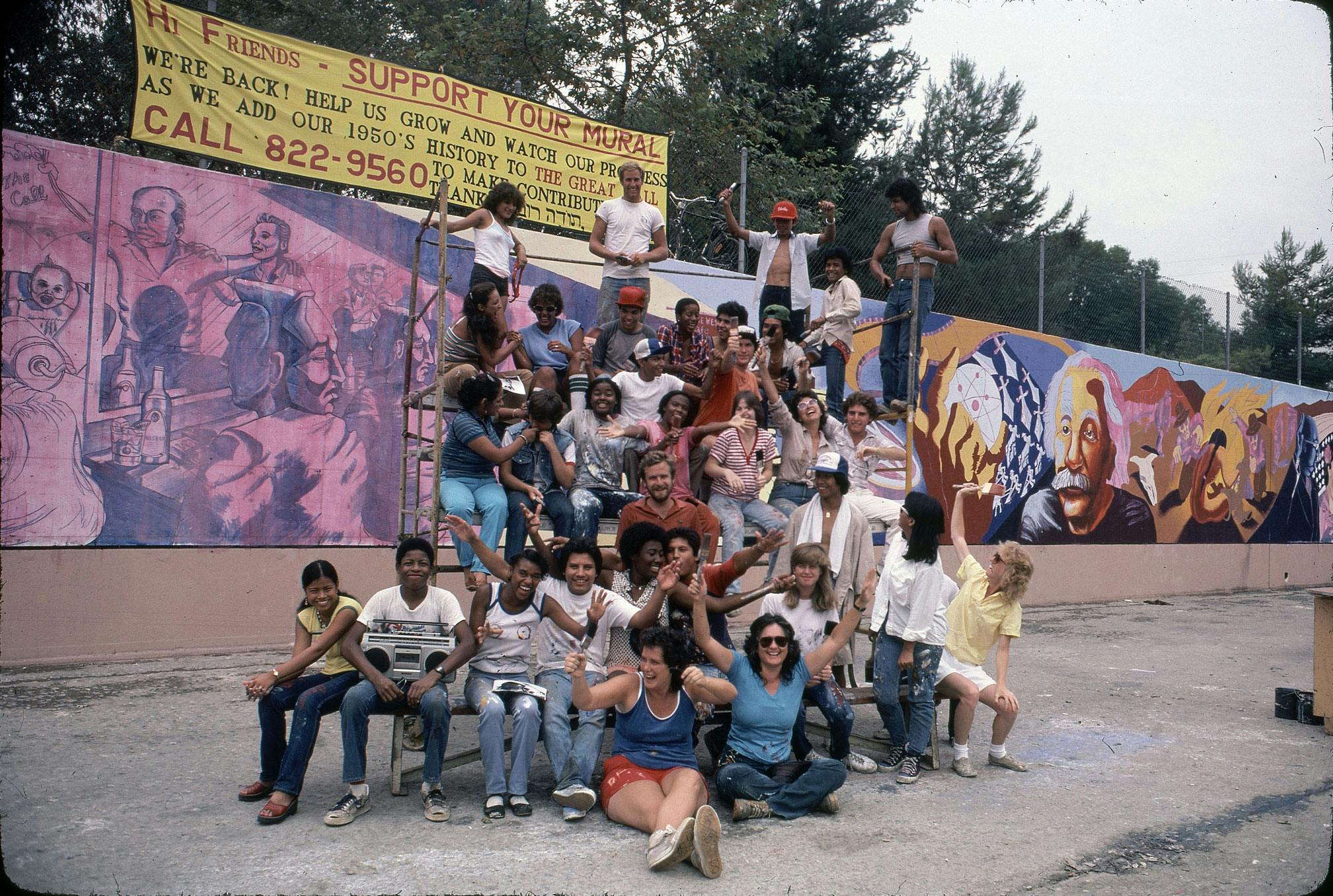

With the city’s support, Baca launched LA’s first city-wide mural program, employing young artists in her mural crews. Together, artists and youth built scaffolding and painted, working with local residents to choose subjects and themes that reflected the neighborhood’s values.

After painting more than 400 community murals, Baca and others formed the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) in 1976—a non-profit dedicated to mural production, preservation, and art education that continues to this day. Their first project? The Great Wall of Los Angeles, a cultural landmark and arguably the most significant narrative mural created in the second half of the 20th century.

San Francisco

Up the coast in San Francisco, a similar story was taking place in the Mission District, where Latina/o/x artists and activists were using public walls to reclaim space, celebrate their heritage, and promote social change.

Balmy Alley, a one block long alleyway in the Mission, became a centralized space for creative expression. The earliest murals date to 1972 and were painted by artists working with local school children. It was also where Las Mujeres Muralistas took off.

