Published October 14, 2023

William Matheson on Spectrality, the Uncanny, and the Unseen

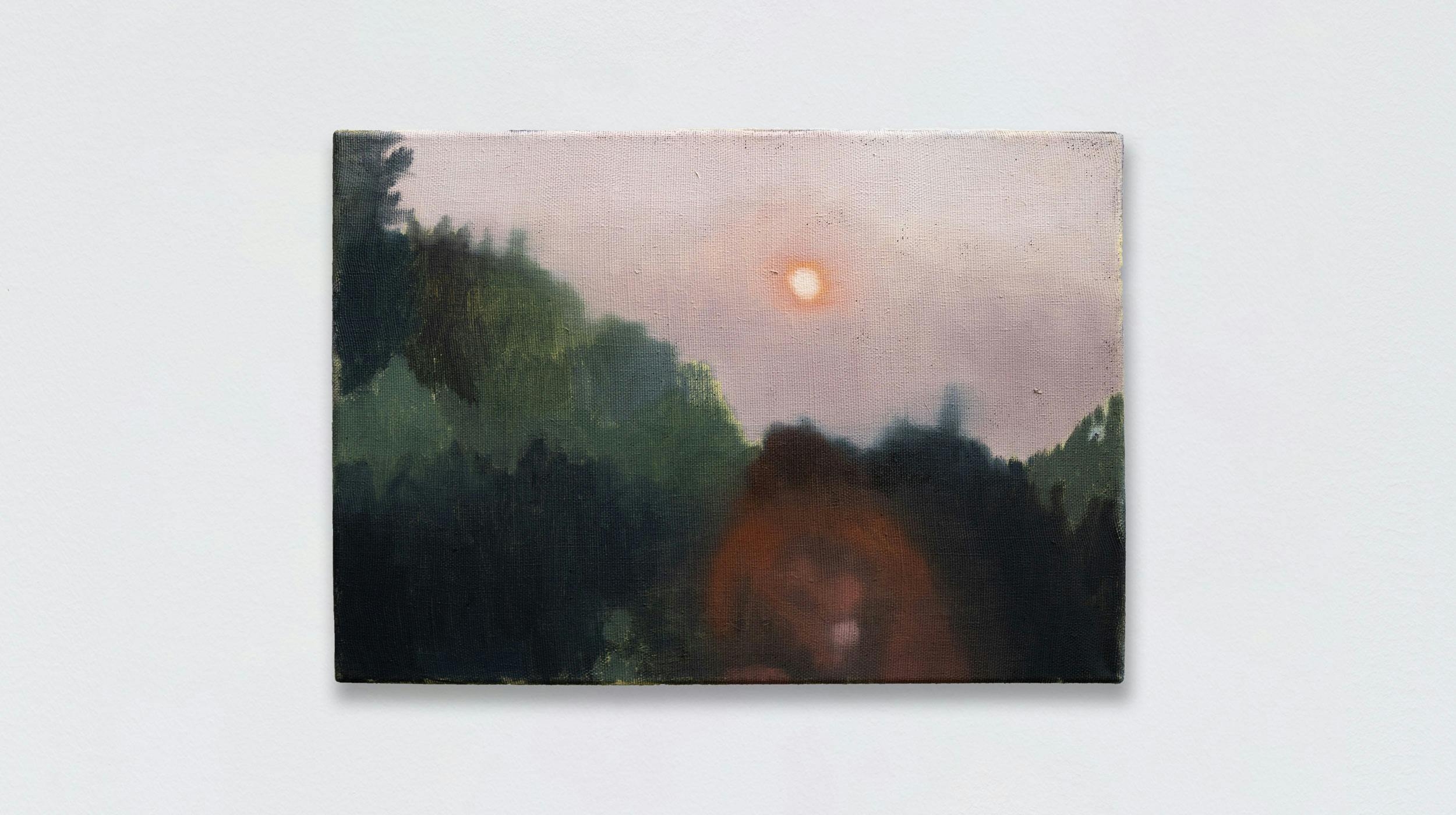

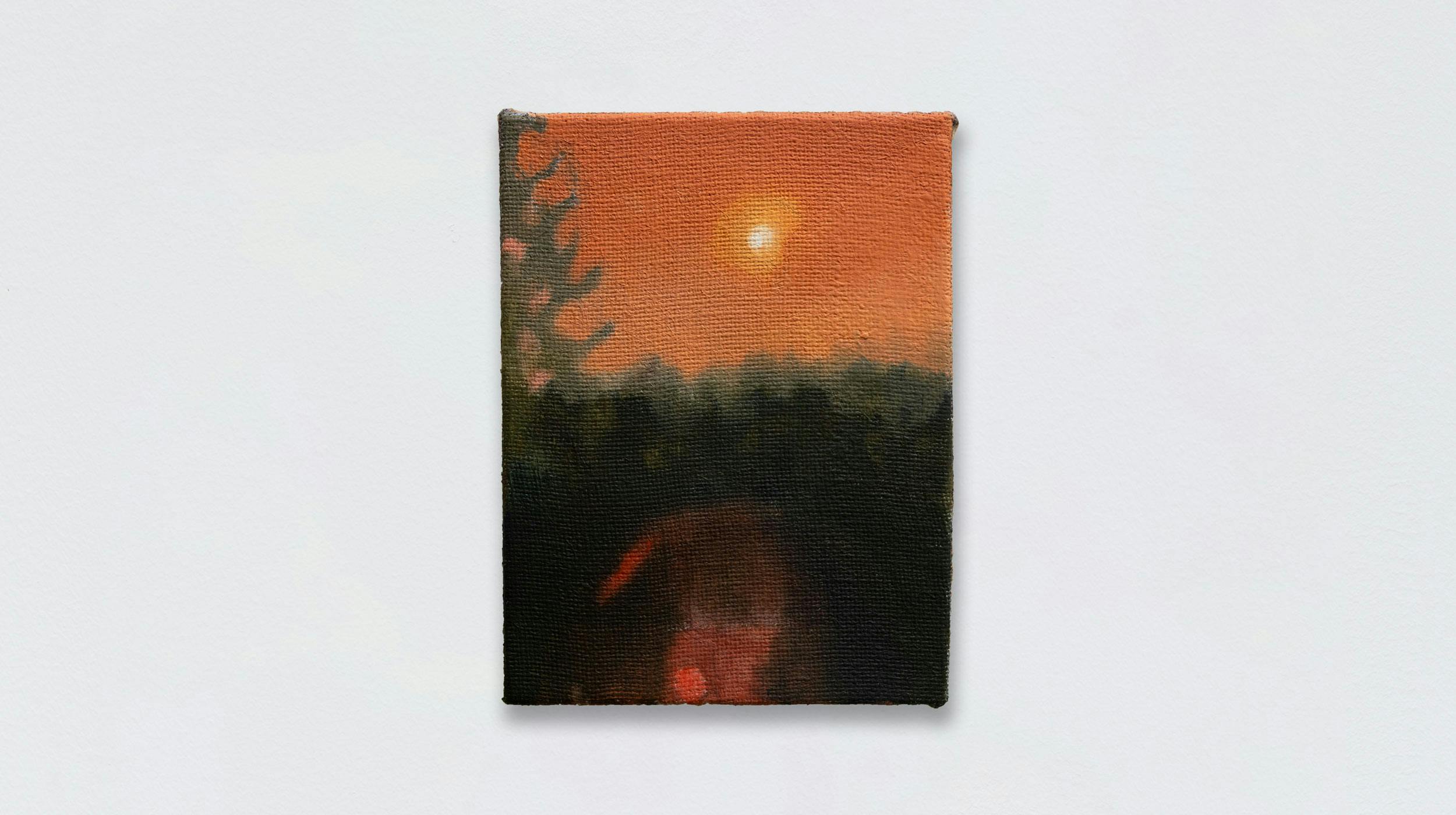

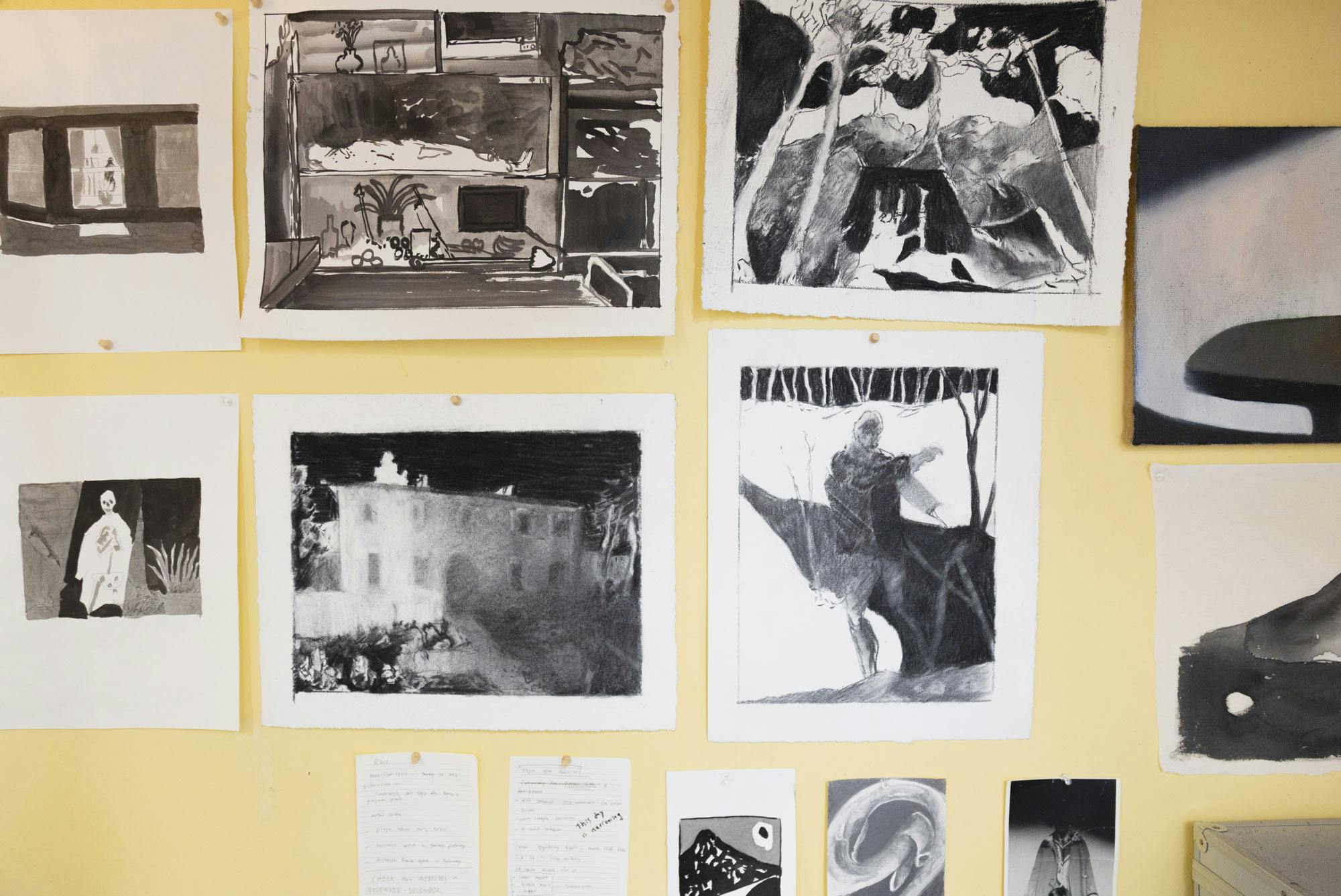

