Published November 17, 2022

So Much Bigger on the Surface of Things: Design & Holism in the Work of Philip Seibel

Throughout the history of high modernism and up to the contemporary moment, the relationship between what we might broadly refer to as design and art has provided a rich ground for both vehement debate and vibrant synergy. Writing in an especially polemical style at the dawn of the 20th century, the Austrian architect Adolf Loos prescribed the idea that aesthetic ornamentation that pleases the senses but offers little by way of functionality ought to be eliminated from the production of buildings, furniture, household tools and utensils, and even culinary recipes. The “urge to ornament” objects, according to Loos, was to be exclusively reserved for an aesthetics of entertainment, for so-called fine art media such as painting and symphonic music.(i) In Loos’s estimation, the practice of design could only reach a maximal degree of efficacy if it disengaged from what he saw as the ostentatious impulses that drive the production of art.

In the following decades, the various schools of thought that compose what is now known as the historical avant-garde took this prohibition on the decorative a step further by using it as a stylistic imperative for any and all aesthetic practices. For movements such as Constructivism, De Stijl, and perhaps most notably the Bauhaus, aesthetic decisions were to be made in such a way that a unity between form and function was established in both designed objects and artworks alike. Even the more radically inclined movements of this period followed the principle of ultimately placing equal levels of value on the respective practices of design and art. Dadaists active in Germany such as George Grosz and John Heartfield scorned what they perceived as the fraudulent pathos of academic painting from bygone centuries. In taking this stance, they effectively called for an acrimonious attitude towards what would otherwise be appreciated as high art. Parallel to the Berlin Dada’s resentment for bourgeois tastes in aesthetics, artists attached to the Futurist movement in Milan regarded automotive design with an almost cultish reverence that found far greater artistry in Alfa Romeo than in Sandro Botticelli.

The flattened relation between design and art forged by the various institutions of the historical avant-garde continues to influence aesthetic discourse to this day, albeit in a far less trenchant fashion. Contemporary museology, for instance, places equal levels of importance on designed objects and artworks as signifiers for a given historical period. As such, one can visit institutions such as New York City’s Museum of Modern Art or The Art Institute of Chicago and view paintings and sculptures in the same building as clocks and couches. Similarly, many art schools are adopting a pedagogical approach that places contemporary art practice in direct relation to the STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), thus forming a disciplinarian network now known as STEAM (the A, of course, standing for Art).

The way we understand the correspondence between design and art today is far more tolerant and accommodating than the examples from the modern age outlined above. The adversarial positioning between the two fields that Loos sponsored now feels antiquated and more than a little condescending, so it’s refreshing that this perspective is now largely acknowledged with a grain of skepticism. And while the vanguard tendency to unite the applied and fine arts has remained in practice, most notably in institutions such as museums and universities, this integration can now thankfully proceed by way of any chosen methodology and not just the strict directives of form and function upheld by movements such as the Bauhaus, or, for that matter, the vindictive and often destructive ideologies championed by both Dadaism and Futurism.

While not as in vogue today as in the 20th century, these theoretical examples from modernity do highlight an important measure for how we understand design-based practices. As noted by the art theorist Boris Groys, the criterion at play here is the “metaphysical opposition” between essence — that is, how an object functions in relation to the given purpose it is determined to fulfill— and appearance — that is, how an object’s aesthetic qualities feel and look and otherwise sensually interact with other objects.(ii) While there was a slight degree of variation depending on the school of thought to which one subscribed, the general modernist principle for handling this opposition was to minimize appearances in order to amplify essences. For Loos, the Bauhaus architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Heartfield, and the Futurists’ de facto leader Filippo Tommaso Marinetti alike, to create an object bereft of frivolous appearances was to create an object that clearly spoke the essential truth of not just its own existence, but of the being qua being of anything whatsoever. What’s blindingly evident now, however, is that intentionally curtailing appearances is still a stylistic method for sensually arranging them. Referring to the hasty association of stripped back prose with literary realism, the author Colin Barrett remarks that such a frugal minimalism is simply “another contrived template, another repertoire of postures” that one can use to abate appearances, but not to erase them entirely.(iii) Given the more open-minded approach to understanding the overlap between art and design that is dominant today, we can now look towards contemporary art to find examples of how the treatment of the essence and appearance dyad has shifted from the high modern status quo. In so doing, we will see that the metaphysical stakes of this relationship have shifted to accommodate lines of philosophical inquiry that are pertinent to life in the 21st century.

