Published January 10, 2023

Self As Multitude: Avery Z Nelson paints the joy and complexity of gender fluidity

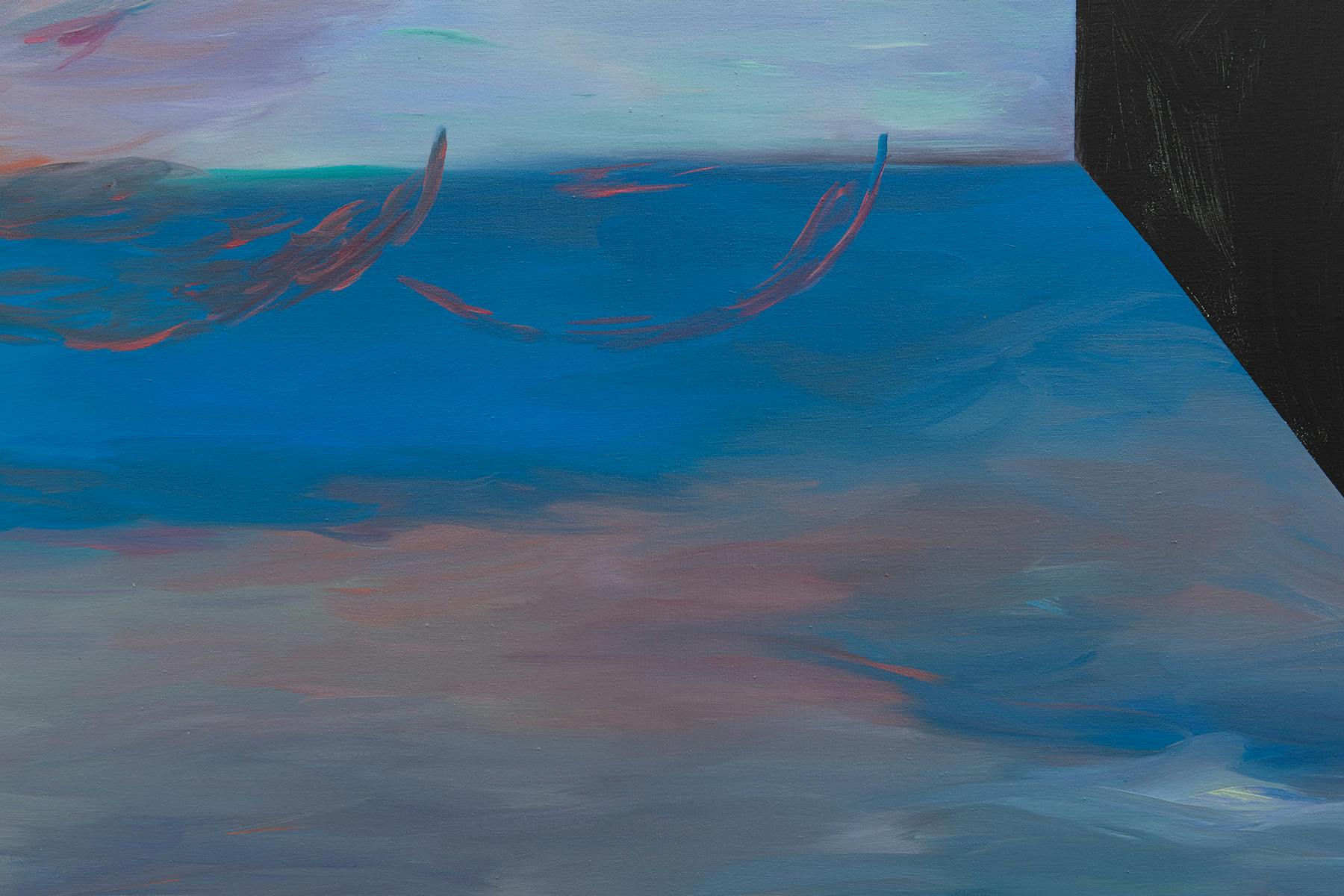

Brooklyn-based artist Avery Z Nelson’s sensuous paintings are visual explorations of becoming trans, embracing a world where categories dissolve and firmly held distinctions are rapturously thrust into ambiguous territory. Nelson uses a distinct painterly vocabulary to revel in the psychological and corporeal components of their own non-binary experience.

After a successful solo show at the upstairs space at Rachel Uffner Gallery in New York City earlier this year, Nelson’s recent solo show at Nogueras Blanchard in Barcelona continues to mine similarly rich conceptual territory.