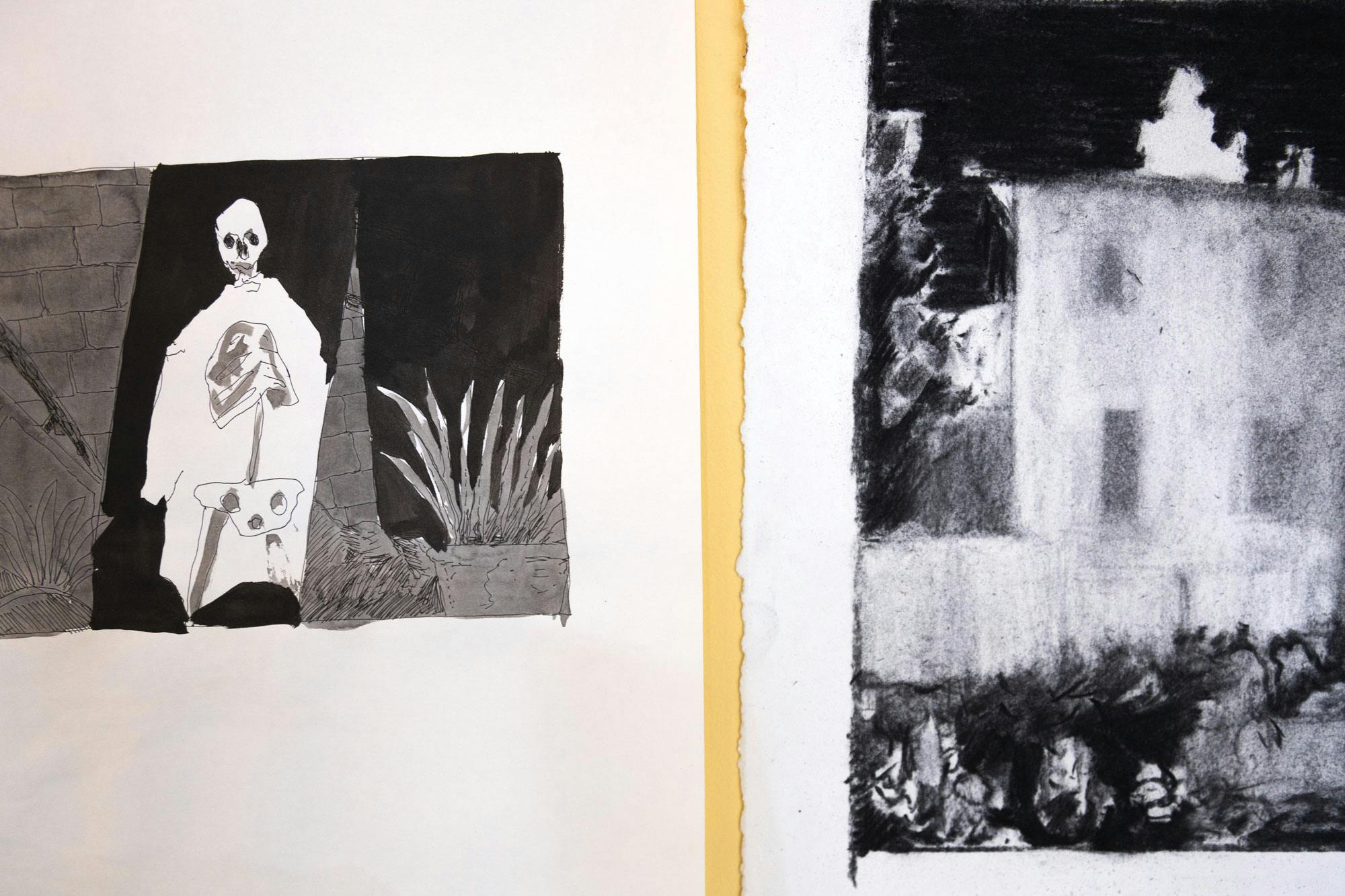

In his highly textured paintings, Portland, OR based artist William Matheson conjures up contemporary gothic moments that inspire the viewer to free-associate. Often at night, Matheson applies thin layers of oil paint with unusual tools such as rags and glass scrapers as well as brushes. He works on jute, panel, and canvas—materials that can have unique bumps and facets. The combination of such techniques and media produces rough surfaces that lend a physicality to each composition. Matheson invites the viewer to take a careful look at each crater, accretion, and gap between marks.