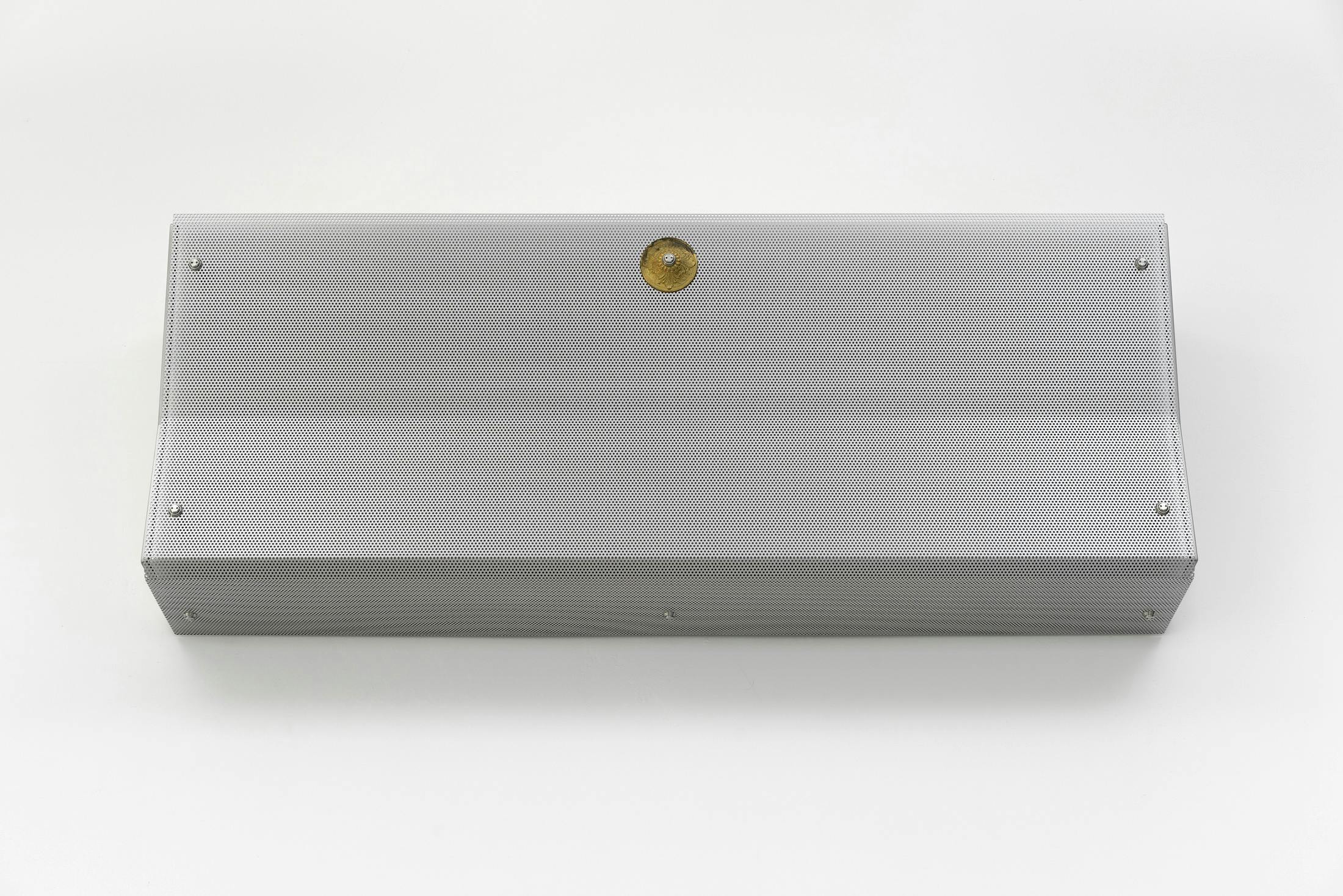

In a quartet of works exhibited by the artist Philip Seibel for his show The Word for World is Forest at the Union Pacific gallery in London, the interaction between essence and appearance plays out in sculptures that resemble air conditioners. These works maintain the proportions of a standard AC unit that you might encounter in an office building, and they’re hung at a level that completes this resemblance. But unlike the HVACs that aesthetically touch you with temperately chilled air, Seibel’s conditioners mark their presence in the room with how luxurious they look. The waves of orange and yellow frozen in the pristinely lacquered finish on Radiator (Morgen) are reminiscent of the streaked golds and cherry-reds seen in early Gibson Les Paul guitars from the 1950s. At the edges of these sunburst panels are strips of dark wood routed into simple but elegant moldings that would look perfectly at home on a piece of Shaker furniture. And nestled in the midst of these finely fabricated panels is a wax relief that delicately depicts a portion of the locks of hair seen in Albrecht Dürer’s drawing Head of an Old Man from 1521.

The appearances of these pieces are modeled after objects from a distinct variety of “historical flotsam” that bobs along the surface of visual culture.(iv) These objects are beyond the horizon of the contemporary moment, but it is actually this age in combination with a certain degree of scarcity that transforms them into a collectible. Such curios have the interesting effect of driving their collectors to almost cartoonish levels of obsession, a phenomenon that is explored at length in the story of a motley cohort of connoisseurs that feverishly chase down celebrity signatures in Zadie Smith’s novel The Autograph Man. Seibel’s sculptures stir some of the same impulses that drive the protagonist Alex-Li Tandem and his colleagues in Smith’s book. This reaction happens even if you’re not an aficionado of the midcentury guitars or the ascetic furniture from which the air conditioners are aesthetically assembled. Upon viewing these artworks, you’re left with this insatiable feeling of yearning, something “warm and dark and infinite” stimulating the pleasure centers of your brain.(v) You long to visually collect more of the same.