Avery and I chatted over Zoom about the deep impact of coming out as trans on their practice as a whole, the importance of the human connections they forged through raving, and the profound effect of Covid-related shutdowns on both of these. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Obviously coming out as trans was a big deal. Can you say something about the impact that’s had on your work?

AZN: I can talk about it from two different angles: One as a personal narrative and the second as a sort of formal interest. The personal narrative encompasses how, when I allowed myself to come out as trans, many unnecessary categories which I’d been holding onto dissolved because I developed much more interesting ways of presenting, of being, of organizing self, all of which involved flirting. Embracing the slipperiness of ‘category’ became a very, very exciting thing for me personally. It was also a real, embodied way to link some of my existing intellectual interests in destabilizing categories with coming out as trans, being non-binary and being like “yeah, tits and a dick. That's me. What's next? What does that mean?” And I started raving at the same time.

From everything I know about your practice, those two experiences seem to ‘dance’ with each other within your paintings and within your thinking, which is really fascinating…

AZN: They're very interwoven. I’d say that the formal aspects developed while I was finding my way through this really personal, bodily experience that was always in motion.

I became interested in gesture, memory, and creating psychological spaces in painting. And I started thinking about ways in which I could paint some of that slipperiness by destabilizing what might at first be deemed as two butt cheeks, which then becomes the side of a face, the tip of two fingers, and then an eye.

I ended up developing a kind of mapping system and playing with that. I experienced a process of realization, a sort of dawning of another body part that I’ve always had in a multitude of ways, right? There's no singularity of the dick, but rather the opportunity to flirt and present self as a multitude of bits and pieces – some visible, some invisible, some seen only through a gesture, interaction, a certain type of relationship, or a certain other person. Exploring what it means to be in a body that’s really contingent on relationships and relationality is such an exciting place to paint from, because it's very, very open.

The word ‘fluidity’ really seems to sum that up beautifully. While your works obviously make perfect sense as paintings, the way you’ve just described them has made them almost seem filmic. It sounds as if movement – physical, corporeal, psychological – is so key to your process. You embrace all these elements constantly moving and shifting, but you're also very consciously and specifically embracing that within painting as a medium.

AZN: It’s that tension, right? The painting is inevitably a stagnant object, so how do you create enough movement within it – so it feels as if there’s something shimmering over here so that’s where the viewer’s eye is drawn, but then something else is shimmering down there too.

In your current show at Nogueras Blanchard in Barcelona – I Don’t Want to Live In A World Without Feathers – you've anchored the whole exhibition around the word ‘pitcher’, pulling out these three different definitions and using those as a springboard for a series of three paintings. Can you say a bit more about how that came about?

AZN: I was working on that show relatively quickly. And before that, over the course of making the paintings for my solo show at Rachel Uffner, I had figured out some pretty significant things about how to make a painting for myself relating to poetry and mapping and using a multitude of different signifiers. Whereas the Uffner show consisted of portraits of moments in time, the show at Nogueras Blanchard utilizes this new system to make work using a loose theme of living through and reemerging from the pandemic and returning to the full color spectrum of life now.

Leading up to the show in Barcelona, a student had asked me: “Why do you even bother painting? I don't understand why anyone would do that right now.”

Hmmm, people have been asking that question for quite a while, haven’t they?!

AZN: Right, exactly! And I thought, how do I sincerely answer this question for myself? And my answer was: “I don't want to live in a world without feathers.” I deeply believe in the moments of beauty, the moments of the ornamental, the moments of tenderness, and the moments that shimmer around the edges. I’m also deeply concerned about mass extinction and the environment. Plus, I'm queer, and I find my spaces of community predominantly in queer nightlife where I can dance, flirt, and just be completely ‘feathery’ myself.

I wanted to bring all that together in this body of work. I made Pitcher #1, which depicts this sort of tight claw hand gripping what could be an eye or a ball (though someone in Barcelona told me that it definitely looks most like an olive, and I was like “Cool, it can be an olive too!”).

Then I was going to make a catcher and umpire painting next, but it started to feel a little bit too didactic, and at that point, my attention turned to the pitcher plant, which ties together nature, the outdoors, and a plant that's beautiful but carnivorous. So that line of thinking led to Pitcher #2.

Then, it felt important to me that there was a sensual, ‘toppy’ painting in here too – ‘pitcher’ is also slang for the top in a gay encounter. So I made Pitcher #3 with some loose contour lines suggesting a self-portrait as pitcher.

