Published January 13, 2023

Pixels, QR Codes, and Square Paintings: In Conversation with Artist Julia Rooney

Artist Julia Rooney’s multidisciplinary practice encompasses painting, works on paper and installation that explore the tensions between analog and digital media. Her paintings offer both two and three dimensional approaches to abstract image making focusing on the square shape as a foundation. Through digital media in the use of QR codes, pixels, and grids are embedded with rigid right angle squares, Rooney challenges these images with her hand by cutting, sewing, drawing/painting loosely, with thick and thin marks bringing us closer to the analog, to painting, and to what is human.

After making new work at the Joan Mitchell Center art residency in New Orleans this Fall 2022, Rooney will have a solo show, Album, at Freight+Volume in Tribeca opening January 20, 2023 focused on painting.

We met in her studio in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, inside the historic Brooklyn Army Terminal where the visionaries behind ArtBuilt have fought for low rent studio spaces. Our conversation centered around the process and ideas behind her new work intended for the upcoming exhibition.

I see that this exhibition will have a QR code painting hanging at the gallery’s entrance window display, which parallels a similar painting in your last show “@SomeHighTide” (2021) with Arts+Leisure. What I’ve found curious is that you've taken the shape of the QR code as a base structure for some of the paintings in your upcoming show with Freight+Volume. One of them is functional where we can be connected to a video online and others are completely invented but that base structure is recognizable and resonates in our 21st century minds. What drew you to the QR code as a base structure for painting?

JR: As artists, writers, and curators, we are constantly reading each other’s work. During the pandemic, as QR codes became such commonplace means of communication, I began thinking about the idea of a painting literally being read by a machine as opposed to the ways we metaphorically talk about a painting being read. The idea that a device could have a relationship to a painting is fascinating to me. The QR code painting was the first time I thought about painting being in service to a different kind of audience member.

To a person, it’s just an abstraction of dark and light—and when I’m making the painting, it’s not readable. Then there is a moment when the last square gets added, and suddenly the phone registers it. This painting is now linking us to a space that we’re not in, which is also what painting has always aspired to do: to transport you to another place, metaphorically speaking. The QR code painting takes this notion and plays it on itself. There is also a built-in clock to the painting—an inherent “doneness” the moment it becomes readable.

Often, with abstract work, this is the fundamental question: When is a painting done? Why do you keep working on it? Some of these paintings I’ve been working on for years, so it’s clearly a question deep within me.

Even though the QR code appears to us as an abstract image composed of squares of all varying sizes and colors, it is in a finished state and also communicates with a computer. Who are some artists you think about when making your work, and who do you think in the art historical lexicon would be interested in the QR code?

JR: There is so much about Duchamp’s practice—and specifically his relationship to painting—that I respect. Even as he embraced the conceptual, his work never got away from the importance of objecthood, the thingness of the thing. There is often a desire or pressure for artists to develop a recognizable way of working—stylistically—and what fascinates me about Duchamp is he was driven not by the way something looked, but rather by the way he thought about it. He resisted “style” even though he never fully divorced himself from the material world. I connect with this idea of exploring how something is read: viewing a shovel or a urinal differently. If we read it this way it becomes this thing, if we read it that way, it becomes that thing.

Human eyes read my QR code painting as an abstract pattern; it’s only the smartphone’s “eye” that determines whether it works or not. For instance, if one square changes, or the lighting is too dim, or the link that it goes to is broken, it won’t work. These may be imperceptible changes to our eyes, but to the machine, these changes matter. They change why and how it’s read.

Paint has this ability to accrue time and can layer previous versions of itself, even though in the end, we only get to witness the last flat layer. Painting is still this compression of multiple moments of making.

Your multimedia work wavers between the analog in the medium of oil painting as well as works on paper, text, and the digital, engaging people in interactive installations. The work you have chosen for your show are oil paintings you did in New Orleans. Could you tell me why you chose this particular medium for this body of work?

