Published October 12, 2022

Paul Anagnostopoulos on Painting as Grief, Joy, and Everything in Between

Paul Anagnostopoulos (b. 1991 Merrick, NY) is an artist working in acrylic and oil painting. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from New York University in 2013 with his BFA. He interned at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy during the 2013 Biennale. Paul has completed 10 acclaimed artist residencies in the states and abroad, most notably the Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, VT), the Wassaic Project (Wassaic, NY), and the Association of Icelandic Visual Artists (Reykjavík, Iceland). He presented solo exhibitions at Dinner Gallery (New York, NY), Leslie-Lohman Project Space (New York, NY), and GoggleWorks Center for the Arts (Reading, Pennsylvania). Paul’s work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art Archives and Library, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, and Yale University. His work has been featured in New American Paintings, Artnet News, VICE, and Friend of the Artist. Paul is currently pursuing his MFA at Hunter College in New York, NY.

Anagnostopoulos, who is also featured on Testudo, currently has a solo exhibition, When Heroes Fall, on view at Dinner Gallery from September 8 through October 29, 2022.

I'd love to start our conversation by considering how your work has shifted over the past few years. We first met in 2019 through NYC Crit Club, and many of the bodies that you depicted were very detailed, chiseled, and toned. While we still see some of that here, When Heroes Fall offers softer bodies, translucent bodies, or parts of bodies. Why do you think they've changed?

PA: I started this recent body of work with an intense exploration of mythological desire, melancholy, and tragedy, but it really started in 2016 when I put my own interests together and started building a visual language and queer lens for it. Back then, I was predominantly a print maker and drawer, which is likely why my work is still contoured, bold, and graphic. Now painting allows me to work without a print studio and in my own space.

I was trying to paint like I was making prints. It was about flatness, patterning, and building a linear image. But as I kept working in paint, I wanted to introduce well-rendered, three-dimensional aspects to build space between dimensions. We get this push and pull, even vibrational, space that's both deep and flat at the same time. I think it comes from both my interest in Surrealism and playing video games growing up, because in video games, gradients are a flat digital space, or screens we can't enter. But then at the same time, a gradient suggests an infinite space we could hypothetically enter.

I still reference drawings I’ve made of sculptures, statues, and objects, but I've also been drawing people too. There’s a lot of direct portraiture here—of my body, my partner's body, and friends. It's become an investigation of the human form, the figure, and the flesh as opposed to just studying sculpture.

I noticed that. Take the flames in Golden Hour Faded Black, for example. Fire is rendered not only as detailed lava spewing from a volcano, but also a flat, graphic, almost Hot Wheels in the 80s aesthetic.

PA: Yeah. That’s why the move toward painterly representation just came natural. I’ve already explored 2D a lot, so I’ll try 3D, go back to 2D, then mix them together. So for this show, I really wanted to explore painting and have the oil paint be oil paint and not just a flat surface, so it can render flesh and touch and tactility.

It also shows up in the palette, too. In the first half of the show, they depict evening and nighttime scenes as opposed to the second half of the show and previous works of yours. What drew you to specifically changing the saturation and palette?

PA: I’ve made works that use darker tones before, but this show has way more variety. When you walk to the right of Dinner Gallery, there's a smaller room, and to the left is a larger room. I wanted to use this layout as an opportunity to consider two opposing forces coming together to create a paradoxical, dynamic tension. That’s why the works here are about both pleasure and pain, abundance and loss, and other opposing forces. There’s a bittersweetness to it conceptually, which even manifests palette change you're mentioning. Even a single painting’s complementary colors do this visually.