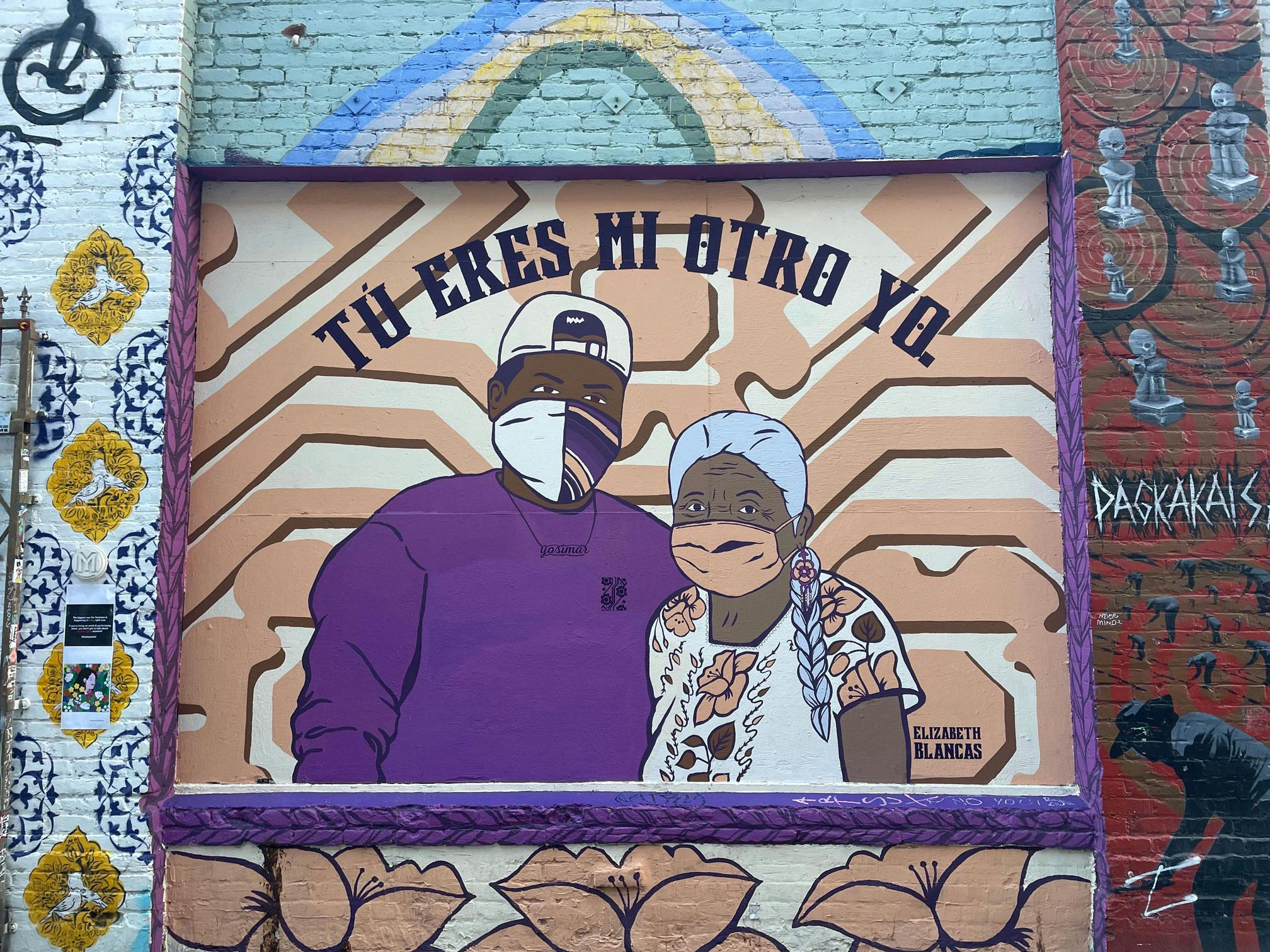

Founded in 1973 by artists Patricia Rodriguez and Graciela Carillo, the artist collective created murals that celebrated the beauty of Chicana/Latina-American womanhood and the diversity of Latina/o/x cultures within the Bay Area. They and other artists transformed Balmy Alley and the Mission District into a hub for community murals, walls continuously updated with fresh coats to reflect what was happening in their community and in the world.

In the 1980s, for instance, a group of artists painted murals in Balmy Alley celebrating Central American cultures and protesting US intervention in conflicts in El Salvador and Nicaragua. Today, visitors to Balmy Alley can encounter these historic murals and discover new ones, while also visiting Precita Eyes, an important center for mural arts education.

Legacy

By the 1980s, community murals were a common tool for public engagement in cities up and down the United States. Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco remain significant centers for community mural projects, while other cities have launched exceptional mural movements of their own—notably Philadelphia, which claims the title of “Mural Capital of the World.”

Philadelphia’s community mural movement grew out of anti-graffiti campaigns, as artists worked with local youth to translate their impulse for public expression into murals. Today, the city is home to organizations like Mural Arts and Monument Lab that are leading conversations around the past, present, and future of public art.