With acidic colors and fields of black pigment, Matheson renders spectral figures and uncanny objects in claustrophobic spaces such as car interiors and his own studio. The artist uses window panes, curtains, shadows, and stacks of ephemera to frame or intersect his scenes. Such compositional devices make these works resemble postwar geometric abstractions; yet Matheson also draws inspiration from the late Gothic and early Renaissance painting canons. The artist materializes the hazy memories, surreal images, and fleeting experiences that haunt ordinary life.

I’d love to start with materials and techniques. Can you describe your process?

WM: I create oil paintings, typically on a fairly small scale with materials such as burlap, jute and linen. These materials have an earthier/rougher quality than traditional canvas. There are small crevices and gaps between the weave of the fibers that create tension between the representational images and the materiality of the surface. I’ve been working with burlap and jute as my primary painting material since late 2021, though I still sometimes use canvas and panels for larger projects.

In terms of process, my paintings are usually informed by intuitive amalgamations of images that I’ve photographed, drawn, collected or found. Often I’ll collage together sources in photoshop and use that as the starting point for a composition. By the time I’m close to completing a painting it will usually have dramatically strayed from the composition of the original source, but I like having that initial reference point tied to the act of collecting and accumulating imagery. I’ve always loved the ability to seamlessly meld disparate threads and make them cohesive. Elements as unrelated as the color of wildfire smoke in summer, a shadow at night, an image from an art history book or a generic image found online, all take equal weight and can be transformed to underscore the themes I work with: spectrality, the unseen, the uncanny and the everyday.

In my painting practice there is a constant mixture of uncertainty and anxiety coupled with ritual and consistency. I love continually showing up, trying to expand the parameters of the work slowly.

Several of the paintings we have on Testudo are from your 2022 exhibition Dissipatio at Nationale in Portland, Oregon. How did that body of work begin?

WM: Disappatio was inspired by this strange existential novella by Guido Morselli called Dissipatio HG. The story revolves around a narrator who intends to commit suicide, fails, and wakes the next day to find that no one else exists. It’s an existential horror story navigating being the last person on earth with no real explanation. It's a very inward novel. There's this interesting tension between the author's inescapable human perspective and then this deep unknown aspect of the expanding natural world. With a lot of the paintings, I was thinking of emptiness and openness and coming to the limits of how much we can understand nature, animals, objects. I read the book in mid 2021, so definitely during the height of the pandemic, which seems fitting. The book has an interesting approach to acknowledging the material otherness of things outside yourself, things you can’t fully reconcile with. I thought that was really interesting and served as a throughline for many of the paintings in the show. A painting like Topiary (Kitchen Window) embodies these themes I think.

Now that we’ve moved a bit out of that very isolating time of the early pandemic, how would you say your work has changed?

WM: A lot of my previous paintings engage with very geometric or enclosed compositions with hard delineated lines, entrapping figures in really rudimentary forms of staging, which intensified during the pandemic with works like An Ending or Illness Icon (2). I really like the idea that most of the paintings that I make exist as really simple, tense, little black box stages. I’ve noticed in some of the more recent paintings there's more of a usage of natural space and less hard edges. There’s still a tension between natural objects, figures, and things that anthropomorphize, but it might not be as hard edge. That really tight, harsh geometry might have been most prominent during the pandemic. Things have become a bit more open and natural since then.

And you’ve mentioned doing a lot of work at night; how does that influence the work?

WM: Most of the free time I have is at night, and I’ve always loved how solitary but also generative night is. I think this nocturnality reinforces my approach to the themes I work with: spectrality, the uncanny, and the unseen. I feel very lucky that my current studio is a small building in the back of our backyard. At night it acts as a beacon because it's brightly fluorescently lit. When I’m working inside the studio, I can't see outside at all. There's this interesting tension. I know what's outside of course– the backyard which I engage with all the time–but also during that time on some deeper level, I don't. I’m very interested in these kinds of spaces where you exist with the unseen.