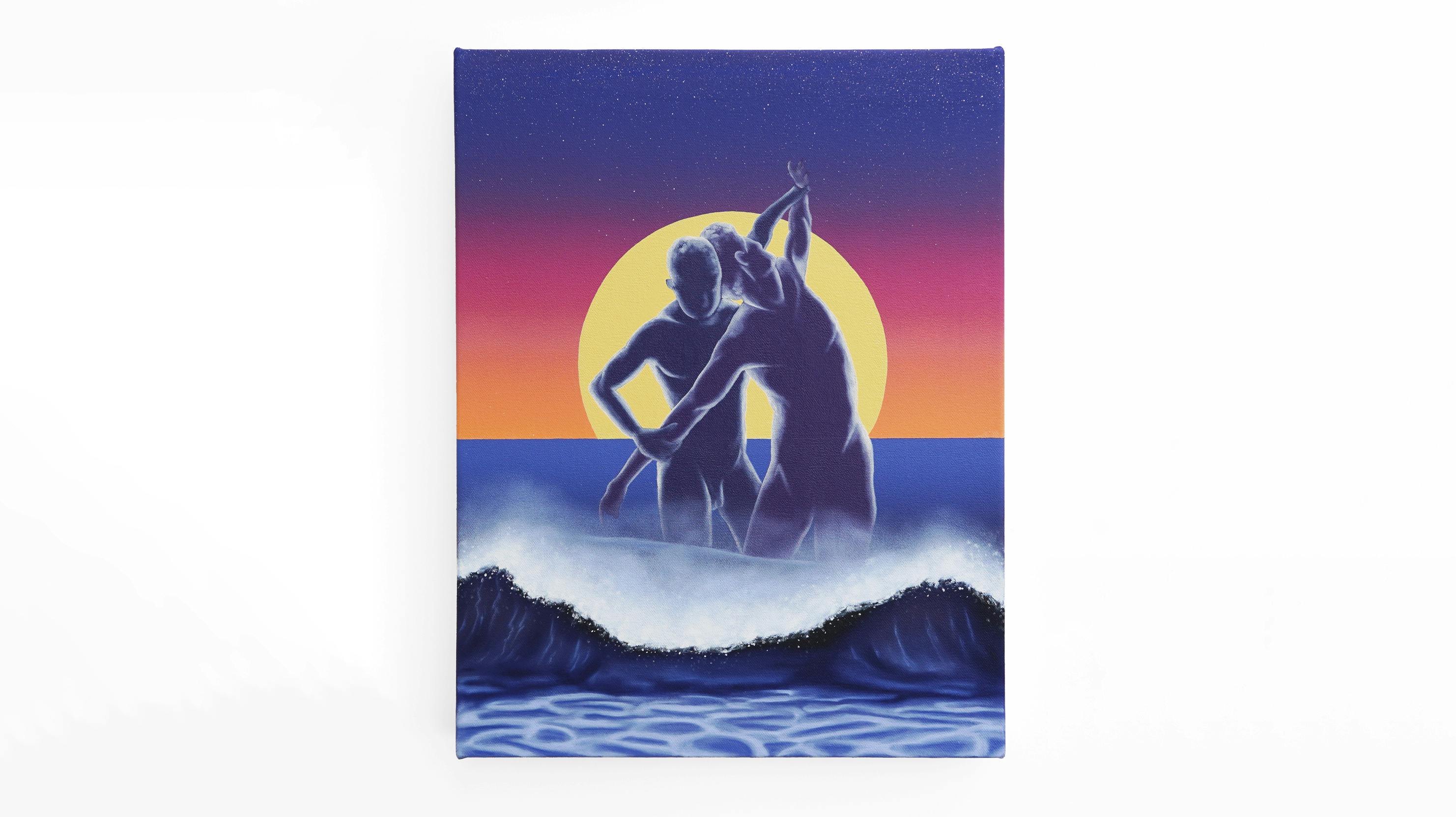

As you enter the gallery, you first see The Arms of The Ocean Deliver Me, which is one painting of two figures in front of the setting sun. There are vibrant, bright sunset tones toward the bottom against a dark starry sky creeping down from the top. It’s the entry point that transitions between both rooms. In the room on the right, which was the more somber nighttime scenes, the paintings are a bit quieter and consider loss, grieving, reflection, and the peace that comes with nighttime.