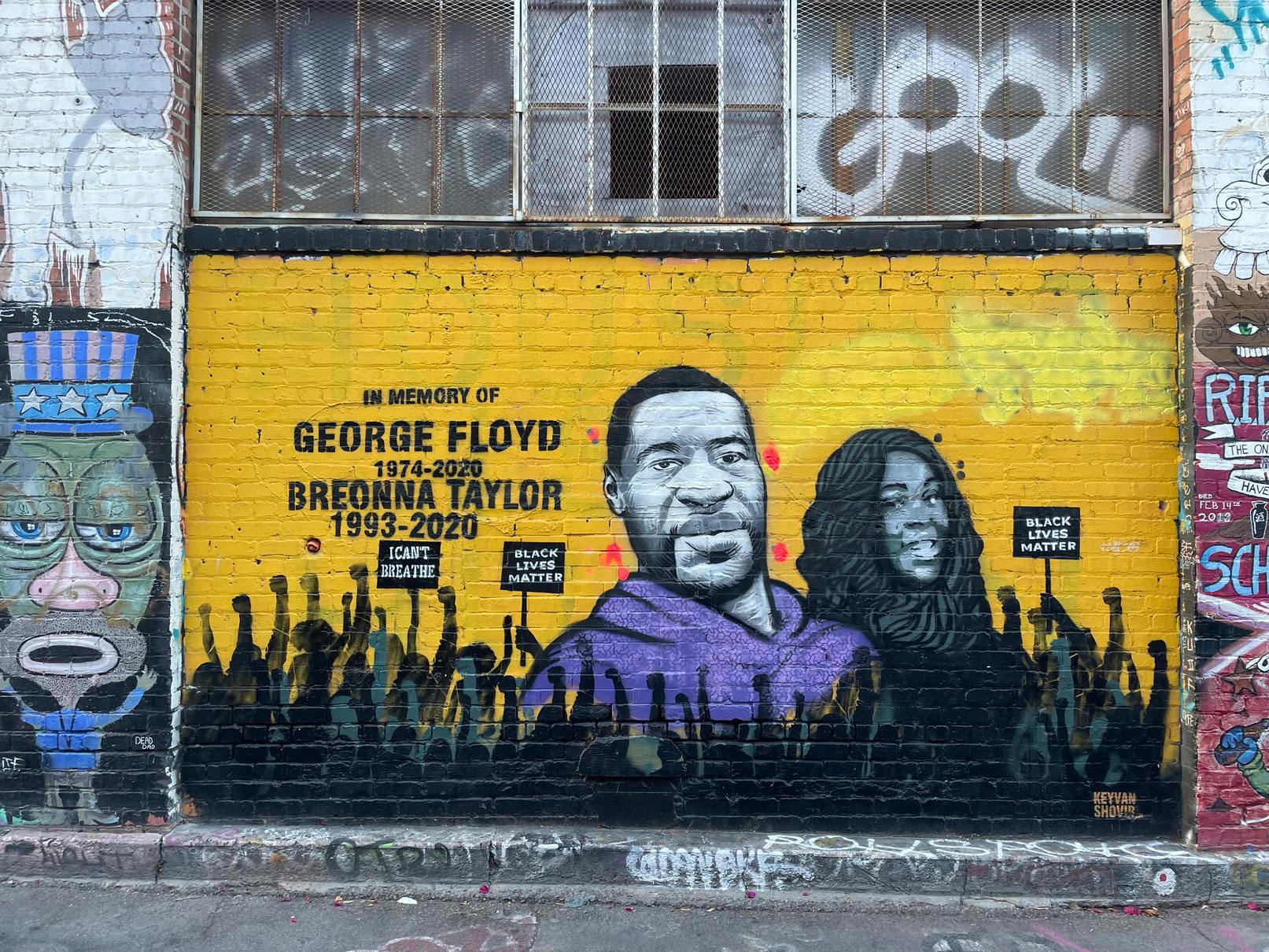

As a country, the US has grown to expect murals. In times of political upheaval, we anticipate the quick creation of painted memorials or calls for social change. This momentousness is evidenced in the powerful murals painted in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd. Sides of buildings became public memorials to lives lost, as entire city blocks were transcribed with “Black Lives Matter.” Public art, once again, became an important tool for civic discourse.

Along with activism, mural painting remains a common pursuit for beautification initiatives and youth engagement. Its collaborative nature facilitates opportunities to bring neighbors together or spark creativity in students. Many of these murals endure for generations, becoming part of the visual identity of a community. Others only last a few months, walls repurposed for new coats of paint. While the nature, style, and value of community mural projects is always evolving, what remains is a constant desire for public visual expression that boldly reflects the communities these walls exist within.

Online Resources:

City of Chicago Mural Registry

Precita Eyes

SPARC

Mural Arts, Philadelphia

Recommended Books:

Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement

The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago

Street Art San Francisco: Mission Muralismo

Judith F. Baca

Philadelphia Mural Arts @ 30

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!