JR: I went to this residency knowing only that I wanted these to be square paintings of varying sizes. The square is a form that doesn’t have an inherent up/down, landscape/portrait orientation and it is a shape that can be flipped on itself and still look the same. I wanted each painting to feel like a zooming in or zooming out of a square, where the smallest unit would be very small (2-in by 2-in) and the largest unit would be very large (6-ft by 6-ft).

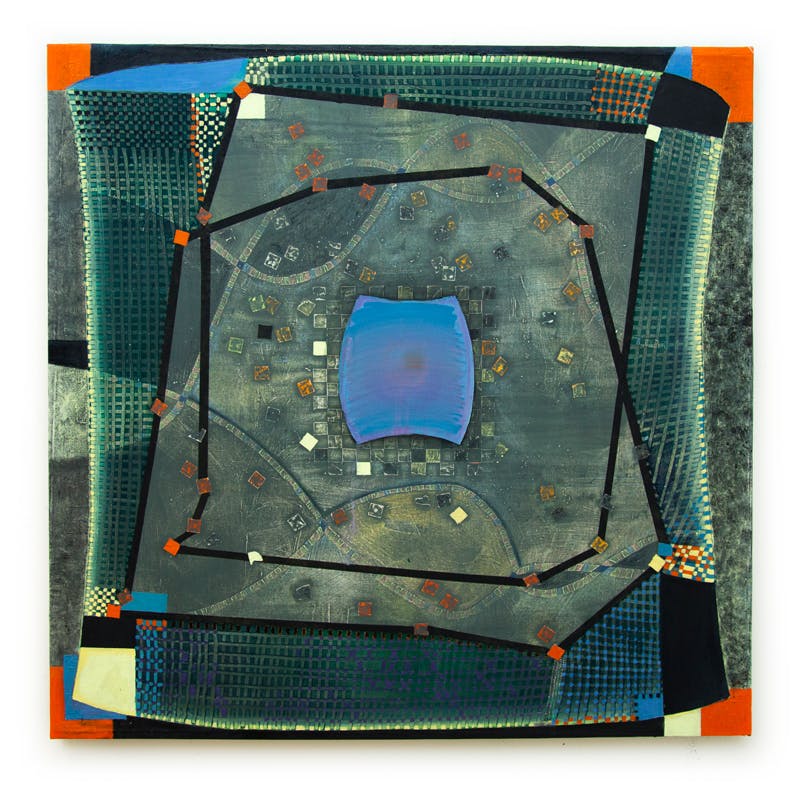

Thinking about differences between the digital and the analog world is something you address in your work. It’s interesting that the pixel is in essence a square, and your work is all on this framework of the square. The square as an abstract form also appears in multiple ways: sometimes it’s very soft, there are more painterly drips or it’s highlighted, and this one “OBJ 1115” (2022) especially reminds me of your work “Greenscreen” (2022), which was a more interactive piece. Here we have this centered chess board made up of squares and squares are scattered all over the surface as if they were leaves blowing in the wind. What is it about the squares or the pixels that draws you to this subject matter?

JR: I love that description of leaves blowing in the wind because that is similar to how this piece came about. All these squares are cut outs (made from dried molding paste), and as I dropped them, they scattered around randomly. There is an element of chance in how they became arranged. Allowing for chaos and randomness contrasts with the rigidity of a square system.

Like a chessboard, part of the work is very gridded and then it dissolves into a more organic logic. I’m using the square as a framework for taking apart its own logic—using an inorganic form to gesture towards an organic movement. And likewise, how does an organic form conform to or deviate from the grid?

By an organic form you mean these more curved lines?

JR: Yes, I’m referring to those DNA-like strands that come in and out of each other and form these void shapes in the middle.

Resembling a double helix?

JR: Yes, and the idea that there is a structure underlying what we ultimately see. I’m interested in painting not just being an optical thing, but rather a structural one. How did this thing come about and why does it look the way it looks?

Like our DNA does to us?

JR: Yeah. How many combinations could’ve been possible? We’re just one instance of millions of chances.

Is there anything you brought with you to New Orleans to get started with this body of work?