For my day job, I work as an operations coordinator for an EV charging company in Portland. The position’s fully remote, which is great. I often work on the desktop inside my studio. Both consciously and subconsciously, it allows me to engage with my paintings, and spend time with the work and explore possibilities. I spend a lot of time in the studio where I’m not actively working, but still looking. I like having time to ruminate on everything.

In the past I’ve worked jobs where you’re expected to show up in the office for eight hours, and that can be challenging in conjunction with trying to maintain a studio practice. There definitely was a tension between the expectations of nine-to-five work and then trying to manage time for creative work at the end of the day. I feel that right now, even though my job doesn’t directly pertain to my creative work, it helps support and nurture it in these interesting ways, both directly in terms of finance and also in terms of time. I also like having a clean separation: this is my job, this is what I do during the day, and then the creative work is separate, independent, and exists at night. I’ve come to enjoy that.

What else do you do when you’re not in the studio or making art?

WM: My wife and I have a one year old daughter, so we spend most of our free time with her. It's been amazing–she loves books, nature and animals, and with each month that goes by you just see more and more complexity and curiosity. We’re getting close to the point where she’ll start drawing/playing with art supplies, which I’m obviously very excited about. I’m also an avid runner and I run around 30 miles a week. I find it calming and meditative, and often use it as space to think through paintings.

How has becoming a parent impacted your work?

WM: I think being a parent has quietly, but meaningfully, changed the way I approach image making, though I’m still in the process of articulating this.

Initially, during the newborn stage I stopped painting for a few months, but I think we've found good ways to balance that now. Our daughter is a good sleeper, which is amazing. I think that's the big thing that has afforded me space to keep making work consistently.

In terms of the images that I'm making, I have this nascent feeling that a lot of them are informed by being a parent, by both how profoundly beautiful and hopeful it is, coupled with this deep worry about the future. About climate change and everything seeming to accelerate. I think that feeling existed in the work before, but it feels different now; this duality between hope and anxiety seems intensified.

We’re starting to see more direct images of wildfires in some of your newer paintings. Tell me more about what you’re exploring there.

WM: I’ve slowly been incorporating the experience of living in the Pacific Northwest more into my work. For half the year there are wildfires. The smoke during the summer is an incredibly intense experience. It feels like a presence or specter that’s insidious but it also strangely and seamlessly becomes a part of the background. I find myself returning again and again to icons and colors that deal with this experience.

It’s interesting to think about these images of climate change becoming more visible and regular. We had a few days over the summer where smoke from the Canadian Wildfires floated down, and it really was a scene that people living in New York City are not accustomed to seeing…

WM: Yeah, I saw those images. It's surreal to watch these images become common and ubiquitous, because it's the kind of thing that would have existed in a cheap apocalyptic movie 15 years ago and seemed impossible. That's something I think about with painting and visual image making - acknowledging that it is and always will be an incredibly unsettling, irreconcilable image. You can never fully accept seeing the sun glowing white, irradiated in a deep red-orange sky.

I've always found horror movies interesting–especially a lot of the practical effects and utilization of staging and shadows and darkness. Those have been sources and inspiration for a lot of my paintings, especially with a work like Eidolon, which directly references horror iconography. But on a more basic level something that I really like about the idea of spectrality is that it’s so present now in the everyday. So something as simple as sunlight filtered through smoky air or the outline of a shadow can come to represent what's so haunted about our age.

Are there particular artists that have influenced your work?

WM: I love late gothic painting into the early Renaissance - right up until three point perspective became ubiquitous and refined. Artists like Duccio, Sassetta and the Master of the Osservanza. Their usage of pictorial space is so peculiar and uncanny. There is, for lack of a better word, a dreamlike quality to the imagery and this deep tension in how figures exist in space–as if the environment in the canvas or panel exists in a state of understated impossibility that the figure both resists and is also enveloped by. I think about this sort of simple spatial tension frequently when creating work. Several of the paintings on Testudo were directly inspired by the use of space and color palettes from the Sienese renaissance, including Child Rider and Topiary.