Collectibles — be they autographs, guitars, kitchen cabinets, or comic books — achieve this rampant desirability because they are in some sense the legible fragments of a larger narrative corpus. Gather together a sunburst 1959 Les Paul Standard, an original UK pressing of Led Zeppelin’s eponymous debut LP, and a ticket stub for The Who’s exalted performance at the University of Leeds Refectory in 1970, and you begin speaking to the wider narrative of rock n roll music as it emerged in the pubs and college canteens of midcentury England. And this example of a collection is not merely some dry historical accounting: it taps into the chimerical spirit of rock music, the unrestrained angst and rebelliousness that defined not only the sounds but the attitudes of a generation. Collectibles, then, are like the surface effects of stories that function to tell us something that is otherwise difficult to express about ourselves, about culture, about the world at large. They are the reliquary that holds the essence of a grand narrative that cannot itself be told through comprehensible languages.

Seibel’s sculptures, however, with their opulent patina contrived from the aesthetics of luxury hi-fi systems and German Renaissance drawings, don’t exactly add up to one of these mercurial narratives about human existence. As an exhibition, The Word for World is Forest is spatially modeled after the rather drab milieu of a corporate office. The floor of the gallery is covered in the sort of nauseating carpet tiles that one expects to see in a waiting room or a lobby. The strategy of hanging the sculptures at approximately the same level as an actual air conditioner also plays into this architectural affinity with work spaces. If one zooms out from the luscious details in the sculptures and focuses more on the holistic design of the exhibition, one feels as if they are in the offices of a start-up that’s been gutted by a hostile takeover, only the carpet and some HVAC units from a fading enterprise left to appreciate.

If the mouthwatering aesthetics of collectibles make up the appearances of Seibel’s artworks, it is this image of disappearance that is the essence of their display. And while a portrayal of corporate office space is not itself uninteresting, it is not exactly the subject matter of those transcendent grand narratives alluded to above. This isn’t detrimental to the work, however. As the philosopher and sociologist Jean-François Lyotard pointed out as long ago as the late 1970s, we just don’t believe in grand narratives with the same enthusiasm for their alleged credibility that we once might have.(vi) Elusive stories like those of the rock n roll temperament, the univocal identity of a nation and its people, or the unequivocal virtue of a religious deity just ring out now as somewhat hackneyed generalizations. It is actually to the work’s benefit, then,

that Seibel avoids pushing the kind of dogmatism inherent to the grand narrative.