The room on the left is a foil to the room on the right, which has Golden Hour Faded Black’s erupting lava, really bright twilights, purple lightning, and an arc of passionate storytelling.

Even if these two rooms are separate in tone and intention, you still have consistent motifs across the works too, including flowers, mountain landscapes, water, and hands holding or almost holding. What draws you to return to these symbols across paintings?

PA: Symbols have cultural meanings and interpretations that change over time and across cultures. Flowers have been a symbol for life, death, and the cycle of growth itself across mythology and across societies. People themselves attach their own meanings to flowers. A lot of flowers are actually stand-ins for people in my life or relationships I've had, for example.

My two grandmothers on either side of my family—one was Greek, the other Italian—had gardens. They really taught me about culture, history, language, and mythology. My Italian grandmother had a miniature Pieta above her sink and my Greek grandmother had all these kitschy vases in her home. I learned about art and art history through kitsch and souvenirs. These objects, especially cheap copies of well-known originals, are symbols of adoration, because it's something that's so important it is mass produced for everyone to have.

With mountain landscapes, I've always found myself in mountainous environments at residencies or important times in my life. It’s a specific type of terrain where I feel a connection to the other world or some sort of higher power. I have had these really emotional experiences at these grand landscapes.

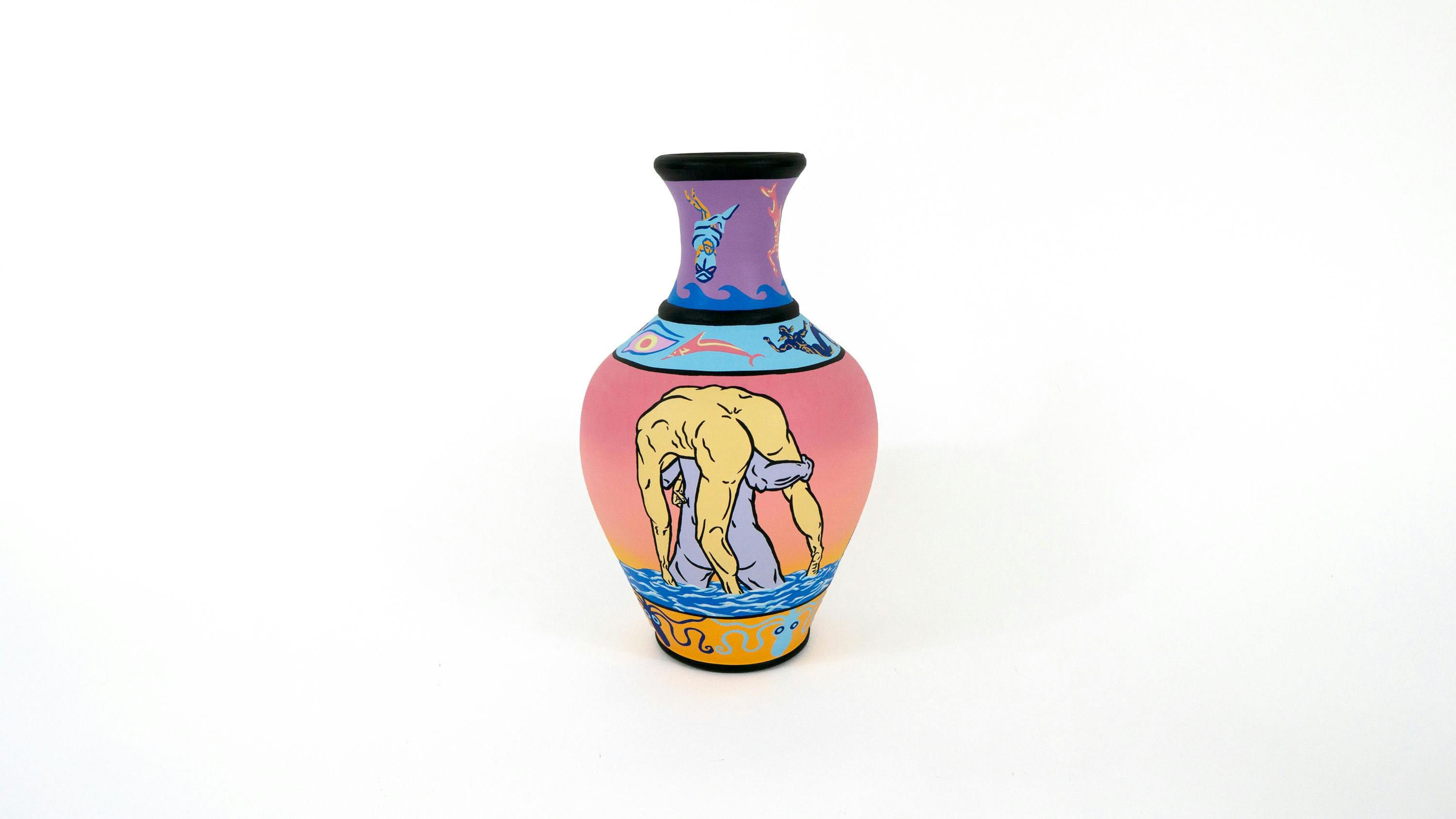

How did the two vases in the show come into your care?

PA: These pieces were a surprise for the show. I’m a collector in terms of getting anything I may gravitate toward. It may be some seemingly random object, but I'm usually like, “I'll use that one day. I don't really know what for yet.”

I was in Greece in 2019 for a residency. There was this potter in Delphi who had these unpainted pots around the studio. I bought them, thinking I'll use them for something one day, and who knows what they’ll be.