For current painters I’m looking at Andrew Cranston, Miriam Cahn, Merlin James, Anthony Cudahy, Louise Giovanelli, Anders Davidsen, Jessie Homer French, Micahel Armitage and Guimi You.

Do you have any exhibitions coming up? Where can we find you and your work?

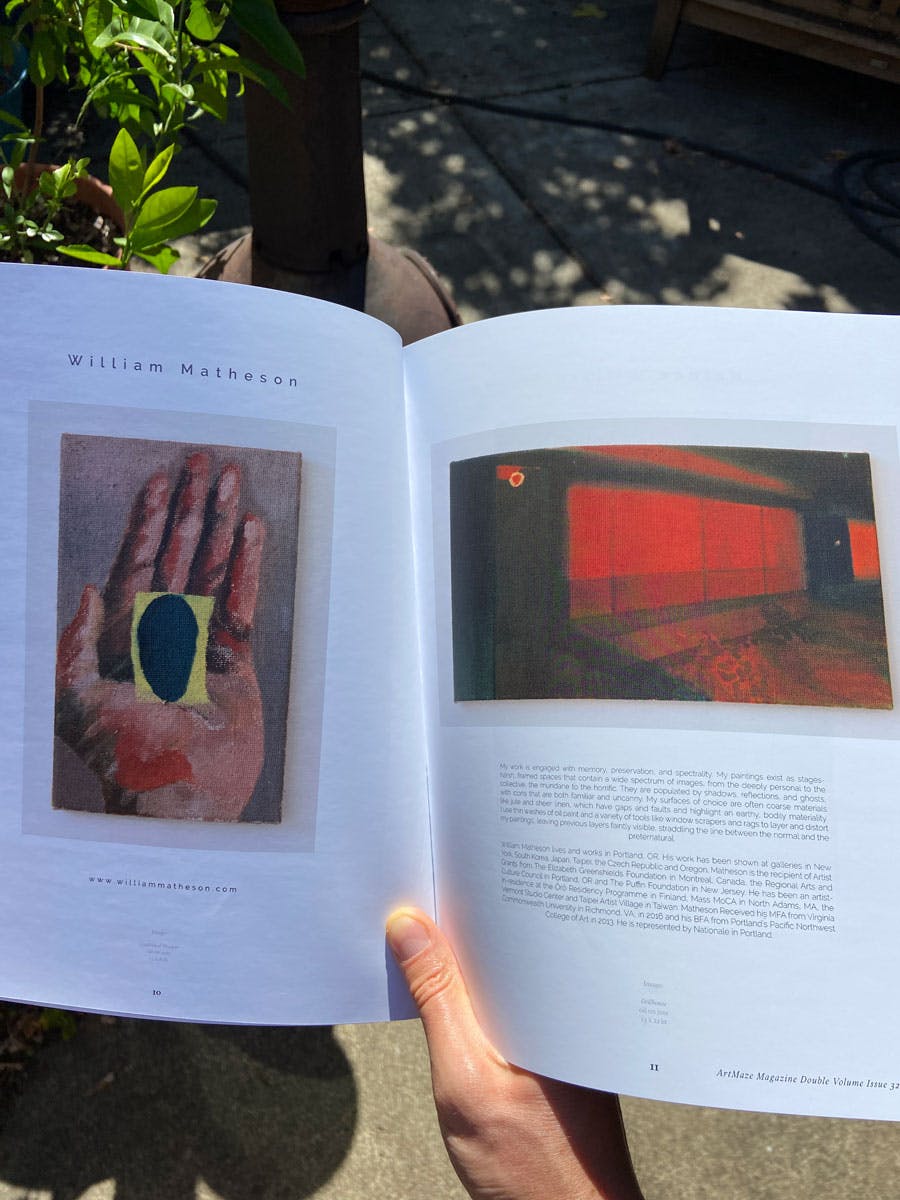

WM: I’m featured in the very recent issue 32-33 of ArtMaze magazine. They’ve consistently shown many of my favorite painters, so it’s very exciting to be included alongside many other emerging artists. I also have a gallery I work with in Portland, OR, Nationale, where I'm planning on exhibiting new paintings in Spring of 2024.