JR: I brought stretcher bars, unstretched linen, and paint materials. I also brought a few canvases that were in moments of crisis and served as a skeleton for new work. I wanted to leap off these canvases that had previous lives within them. Paint has this ability to accrue time and can layer previous versions of itself, even though in the end, we only get to witness the last flat layer. Painting is still this compression of multiple moments of making.

What was it like to revisit these old works and then repurpose them into a new life?

JR: The process often involved building up the old work to a fairly complex, detailed state. After this immense buildup, I would literally have to cut out sections with a blade, which is very different from painting over. While I do a lot of scraping down, washing out, and sanding down, there is something very specific about excising a part of a canvas from the image. It’s kind of like a cut in cinema, where there is an actual gluing of one frame to another. In this process, there is a fair amount of letting go of original intention for the painting. Almost like forgetting what you once wanted it to be and looking at it for what it is now.

There are some instances where you took on that role of a seamstress. In “OBJ 0923” (2022) it seems that most of the canvas has been cut up and restitched and supported on a different substrate. What did it feel like to do that with your work?

JR: I think it allows me to start again. Working the paintings for such a long time, there is a lot of labor in them–but sometimes cutting out a section is a way of acknowledging it doesn’t matter how many hours you put into it. Sometimes it’s a split-second decision to cut it all out because that is what the painting is asking for. I let go of the preciousness and the control. There is also something particular to canvas or linen which allows for that: they are super durable materials but are also very soft. You can cut them with scissors or sew them by hand, unlike wood.

I’m curious about this shape which does reappear a few times “OBJ 1115” (2022), which has four enclosed curved edges, but seems like there would be straight edges, but all the angles are obtuse. Where does that shape come from? It’s very unusual.

JR: It came from working on stretcher bars during the pandemic that were too weak to maintain the integrity of their structure. The rigid bars became bowed or warped under the pressure of canvas being stretched over them. I became very interested in that imperfection as an impetus for how the painting is developed. The ever-so-slightly not-a-straight-line and not a right-angled painting frame is how the warp imagery evolved. It’s tilted or off balance.

In OBJ 1007 (2022), I was also exploring the potential of unstretching/stretching as a way of working within and against the square. When I re-stretched the canvas, I tilted it on the stretcher bars, so that the original painted surface was off-kilter. I was playing with the idea of working within the rigidity of the grid, but recognizing that we’re not right-angled animals, we’re soft bodies that contend with the grids of our constructed world and the digital world.

Going back to the thingness or the objectness, another facet your work has played with the notion of scale, with miniature paintings (2 x 2 inches), and much larger ones (6 x 6 feet). The smaller ones correlate with the experience of a digital image on the screen, on a phone, and in some of your past shows you have asked us to confront the physical space and how our bodies experience the work when we’re faced with it in a physical and architectural context. In the show there are a few examples of tiny paintings themselves, but I noticed some of the paintings, much like the cutting, have become relief-like with 2x2 inch formats being added onto the painting so it has more of that objectness. Could you talk a little more about what went through that decision making for you?

JR: Many of these paintings have felt like a process of assemblage, of building out an image in a really physical way. From far away the image may read as a flat grid—a painted illusion— but when you get up close you notice it is assembled out of textural parts: actual 2-inch canvases built into and on top of the surface, as though to say: pixels are real. Pixels are material. The digital world is material. And importantly, the digital world has been designed by people. Even though digital space so often flattens our three-dimensional world, it is its own dimension, its own space—and that space is not inherent, it is an architecture constructed by programmers and by companies. Social media does not have to look the way it does. We could have healthier algorithms, we could have ethical search engines. These are not default conditions.

As a painter, I have the capacity to construct a space that can be both flat and textural, illusionistic and real. Sometimes my grids are built from swabs of paint and other times they’re cut up squares of canvas. I employ all these strategies as an enduring reminder that the grid is always made, always built, always physical.

I also see that a lot of these are a world within a world within a world, it’s a constant deepening or distancing from one world to the next, whether it’s the material or the paint itself. Sometimes it feels like a wormhole and going into a different universe all together, so I really sense this feeling of a digital rabbit hole when looking at some of these pieces.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!