Those became the three propositions, three nodes for the whole show. From there, I made a series of six smaller paintings that are more like punctuation marks, moments, utterances, or responses to the movement of the three pitcher paintings. Some respond directly to parts of the title or to a specific one of the three larger paintings. The smaller works form a constellation with the three large paintings at its center.

Is there anything or anyone – painters, musicians, filmmakers – that you are really riffing off right now?

AZN: Well, the Jacqueline Humphries show that’s up right now at Greene Naftali – the way she layers paint, the way her work remains abstract while loosely referencing horror in certain ways through stains and gestural references, sometimes there’s a semblance of a face or an emoji or some other signifier. They all figure a ghostly subject without being necessarily figurative, sometimes through what reads as a bloodstain or trace. She often manages to convey something’s complete absence, yet it's still felt. I'm really interested in ways to feel something really strongly without articulating it, so I loved that show.

Then the Wolfgang Tilmans exhibition at MoMA. I obviously love his portrayals of Berlin nightlife, but it’s the intimacy with which he depicts just being with others with absolutely no pretension. He’s just a poet.

I don't want to live in a world without feathers. I deeply believe in the moments of beauty, the moments of the ornamental, the moments of tenderness, and the moments that shimmer around the edges.

We talked about your love of the rave scene a little bit…

AZN: When I started raving in my mid thirties, I found myself in this nightlife community. Mostly what I listen to now is electronic music. One of my favorite DJs, Aurora Halal, played a set at my Rachel Uffner show. It was amazing and packed. Aurora is a phenomenal DJ and producer.

Listening and dancing with others to music in general has given me a visual and embodied image or read of how voices can stack together and unstack and tempos can stack together.

That really comes through in your work in an incredibly positive way. There's a rhythm and a way of breathing and seeing that you only really experience when you're listening to electronic music, I think.

AZN: Being on the dance floor, as I was doing a lot of just before the pandemic hit, being with all these other people, if the music's good, it's very light and everyone's just doing their own thing, they're all dancing as their own completely individual selves, yet at the same time, no one bumps into each other. It’s as if there’s a meditative specificity to everyone’s movement where you can communicate with so much clarity too, just through motion.

It's primal really, isn’t it?

AZN: Yeah, it really taps into something. It comes from this core and then you have this externalized heartbeat through the beat which allows you to so completely dissolve in it, a crowd of moving bodies and yet also being able to express one's own specificity and individuality. That's such a place of everything! It's also a place that's really closely related to creativity.

In your show at Rachel Uffner Gallery, one of its main threads was the way in which this wonderful, fundamentally transformative coming out experience was so bluntly interrupted by Covid shutdowns, specifically in New York City, where you’re based. Can you say a bit more about what that did to your practice?

AZN: The year and a half prior to the pandemic was just so incredibly packed with living, discovery, and connection for me. I was also participating in the Sharpe Walentas studio program when the shutdown first hit.

The first six months were really painful, I’m not one of those people who feel as if there was necessarily a silver lining to that period. There were events outside the studio that definitely made themselves felt in my work indirectly – the BLM protests, for sure.

I think the ways different people experienced lockdowns were entirely dependent not only on where you were in life and your level of privilege, but also your personality and your own level of introversion or extroversion…

AZN: Totally. There was a degree to which I eventually refound myself. I actually lost my studio for the first six months because the Sharpe Walentas building closed completely. Even after that there were serious restrictions on our studio access, which had a massive impact on the extent of our interaction with other participants. Looking back, I do think that some of the first paintings I made for the Rachel Uffner show were directly related to processing the impact of the pandemic; one of the large paintings is titled Reflections There. While making that work, I thought about almost re-cobbling myself back together, like Mr. Potato Head. At the time, I rationalized, “Well, that used to fit there, so I guess I’ll just stick it back in that place for now.” However, those thoughts stand in such stark contrast to the trans fluidity that I was experiencing before. Imagine something quite literally fluid being interrupted. It was actually quite forceful, quite brutal to be cut off like that.

There was one really special rave that happened outside in a swamp four months into the pandemic. I thought: can I go? Can I?! In the end, I went, and that swamp rave really carried me through the next six months.

Although I haven't really connected all the dots from that period, I do know that for me, being buried so deeply in the foundation of self and survival for a period of time led to some pretty big questions – about making a painting and my relationship to painting – that provided some real clarity.

Testudo is always looking for more voices to write with us about the art world. If you’d like to pitch an article, please see our pitch guide for more information!