I've always used pottery in my drawings and paintings. I thought, “What if I just paint on this instead of a canvas? How will the image change?” So I gessoed each vessel with ten layers then painted three layers of each color, because it sucked up the paint really fast even though it was already glazed. I really had to race against the clock. It started as an experiment, but became a nice experience because I was cradling each vase for 30, maybe 40 hours as I painted it. It was a very tactile and sensitive type of painting.

See You In The Undertow contains images of dolphins and men carrying other men. Is this referencing a specific myth or story?

PA: I was thinking about art’s early, utilitarian function as a visual marker that references an object’s purpose or intention, like drinking water and wine, which are two of the most important liquids throughout human civilization. And so for that vessel, I was considering water and the myth of Dionysus and the Tyrrhenian pirates.

Water can be a weak dribbling force or a cataclysmic force of nature that can totally destroy everything. Water cycles reflect this idea of a life cycle and the cycle of a relationship. I was going through a bit of heartbreak, and making this work was a cathartic expression. In the myth, Dionysus, who was disguised as an old man, was captured by Tyrrhenian pirates. They originally offered him safe passage on their boat but instead planned to sell him into slavery. Dionysus then revealed his true power as a god, so as the pirates tried to flee the ship and jump into the sea, he turned them into dolphins.

It's this story of deceit and trickery, and this ultimate punishment for messing with the universe.

I see a throughline in the show—and correct me if I'm wrong—that considers making art after tragedy, and asking what queer melancholy looks like. Does tragedy guide what you work on?

PA: It’s definitely a major part of the process. Ancient histories, cultures, and mythologies are usually my starting point. I pull from celebratory stories and tragic stories that share high emotion, high drama, and hyperbolic situations.

Tragedies, in particular, are always intense moments of loss and destruction. But they're usually characterized by a rebirth. It continues a cycle of destruction and creation. Tragedy becomes a way to show this.

It reminds me of that ad campaign back in the 2000s “It Gets Better.” These days I tend to think it doesn't get better—it just gets more complicated. We can't think of emotions or histories as linear expressions, but rather cyclical moments in time.