Instead, these artworks offer a different kind of relationship between appearances and essences, a different kind of holism that correlates parts to the whole of which they are a component. Classical gestalt thinking suggests that appearances will transcendentally build upwards into some whole essence that eclipses the sum of all its atomized bits and pieces. As we’ve already seen, this sort of thinking is in full force when memorabilia accumulates to the point that the sum of all the items in a given collection starts resonating with the unspeakable potency of a grand narrative. Seibel’s art offers an inverted form of this arrangement, one in which the whole is but one perforated and minuscule thing in relation to the fecund multiplicity of things that intersect and comprise it. The philosopher Timothy Morton refers to this relationship as subscendence to distinguish it from the more familiar model of transcendental holism offered by gestalt psychology.(vii) In using the subscendent model as a critical framework for looking at Seibel’s sculptures, we see that the luscious surface effects of a piece like Radiator (Mai) or Radiator (Moyland) are abundant in relation to the quite minimal and austere image of office space that is given in the overall exhibition design. The whole in this case is just so much less than the sum of its parts.

Morton’s philosophy frequently ties into concerns from the field of ecological studies, and so it might seem slightly perverse at first to connect The Word for World is Forest with this line of thinking. After all, it’s hard to not automatically read office space as an image of neoliberalism, that corrosive ideology which “envelopes the Earth in misery” with its violent lust for capital and psychopathic indifference for any form of life that isn’t human.(viii) Even the air conditioners themselves might come across as shorthand for those vast quantities of toxic refrigerants that have contributed in a major way to ozone depletion in the last century or so. But these associations are just hangovers from the transcendental holism and grand narratives that emphasize essences and wholes over appearances and parts. Old HVAC units surely do pump obscene amounts of Freon into the planet’s atmosphere, but to give in to reading these systems simply as polluters is a concession that makes a very generic grand narrative out of the multifaceted phenomena that constitute global warming. Similarly, even the offices of multinational corporations are thoroughly subscendent entities. These spaces might indeed host a number of activities that drive the political economy of late capitalism. But they are also the ground for innumerable forms of human and nonhuman being, doing, and thinking, not all of which so readily pledge fealty to neoliberalism and its ethos of accumulation.

Seibel’s practice as an artist seems acutely aware of the binds that constrict our appreciation of aesthetics when we fall in line with a preference for wholes over parts, essences over appearances. The work he produces offers a way out of this foreclosed thinking through an egress that feels particularly compelling to the contemporary moment. Rather than framing the whole as something superior that emerges from the attenuation of appearances, this artist shows us that it is actually a profusion of surfaces in all their sparkling, spectral desirability that starts to show us the essence of something, an essence that is perfectly real but still always less than the sum of all those seductive parts. We live in an age of globalization in which literally any object — designed, aestheticized, commodified, or otherwise — can be perceived as a plethora of superficial interactions with other objects. With this in mind, we might come to understand that Seibel’s approach to navigating the correlation of appearance and essence is a far more interesting way to see and touch and sense the world and the abundance of things that decorate its surface.

(i) Loos, Adolf. “Ornament and Crime.” In Ornament and Crime: Thoughts on Design and Materials, trans. Shaun Whiteside. New York: Penguin Random House, 2019. p. 188.

(ii) Groys, Boris. “The Obligation to Self-Design.” In Going Public, trans. Steven Lindberg. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010. p. 22.

(iii) Barrett, Colin. “The Right Kind of Damage: An Interview with Colin Barrett.” Interview by Jonathan Lee. The Paris Review, 2015.

(iv) Smith, Zadie. The Autograph Man. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2002. p. 114.

(v) Ibid, p. 215.

(vi) Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington, Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

(vii) Morton, Timothy. Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People. London: Verso, 2017.

(viii) Ibid, p. 102.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!