PA: Everything repeats. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

As a queer man, growing up in the late 90s and 2000s was a very different political landscape than today. I think a lot about the losses resulting from HIV / AIDS. A lot of older gay people just don’t exist today. We nearly lost an entire generation. So many of their stories have been erased. The same thing happened with classical culture and art history. All of the queerness and celebration of the human body that was around for these ancient stories have been totally sterilized and whitewashed in contemporary America. I remember that the only mainstream media representation of gay people were straight actors playing them in movies about HIV or brief instances in which gay characters were the punchline for a joke.

I reference ACT UP, gay erotica, and pornography from that time not only to build a modern gay identity marked by tragedy, but to also reinsert those histories back into the conversation and acknowledge their erasure.

Painting and drawing is when I put myself in my own little world and process everything happening. It’s healing for me to understand, because I can then shelve something away, purge it, grow from it, and move on.

So do you think it's fair to consider some of these paintings grief work?

PA: That's definitely a part of it. Grief for me is the death or absence of love, and these works are part of a cathartic process. A lot of my own personal events will inform the decisions I make in terms of the mythological inspiration, the composition, the color, or the atmosphere. So yes, one aspect of dealing with grief makes its way into the work, but that’s just a slice of the work. I didn’t want to be one-note in terms of the show’s emotive narrative. There are humorous scenes and also celebratory scenes.

Ancient Greeks had fun stories, too. Not everything was super serious. They made dirty jokes back then. In an ancient Roman villa, you could find cups in the shape of a dog's head, because the owner liked dogs. Nowadays you see this same idea when a cartoon fan will have a Scooby-Doo mug in the shape of the character’s head. People will always be the same. We have struggles, battles, loss, and yes, grief. So it's just all different aspects of one’s experience.

So it’s more than just grief work—it’s an emotional gamut you're expressing.

PA: Yes, for sure.

Why is making art a therapeutic process to understand emotion?

PA: For me, processing has to do with focused time and energy. I’m working 20 hours, 40 hours, sometimes 100 hours on each painting. So much of my life this summer was just working. Painting and drawing is when I put myself in my own little world and process everything happening. It’s not to shut off from the world, but to pause and meditate on it. It’s healing for me to understand, because I can then shelve something away, purge it, grow from it, and move on.

I'd love to talk about Contemplating God, which is one of my favorites in the show. What were you thinking about when you made that piece?

PA: I wanted to capture the specific moment or feeling when you wake up at four or five o'clock after falling asleep on the beach. It’s that amber golden light when your eyes are still fuzzy. You're looking around, and the light is sharp in certain places. There could be a figure in the distance, so you just sort of see a silhouette. It’s such a good feeling. You’re relaxed, and everything feels warm and peaceful.

I was also thinking about moments in myths when the speaker of the story runs across a God in the forest, and they catch this glimpse of the divine. It’s a shocking but calming experience when you come upon a surprise like that and it’s so prevalent in mythological stories.

There’s a similar body in Forever Haunted By Our Times. It brings us back to the concept of a body both there and not there at the same time.

PA: It’s a way to play with and offer a new dimension to a silhouette—a little more mysterious and less obvious. It brings moments of humor into a painting like Forever Haunted By Our Time, which has more serious undertones. That piece was based off of the shield as a symbol of protection, but that being said, Medusa saw her own reflection in a shield which killed her.

The eclipse in that same piece is a nod to Bonnie Tyler's Total Eclipse of the Heart. That music video was so important to me as a kid. It’s so over the top. It’s melodramatic. It’s so ridiculous. It was so gay. Bonnie has doves, roses, angels, and men in speedos getting water thrown at them as they wrestle. All these choir boys fly around with flashing glowing eyes. It’s really homoerotic. It’s an epic drama in itself.

In my work, glowing eyes are stand-ins for otherworldly figures and even horror or sci-fi bodies, which are often metaphors for the queer body. It’s really playing with both offense and defense and then the danger of reflection- both literal and psychological.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!